Table of contents:

1. What is severe dyslexia?

2. The brain science behind severe dyslexia

3. A multi-deficit model

4. Why most reading programs don’t work for severe dyslexia

5. A promising approach for severe dyslexia

6. Emotional impact and long-term outlook

7. Conclusion

8. Talk to a specialist

9. Key takeaways

1. What is severe dyslexia?

Dyslexia exists on a spectrum and is generally described in three degrees: mild, moderate, and severe. Children with mild dyslexia may read more slowly than peers but can often compensate with support. Moderate dyslexia usually requires ongoing intervention, as difficulties in reading and spelling persist.

Severe dyslexia is in a class of its own. It involves not just difficulty with reading but a deep disruption in the brain systems responsible for connecting sounds to letters, recognizing words quickly, and processing language efficiently. Children and adults with severe dyslexia often face years of educational frustration, even with high intelligence and access to quality teaching.

Severe dyslexia is not officially a separate diagnosis from dyslexia, but it describes individuals whose reading struggles are intense, long-lasting, and resistant to conventional instruction. Common characteristics include:

- Severely impaired word recognition

- Extremely slow and effortful reading

- Major difficulties with spelling

- Limited progress, even after years of intervention

Their reading level often lags three or more years behind their peers, and they may struggle to learn high-frequency words despite repeated exposure.

2. The brain science behind severe dyslexia

Reading depends on a finely tuned network in the left hemisphere, involving regions that handle phonological decoding, word recognition, and language comprehension. In people with severe dyslexia, this network is disconnected, underactive, or inefficient—especially in the occipitotemporal and temporoparietal regions.

One critical hub in this network is the Visual Word Form Area (VWFA), located in the left occipitotemporal cortex. It becomes specialized through reading experience and enables readers to rapidly recognize written words as whole visual units—without sounding them out.

In severe dyslexia, studies show:

- Underactivation of the VWFA, even after years of conventional reading instruction.

- Delayed or absent specialization of this area for word forms (it remains responsive to general objects or faces rather than words).

- Weak functional connectivity between the VWFA and phonological/language areas (e.g., inferior frontal gyrus and superior temporal gyrus). Functional connectivity refers to how well different parts of the brain communicate and work together as a network during tasks like reading.

This means that children with severe dyslexia often cannot form quick, automatic visual word memories, making reading slow and effortful—even when they can decode phonetically. Instead of recognizing “elephant” at a glance, they may continue decoding it piece by piece, every time.

Other brain differences in severe dyslexia:

- Temporoparietal regions (phonological decoding): underactive, disrupting letter-sound mapping.

- Inferior frontal gyrus (articulatory rehearsal): often overactive as a compensatory mechanism.

- White matter pathways, especially the arcuate fasciculus, show reduced integrity, impairing communication between regions. White matter integrity describes the strength and efficiency of the brain’s communication highways that connect different regions involved in learning and language.

- Cerebellar differences: some evidence links cerebellar function to motor timing and automaticity in dyslexia.

These neurological differences explain why even high-quality teaching doesn’t always lead to reading improvement: the brain systems needed for reading are simply not working together effectively.

3. A multi-deficit model

To understand what makes severe dyslexia so persistent—and why standard teaching methods often don’t work—we must look at the multiple cognitive and brain-based issues contributing to it.

For several decades, the main explanation for dyslexia was a phonological deficit—a weakness in understanding and manipulating the sounds in spoken language. However, severe dyslexia often involves multiple cognitive weaknesses that go beyond phonology.

a. Rapid automatized naming (RAN)

RAN is the ability to quickly name familiar items like colors, numbers, letters, or objects. It sounds simple, but it’s one of the best predictors of reading fluency. RAN tasks require the brain to coordinate visual input, phonological retrieval, articulation, and timing—all at high speed.

Children with severe dyslexia often have very poor RAN scores, indicating a deeper problem with processing speed and automatic access to verbal labels. They may know a word but can’t retrieve it quickly, making reading laborious.

This finding led researchers to the “double-deficit hypothesis” (Wolf & Bowers, 1999), which proposes that the most severe cases of dyslexia involve both:

- A phonological deficit

- A rapid naming deficit

These children tend to show limited progress even with traditional phonics-based instruction.

b. Working memory and processing speed

Severe dyslexia is frequently linked to weak working memory, especially in the verbal domain. This makes it hard to retain and manipulate letter-sound sequences during decoding or spelling. Slow processing speed also affects how quickly students can connect written words to their meanings, making fluent reading almost impossible.

4. Why most reading programs don’t work for severe dyslexia

Many schools use evidence-based phonics programs like Orton-Gillingham, and while these can help students with mild to moderate dyslexia, they often do not go far enough for severe cases.

These programs are typically:

- Explicit: Explicit teaching practices involve showing students what to do and how to do it. Orton–Gillingham helps struggling readers by explicitly teaching the connections between letters and sounds.

- Multisensory: Multisensory learning is the theory that most individuals learn best when using more than one sense. A multisensory approach involves the visual, auditory, and kinesthetic/tactile learning pathways.

- Systematic: Systematic teaching means skills and concepts are taught in a planned, logically progressive sequence. For example, certain sounds — those easier to learn or used more often — are taught before other sounds.

- Incremental: With incremental teaching, each lesson builds carefully upon the previous. Each step serves as a building block to learning the English language.

- Cumulative: Two of the most important components of cumulative learning are mastery and constant and consistent review of previously taught skills and material.

- Based on phonograms: Phono means sound, and graph means written symbol. Phonograms are the letter symbols that comprise a sound. Phonograms may be one letter or letter teams.

- Individualized: Each student’s program gets tailored to suit their individual needs.

While effective for many, they do not directly address RAN, working memory, or processing speed. As a result, students may learn to decode but still read painfully slowly, with little comprehension and no enjoyment.

5. A promising approach for severe dyslexia

Though there is no single solution, intervention programs that address the full range of difficulties associated with severe dyslexia show promise (Jatau et al., 2024). These are programs that target multiple cognitive skills—RAN, working memory, processing speed, and phonological awareness. In addition, they provide reading instruction aligned with Orton Gillingham principles, mentioned above.

The videos below feature four students diagnosed with severe dyslexia. Their progress shows that significant gains can be made when multiple cognitive skills are developed alongside structured literacy instruction. Each began with persistent and significant reading and spelling challenges, yet all achieved measurable improvements in accuracy, fluency, and confidence after following this approach. Notably, Maddie’s reading improved by 54 percentile points, and Amy’s by 46.

6. Emotional impact and long-term outlook

Severe dyslexia takes a heavy emotional toll. Children may feel unintelligent, avoid reading, or develop anxiety and depression due to repeated failure. Misunderstood or unsupported, these children often internalize failure — reinforcing a negative feedback loop that further impairs learning.

Early diagnosis, supportive teachers, and family understanding are crucial. With the right intervention, individuals with severe dyslexia can become fluent readers and thrive academically and professionally.

7. Conclusion

Severe dyslexia is more than just “struggling to read.” It’s a complex brain-based condition involving multiple processing deficits—notably phonological awareness, rapid naming, processing speed, and working memory. Traditional reading programs help many but fall short for the most severely affected.

To truly support these learners, we must move beyond one-size-fits-all solutions and embrace multi-sensory and cognitively-informed interventions. With the right approach, students with severe dyslexia can unlock their potential and find success—not just in reading but in life.

8. Talk to a specialist

If you suspect your child may have dyslexia, do not wait. Getting the right help early can change the trajectory of their academic confidence and future.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, including those with severe dyslexia. Our programs go beyond reading instruction to target the root learning challenges behind reading struggles.

We support families across the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond.

Book a free consultation

Let’s talk about your child’s unique challenges — and how we can support their success.

9. Key takeaways

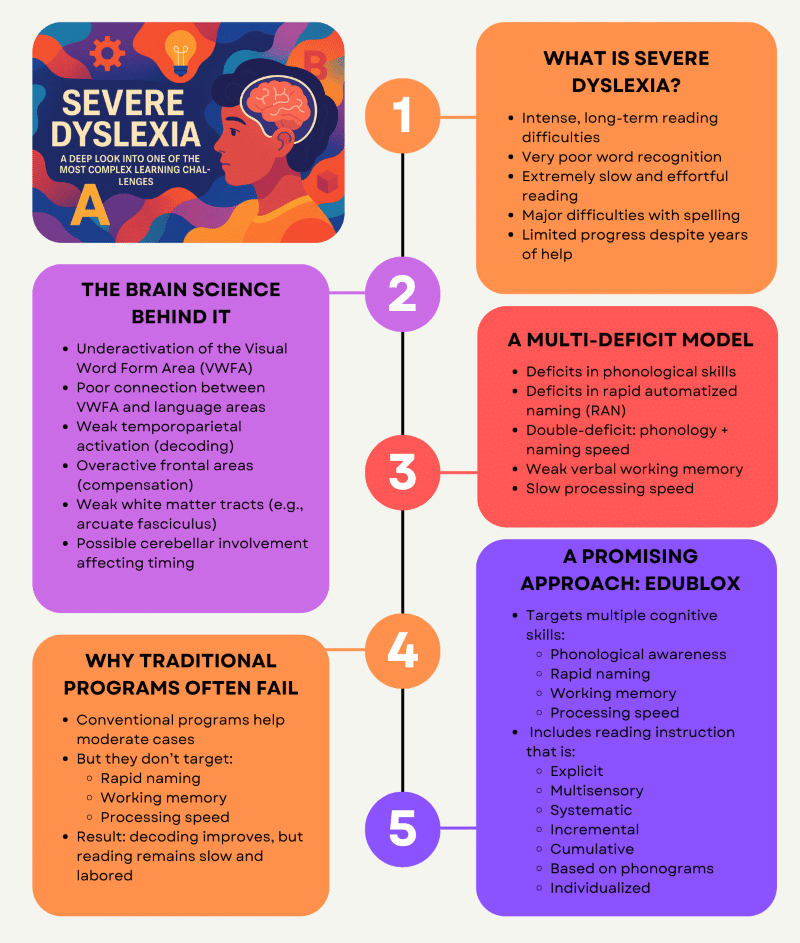

See the infographic below for a summary of key concepts.

References:

- Bowers, P. N., & Kirby, J. R. (2010). Effects of morphological instruction on vocabulary acquisition. Reading and Writing, 23(5), 515–537.

- Jatau, M. N., Bodang, J. R., & Jurmang, I. J. (2024). Effects of Audiblox programme on word recognition ability of pupils with reading difficulties in Pankshin Local Government Area, Nigeria. Journal of Human, Social and Political Science Research, 5(6). (Edublox is the evolved form of Audiblox)

- Shaywitz, S. (2020). Overcoming Dyslexia (2nd ed.). Knopf.

- Torgesen, J. K., Alexander, A. W., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Voeller, K. K., & Conway, T. (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34(1), 33–58.

- Wolf, M., & Bowers, P. G. (1999). The double-deficit hypothesis for the developmental dyslexias. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 415–438.

- Ziegler, J. C., Perry, C., Ma-Wyatt, A., Ladner, D., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2008). Developmental dyslexia in different languages: Language-specific or universal? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 101(3), 418–445.

Authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyslexia specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

Edublox is proud to be a member of the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), a leading organization dedicated to evidence-based research and advocacy for individuals with dyslexia and related learning difficulties.