Phonemes are the smallest units of sound in spoken language — the /c/ in cat, the /sh/ in shoe. Being able to hear, notice, and play with these sounds is called phonemic awareness. Research shows that children who can break words into phonemes and blend them back together usually find reading and spelling easier.

But here’s where it gets complicated: while a certain level of phonemic awareness is essential, years of studies reveal that advanced phonemic drills alone don’t guarantee fluent reading. In fact, overemphasizing phoneme manipulation may put the cart before the horse.

In this article, we’ll explore the difference between phonological and phonemic awareness, look at how these skills connect to reading, unpack what research really says about phonemic awareness training, and explain why Edublox believes phonemes are only one piece of the literacy puzzle.

Table of contents:

- Phonological vs. phonemic awareness

- What is phonemic awareness?

- Assessing phonemic awareness skills

- Phonemic awareness and reading

- What is phonemic awareness training?

- Research studies show mixed results

- Conclusion

Phonological vs. phonemic awareness

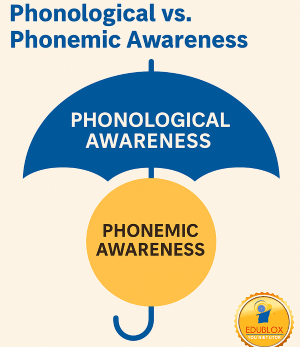

Phonological awareness is the umbrella skill. It’s the ability to notice and work with the sound structure of spoken language — from big chunks like rhymes to the tiniest sounds.

Phonemic awareness is one specific skill under that umbrella. It focuses only on the smallest units of sound: phonemes.

Think of it this way:

- Phonological awareness = broad listening skills

- hearing rhymes (cat / hat)

- noticing alliteration (big brown bear)

- clapping out syllables (ta-ble, com-put-er)

- identifying smaller sound parts within words

- Phonemic awareness = the most advanced part of phonological awareness

- isolating sounds (What’s the first sound in paste? → /p/)

- blending sounds (/s/ /u/ /n/ → sun)

- segmenting sounds (ship → /sh/ /i/ /p/)

Kilpatrick (2016) explains it well: easier phonological skills create the foundation, but phonemic awareness is the capstone. A child might enjoy rhyming games or clapping syllables, yet still struggle with phonemic awareness — which is why many children with reading difficulties can rhyme or recognize syllables but cannot segment or blend phonemes.

What is phonemic awareness?

The word phoneme comes from the Greek phonos, meaning “sound.” A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound in a spoken word.

Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear, notice, and manipulate these sounds — without looking at print.

Letters vs. sounds

It’s important to remember:

- Phonemes are oral → the sounds we say and hear.

- Letters are written → the symbols we use to represent those sounds.

Sometimes they line up neatly:

- tap → three letters, three phonemes: /t/ – /a/ – /p/.

But often they don’t:

- bake → four letters, three phonemes: /b/ – /ā/ – /k/.

- shoe → four letters, two phonemes: /sh/ – /oo/.

This mismatch is why learning to read English can be tricky.

Why it matters

Phonemic awareness lets children do things like:

- Break a word into its sounds (ship → /sh/ – /i/ – /p/).

- Blend sounds to make a word (/s/ – /u/ – /n/ → sun).

- Change one sound to make a new word (cat → change /k/ to /h/ → hat).

These oral skills form the bridge between spoken language and written words. Without them, learning to decode print becomes much harder.

Assessing phonemic awareness skills

Researchers and teachers often use short oral tasks to see how well a child can hear and work with sounds in words. These same tasks can also be used for practice (Tønnessen & Uppstad, 2015):

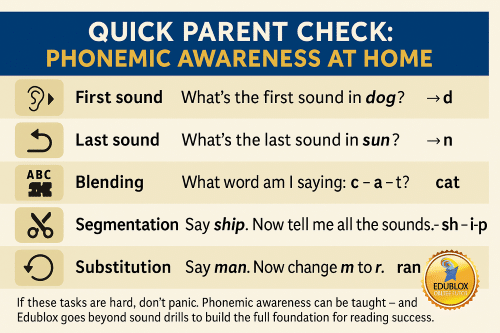

The six core skills

- Phoneme isolation – hearing one sound in a word.

“What’s the first sound in paste?” → /p/ - Phoneme identity – spotting the same sound across different words.

“Which sound do you hear in bike, boy, bell?” → /b/ - Phoneme categorization – finding the word that doesn’t belong.

“Which word is different: bus, bun, rug?” → rug - Phoneme blending – putting sounds together to make a word.

/s/ – /k/ – /oo/ – /l/ → school - Phoneme segmentation – breaking a word into its individual sounds.

“Tell me all the sounds in ship.” → /sh/ – /i/ – /p/ - Phoneme deletion – saying a word with one sound removed.

“Say smile without the /s/.” → mile

Why these skills can be hard

Tasks like these demand a lot of focus and abstract thinking. That’s why children with reading difficulties may struggle, even if they can do simpler sound activities like clapping syllables or noticing rhymes.

Phonemic awareness and reading

Two skills stand out as especially important for early reading: segmenting words into sounds and blending sounds together. These abilities are strongly linked to decoding (sounding out unfamiliar words) and reading fluency.

- Decoding is breaking a written word into letters or letter groups, matching them to sounds, and blending the sounds back together.

- Fluency is reading quickly, accurately, and with expression.

The ability to segment and blend phonemes is considered especially critical for developing these reading skills, and even predicts later reading ability (Taylor, 1998; Moustafa, 2001).

Marilyn Jager Adams called phonemic awareness the “most important core and causal factor separating normal and disabled readers” (Adams, 1990, pp. 304–305). Kilpatrick (2016) likewise argues that phonological awareness training can prevent and correct reading difficulties (p. 13).

Together, these views shaped the phonological deficit theory, which became the leading explanation for dyslexia and reading difficulties. According to this theory, poor phonological skills—especially at the phoneme level—cause children to struggle with reading and spelling. Research in the U.K. and U.S. supported this view:

- Children with strong phonological skills generally become good readers and spellers.

- Children with weak phonological skills tend to progress poorly, and many are later classified as dyslexic (Goswami, 1999).

What is phonemic awareness training?

Phonemic awareness training teaches children to notice and manipulate phonemes in spoken words. Early activities focus on “basic” skills such as:

- Segmentation: “Tell me each sound you hear in cat.” (/k/ – /a/ – /t/)

- Blending: “What word do these sounds make: /k/ – /a/ – /t/?” → cat

Some scholars also promote “advanced” phonemic awareness, which goes further:

- Phoneme deletion: “Say cat without /k/.” → at

- Phoneme substitution: “Say cat. Now change /k/ to /p/.” → pat

- Medial and blend changes: “Say bat. Now change /a/ to /i/.” → bit; or “Say stop. Now change /t/ to /l/.” → slop

Advocates present these advanced perspectives as evidence-based and consistent with the Science of Reading, and are sometimes used in U.S. state policies for reading instruction (Clemens et al., 2021).

📌 Edublox’s view on phonemic awareness training

Phonemic awareness is important — but it is not a silver bullet.

Yes: Children need some ability to segment and blend sounds to get started with reading.

No: Endless drills on deleting or swapping sounds (advanced phonemic awareness) have not been shown to produce better readers.

At Edublox, we support the basics, but we know reading success depends on much more: attention, sequencing, processing, memory, language skills, and real practice with print. That’s why our programs go beyond sound games to strengthen the underlying cognitive skills children need for lasting literacy.

Research studies show mixed results

Do phonemic awareness lessons actually improve reading? The research isn’t unanimous.

Early advantage, but short-lived

Reading and Van Deuren (2007) compared two groups of first graders: one had received phonemic awareness instruction in kindergarten, the other had not. At the start of first grade, the early-training group did better on phoneme segmentation and had fewer children at risk for reading difficulties. By midyear, however, the gap disappeared — both groups were reading at similar levels. Their conclusion: phonemic awareness skills can be picked up quickly, and extra training in kindergarten does not necessarily produce long-term advantages.

Training alone may not help low readers

Weiner (1994) studied 79 first graders in three different phonemic training approaches (“skill and drill,” training plus decoding, training plus decoding and reading) and a control group. Results showed no significant differences on most measures of phonemic awareness or reading, except for a slight edge in segmentation. For struggling readers, even training tied to decoding and reading did not consistently translate into stronger reading outcomes.

Correlation vs. causation

Moustafa (2001) warned that while phonemic awareness and reading are highly correlated, this does not prove causation — just as hospitals don’t cause illness, though the two go hand in hand. Other reviews have echoed this caution:

“Bus & van IJzendoorn (1999) found that phonemic awareness in kindergarten accounts for 0.6 % of the total variance in reading achievement in the later primary years. Troia (1999) reviewed 39 phonemic awareness training studies and found no evidence to support phonemic awareness training in classroom instruction. Krashen (1990a, 1999b) conducted similar reviews and had similar findings. Taylor (1998) points out that phonemic awareness research is based on the false assumption that children’s early cognitive functions work from abstract exercises to meaningful activity, rather than vice-versa, as in other learning.”

Tønnessen and Uppstad (2015) further noted that some excellent readers perform poorly on phoneme isolation, identity, categorization, blending, segmentation, and deletion. This raises doubts about how necessary these tasks really are.

There is also evidence that phoneme awareness may develop as a consequence of exposure to reading and writing. Studies of adult illiterates and readers of non-alphabetic scripts show that without print, phonemic awareness remains limited — suggesting that learning to read may drive phonemic awareness, not just the reverse.

The advanced training debate

Recent scholars argue that pushing children into ever-more complex phonemic manipulations is a cart-before-the-horse approach. Brown et al. (2021) and Shanahan (2021) note that these recommendations lack evidence and may distract from what actually builds reading: working with print, vocabulary, meaning, and comprehension.

Conclusion

Some level of phonemic awareness — especially the ability to segment and blend three- to four-sound words — is clearly important for beginning reading instruction (O’Connor, 2011). But research shows that pushing children into increasingly complex phoneme manipulations does not reliably improve reading outcomes. In fact, phonemic awareness may develop more as a result of learning to read and write than as a precondition for it.

Edublox strongly supports the findings of the National Reading Panel (2000) and What Works Clearinghouse (Foorman et al., 2016): young children benefit from phonemic awareness instruction to help them connect sounds with print. However, there is no evidence that mastering advanced phonemic skills leads to stronger reading, and newer research suggests that reading difficulties like dyslexia cannot be explained by a single phonological deficit (Peterson & Pennington, 2012; Pennington, 2006).

Phonemic awareness is necessary, but not sufficient. Reading success depends on a wider foundation — memory, attention, sequencing, phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension. That’s why at Edublox, we integrate sound awareness with the broader cognitive skills children need for lasting literacy.

👉 If your child is struggling with reading, book a free consultation to explore how Edublox can help build the full foundation for success.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning disabilities. We support families in the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

References for Phonemic Awareness: What It Is, Its Role in Reading, Training:

- Adams, M. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Brown, K. J., Patrick, K. C., Fields, M. K., & Craig, G. T. (2021). Phonological awareness materials in Utah kindergartens: A case study in the science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S249–S272.

- Clemens, N., Solari, E., Kearns, D. M., Fien, H., Nelson, N. J., Stelega, M., … & Hoeft, F. (2021). They say you can do phonemic awareness instruction “in the dark”, but should you? A critical evaluation of the trend toward advanced phonemic awareness training. PsyArXiv Preprints

- Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C. A., Dimino, J., … & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade. Educator’s Practice Guide. What Works Clearinghouse, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Goswami, U. (1999). Integrating orthographic and phonological knowledge as reading develops: Onsets, rimes, and analogies in children’s reading. In R. M. Klein & P. McMullen (Eds.). Converging methods for understanding reading and dyslexia (pp. 57-75). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Kilpatrick, D. A. (2016). Equipped for reading success. Syracuse, NY: Casey & Kirsch Publishers.

- Moustafa, M. (2001). Contemporary reading instruction. In T. Loveless (Ed.), The great curriculum debate: How should we teach reading and math? (pp. 247-267). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

- O’Connor, R. E. (2011). Phoneme awareness and the alphabetic principle. In R. E. O’Connor & P. Vadasy (Eds.), Handbook of reading interventions (pp. 9-26). Guilford Press.

- Pennington, B. F. (2006). From single to multiple deficit models of developmental disorders. Cognition, 101(2), 385-413.

- Peterson, R. L., & Pennington, B. F. (2012). Developmental dyslexia. The Lancet, 379(9830), 1997–2007.

- Reading, S., & Van Deuren, D. (2007). Phonemic awareness: When and how much to teach? Reading Research and Instruction, 46(3), 267–285.

- Shanahan, T. (2021). RIP to advanced phonemic awareness. https://tinyurl.com/ycxf3dsn.

- Taylor, D. (1998). Beginning to read and the spin doctors of science. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

- Tønnessen, F. E., & Uppstad, P. H. (2015). Can we read letters? Reflections on fundamental issues in reading and dyslexia research. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Weiner, S. (1994). Effects of phonemic awareness training on low- and middle-achieving first graders’ phonemic awareness and reading ability. Journal of Reading Behavior, 26(3), 277–300.

Phonemic Awareness: What It Is, Its Role in Reading, Training was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational and reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

Edublox is proud to be a member of the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), a leading organization dedicated to evidence-based research and advocacy for individuals with dyslexia and related learning difficulties.