For decades, dyslexia was seen as a lifelong limitation. But discoveries in neuroplasticity have rewritten that story. The brain is not fixed — it can adapt, reorganize, and grow in response to learning. This article explores how the science of brain plasticity, once dismissed, now offers real hope. From early pioneers like James Hinshelwood to cutting-edge MRI studies, we trace the evolution of understanding and explain why cognitive training, when paired with the right interventions, can help rewire the dyslexic brain.

We specialize in helping children overcome the symptoms of dyslexia. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

.

Table of contents:

- What is neuroplasticity?

- The brain cannot change

- Brain plasticity is discovered

- How the nervous system works

- The brains of people with dyslexia

- Reduced plasticity in the dyslexic brain

- What does it mean?

What is neuroplasticity?

Neuroplasticity, or brain plasticity, refers to the brain’s remarkable ability to change in response to learning and is one of the most extraordinary discoveries of the 20th century. It proved that our brains are not fixed after childhood.

New brain cells are constantly being born and dying, new connections form, and the internal structures of existing synapses change. When a person becomes skilled in a specific area, the brain regions involved in that skill grow. Neuroplasticity enables brain cells to adapt to injury and disease and to change their activity in response to new situations or environmental shifts.

The brain cannot change

For centuries, scientists believed the brain could not change, let alone improve. If something was “wrong” with the brain, it was considered permanent. Experts claimed that we were born with all the brain cells we would ever have and that lost cells could not be replaced.

According to Doidge (2007), this belief had three main origins:

- Brain-damaged patients rarely made full recoveries.

- The microscopic activity of the living brain couldn’t be observed.

- The brain was compared to a magnificent but rigid machine — powerful but unchangeable.

And unlike machines, human brains do grow and adapt.

We now know that the brain can reorganize itself, changing both its structure and function. When certain regions fail, other parts can sometimes compensate. And this plasticity is not limited to childhood — it continues from the cradle to the grave.

The word neuro refers to neurons, the brain’s nerve cells. Plastic means malleable or modifiable. Initially, even scientists were reluctant to use the term “neuroplasticity,” and those who did were often ridiculed. Yet they persisted — and over time, they overturned the belief in a static, unchangeable brain.

One early pioneer was James Hinshelwood, considered the father of dyslexia research. In his 1917 book Congenital Word-Blindness, he explicitly referred to brain plasticity. Hinshelwood believed dyslexia (then called word-blindness) could be treated through personal, systematic instruction.

He held out hope not only for children with developmental dyslexia but also for individuals who acquired dyslexia after brain injury or illness. He believed the brain could be reeducated — that other brain regions could take over the function of damaged ones — and documented case studies in which this occurred.

Sadly, his view was largely ignored for decades. Throughout the 20th century, the belief that the brain was fixed persisted — leaving little hope for people with dyslexia (Keshav, 2018).

Brain plasticity is discovered

A major breakthrough came in 1998 when researchers published a study showing that the adult human brain can generate new brain cells (Eriksson et al., 1998). This finding challenged the long-held belief that the brain was a fixed system incapable of growth or regeneration.

Further research confirmed what early pioneers like Hinshelwood had suspected: the brain is flexible and adaptable — in other words, plastic.

One of the most famous demonstrations of this came from a series of studies on London taxi drivers. In a 2000 experiment, neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire and her team compared the brains of London taxi drivers to those of non-taxi drivers (Maguire et al., 2000). Later, in 2006, they extended the comparison to London bus drivers (Maguire et al., 2006).

The inspiration came from the animal kingdom. Certain birds and mammals — like scrub jays and squirrels — hide food and later retrieve it. This ability depends on precise spatial memory. Researchers found that in these animals, the hippocampus (a brain region essential for long-term memory and navigation) was larger than in animals without these skills. In some species, the hippocampus even expanded seasonally, depending on when spatial ability was most needed.

Maguire wondered if the same plasticity might be found in humans who rely heavily on spatial memory. London cab drivers must memorize around 25,000 streets and countless landmarks before they can earn a license. Her studies revealed that these drivers had enlarged posterior hippocampi — larger even than bus drivers, who follow fixed routes and don’t require the same level of spatial memory.

Interestingly, the more years of navigation experience a taxi driver had, the greater their hippocampal gray matter volume.

Other studies have shown similar findings across different types of expertise:

- Musicians develop greater gray matter in regions tied to auditory and motor processing (Gaser & Schlaug, 2003; Sluming et al., 2002).

- Bilinguals show structural differences in language-related areas (Mechelli et al., 2004).

- Jugglers exhibit changes in brain regions linked to motion tracking and coordination (Draganski et al., 2004).

- Foot painters develop “hand-like” neural maps of their toes (Dempsey-Jones et al., 2019).

- Illiterate adults learning to read show changes not only in the cortex but also in deep brain structures like the thalamus and brainstem (Skeide et al., 2016).

The implication is clear: our brains change in response to training, learning, and environmental demands.

A century after Hinshelwood’s hopeful predictions, neuroscience finally caught up. We now know that healthy parts of the brain can be trained to take over damaged areas — an idea he described in 1917 and one that modern research now supports (Kadosh & Walsh, 2006; Nudo, 2013).

How the nervous system works

Neurons, or nerve cells, are the fundamental units of the brain and nervous system. They process sensory input, send commands to muscles, and transmit electrical signals that enable everything from thought to movement.

The nervous system is divided into two main parts:

- The central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain and spinal cord. It acts as the control center for the entire nervous system and was long believed to lack plasticity.

- The peripheral nervous system (PNS) carries messages between the CNS and the rest of the body — from sensory receptors to the brain and from the brain to muscles and glands. Unlike the CNS, the PNS has long been known to be plastic. For example, if a nerve in the hand is severed, it can often regenerate and heal itself.

.

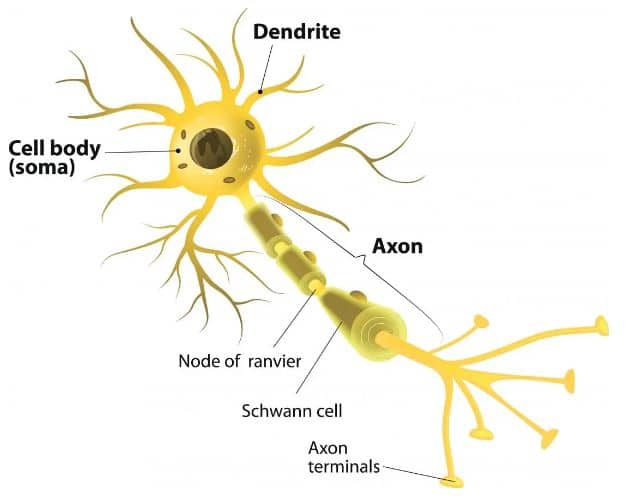

Each nerve cell has three primary parts:

- Dendrites receive input from other neurons (like tree branches reaching out).

- The cell body (or soma) contains the nucleus and keeps the cell alive.

- The axon, a long, cable-like structure that transmits electrical signals to neighboring neurons. Axons can vary in length — some are microscopic, while others stretch from the spine to the toes — and they send signals at speeds ranging from 2 to 200 miles per hour.

A neuron receives two types of signals from surrounding cells:

- Excitatory signals, which increase the likelihood that it will fire.

- Inhibitory signals, which reduce the likelihood of firing.

When enough excitatory input accumulates, the neuron sends its own electrical signal down the axon. This signal triggers the release of a chemical messenger — a neurotransmitter — across the synapse, the small gap between neurons. The neurotransmitter then binds to receptors on the next neuron’s dendrites, continuing the process.

When we say that neurons “rewire” themselves, we mean that these synapses strengthen or weaken over time. Stronger connections improve communication between neurons; weaker ones can fade away. This is the biological foundation of learning and memory — and the heart of neuroplasticity.

The brains of people with dyslexia

As early as the late 19th century, researchers like Berlin (Opp, 1994), Morgan (1896), and Hinshelwood (1895) linked dyslexia to brain function and brain injury. Later, in the 1980s and 90s, autopsy studies of individuals with documented dyslexia appeared to support these early observations.

As imaging technology advanced, neuroscience began to illuminate how the brains of individuals with dyslexia differ from those of typical readers. Structural and functional differences have since been widely documented.

One of the most consistent findings concerns the left occipitotemporal cortex, particularly the visual word form area (VWFA) — a region critical for reading (Glezer et al., 2016). This area quickly groups letters into recognizable word units in skilled readers, allowing for fluent reading without letter-by-letter decoding.

Another key region is the left inferior parietal lobe, which assists in analyzing words, converting letters into sounds, and integrating phonology with meaning.

In students with dyslexia, both the VWFA and the parietal lobe may function differently or less efficiently. When the VWFA is underactive, children may struggle with reading fluency. When the parietal lobe is affected, they may find it difficult to sound out unfamiliar words, relying instead on guessing or memorization.

Some studies also show that these challenges can lead to overactivation in other areas of the reading network — a kind of neurological workaround.

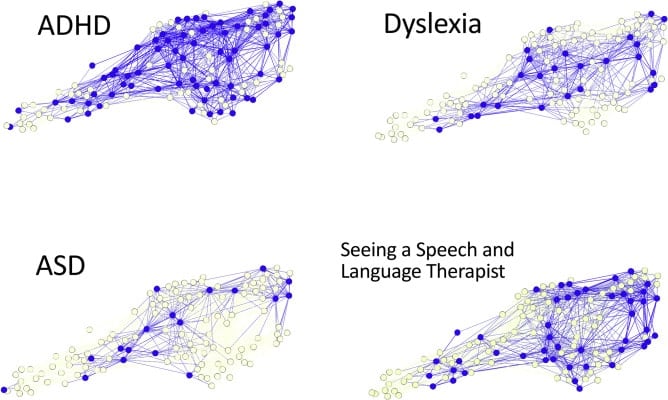

However, not all research agrees on specific brain-based “causes” of dyslexia. A study by the University of Cambridge (Siugzdaite et al., 2020) found no single brain region responsible for dyslexia or other learning difficulties. Instead, they discovered that children’s brains are organized around hubs, similar to transportation or social networks. Children with well-connected hubs had no learning challenges, while those with poorly connected hubs experienced broad cognitive difficulties.

In addition, some researchers suggest that brain differences observed in dyslexia may be the result of reading experiences — not necessarily the cause. For example, Krafnick et al. (2014) found that structural brain differences in language-processing areas seem to emerge from limited reading exposure rather than being inherent from birth.

Reduced plasticity in the dyslexic brain

At this point, the logic seems simple: If the brain can change, why not use neuroplasticity — the foundation of learning — to heal dyslexia?

Unfortunately, there’s a complication.

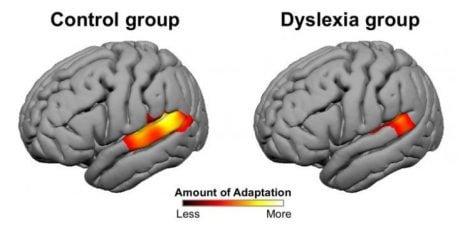

Researchers at MIT discovered that the brain’s ability to change — known as neural adaptation — is significantly reduced in individuals with dyslexia (Perrachione et al., 2016).

Their study used MRI scans to examine the brains of young adults with and without dyslexia during various tasks. First, participants listened to words spoken either by one person or by four different speakers. In individuals without dyslexia, language-related brain regions showed clear signs of adaptation when the same voice was repeated — but not when different voices were used. In contrast, participants with dyslexia showed much less adaptation, even when hearing repeated words from a single speaker.

Participants were shown repeated or different words, objects, and faces in a second experiment. Again, those with dyslexia exhibited reduced neural adaptation — not just in language areas but across brain regions responsible for visual and object recognition.

This led researchers to conclude that the reduced plasticity seen in dyslexia is not limited to reading or language. Instead, it reflects a broader difference in perceptual learning — the brain’s ability to adjust its response to repeated stimuli, whether verbal or nonverbal.

Finally, these findings were replicated in younger children. First- and second-grade students with dyslexia showed the same reduced neural adaptation as adults — suggesting that this diminished plasticity may be present from an early age.

What does it mean?

So, what do these findings mean for people with dyslexia?

Do they suggest that memorization and rote learning are ineffective strategies?

Do they imply that dyslexia cannot be overcome?

Were Clark and Gosnell right when they claimed, “Dyslexia is like alcoholism… it can never be cured” (1982, pp. 55–56)?

Or was James Hinshelwood ahead of his time — right to believe that dyslexia can be reversed?

While reduced plasticity may explain why children with dyslexia struggle to respond to traditional instruction, it doesn’t mean change is impossible. Far from it.

Once seen as a rigid machine, the brain is now known to be a powerhouse of adaptation. It has enabled humans to build spacecraft, create supercomputers, design complex transportation systems, and — perhaps most impressively — understand its own inner workings.

So, can this remarkable organ heal learning obstacles like dyslexia?

Research — and countless success stories — suggest that with the right approach, the answer is yes.

Next steps

Before continuing to Part 2 of this article, watch our playlist of customer reviews and see how Edublox’s cognitive training and tutoring programs help turn dyslexia around.

Edublox provides personalized cognitive training and live online reading instruction to students with dyslexia. We’ve helped students across the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond build the skills they need to succeed. Book a free consultation to talk with one of our specialists about your child’s unique learning needs — and how we can help.

Neuroplasticity Healing Dyslexia, Part 1: What Science Reveals was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational and reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

References for Neuroplasticity Healing Dyslexia, Part 1: What Science Reveals:

- Clark, M., & Gosnell, M. (1982, March 22). Dealing with dyslexia. Newsweek, 55-6.

- Dempsey-Jones, H., Wesselink, D. B., Friedman, J., & Makin, T. R. (2019). Organized toe maps in extreme foot users. Cell Reports, 28(11), 2748 Doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.027

- Doidge, N. (2007). The brain that changes itself. Penguin Publishing Group.

- Draganski, B., Gaser, C., Busch, V., Schuierer, G., Bogdahn, U., & May, A. (2004). Neuroplasticity: Changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature, 427, 311-2.

- Eriksson, P. S., Perfilieva, E., Björk-Eriksson, T., Alborn, A., Nordborg, C., Peterson, D. A., Gage, F. H. (1998). Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Natural Medicine, 4(11), 1313-7.

- Gaser, C., & Schlaug, G. (2003). Gray matter differences between musicians and nonmusicians. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 999, 514-7.

- Glezer, L. S., et al. (2016). Uncovering phonological and orthographic selectivity across the reading network using fMRI-RA. Neuroimage, 138, 248-256.

- Hinshelwood, J. (1895). Word-blindness and visual memory. Lancet, 146(3773), 1564-70.

- Hinshelwood, J. (1917). Congenital word-blindness. London: Lewis.

- Kadosh, R. C., & Walsh, V. (2006). Cognitive neuroscience: Rewired or crosswired brains? Current Biology, 16(22), R962-3.

- Keshav, M. (2018). The life transforming power of NLP. Chennai: Notion Press.

- Krafnick, A. J., Flowers, D. L., Luetje, M. M., Napoliello, E. M., & Eden, G. F. (2014). An investigation into the origin of anatomical differences in dyslexia. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(3).

- Maguire, E. A., Gadian, D. G., Johnsrude, I. S., Good, C. D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S. J., & Frith, C. D. (2000). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97(8), 4398-403.

- Maguire, E. A., Woollett, K., & Spiers, H. J. (2006). London taxi drivers and bus drivers: A structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis London taxi drivers and bus drivers. Hippocampus, 16(12), 1091-101.

- Mechelli, A., Price, C. J., Friston, K. J., & Ashburner, J. (2005). Voxel-based morphometry of the human brain: Methods and applications. Current Medical Imaging Reviews, 1, 105-13.

- Morgan, W. P. (1896). A case of congenital word blindness. British Medical Journal, 2(1871), 1378.

- Munte, T. F., Altenmuller, E., & Jancke, L. (2002). The musician’s brain as a model of neuroplasticity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(6), 473-8.

- Nudo, R. J. (2013). Recovery after brain injury: Mechanisms and principles. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7(887). Doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00887

- Opp, G. (1994). Historical roots of the field of learning disabilities: Historical roots of the field of learning disabilities: Some nineteenth-century German contributions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27, 10-9.

- Perrachione, T. K. , Del Tufo, S. N., Winter, R., Murtagh, J., Cyr, A., Chang, P., … Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2016). Dysfunction of rapid neural adaptation in dyslexia. Neuron, 92(6), 1383-97.

- Siugzdaite, R., Bathelt, J., Holmes, J., & Astle, D. E. (2020). Transdiagnostic brain mapping in developmental disorders. Current Biology, 30(7).

- Skeide, M. A., Kumar, M., Mishra, R. K., Tripathi, V. N., Guleria, A., Singh, J.P., … & Huettig, F. (2017). Learning to read alters cortico-subcortical cross-talk in the visual system of illiterates. Science Advances, 3(5).

- Sluming, V., Barrick, T., Howard, M., Cezayirli, E., Mayes, A., & Roberts, N. (2002). Voxel-based morphometry reveals increased gray matter density in Broca’s area in male symphony orchestra musicians. Neuroimage, 17(3), 1613–22.