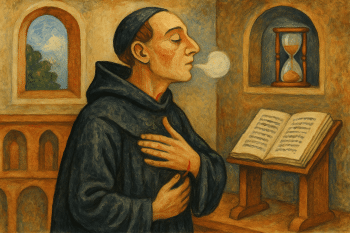

The rhythm of devotion

Long before ticking clocks and glowing screens, silence ruled the monastery. For medieval monks, life was divided not by hours on a dial but by prayer, work, and contemplation. Yet even in silence, time had to be kept. The solution? The body itself became the clock.

Breath as a metronome

Monks often counted their own breathing to pace prayers and rituals. A short psalm might take forty slow breaths; a vigil could stretch over hundreds. Each inhalation and exhalation was a unit of sacred time, reminding them of Genesis: “And the Lord God breathed into his nostrils the breath of life.” To breathe was to mark both mortality and eternity.

The heartbeat clock

In some traditions, monks used their pulse instead. Pressing fingers to the wrist or neck, they felt the steady beat and silently counted. A hundred heartbeats might equal the time needed to boil an egg; a thousand could mark the space between canonical prayers. In the stillness of the cloister, the human pulse became a living pendulum.

The problem of accuracy

Breath and heartbeat, however, are fickle. A racing pulse during fasting or a shiver in the cold could throw the rhythm off. Yet this imprecision was not a flaw — it was a feature. Monastic timekeeping was not about mechanical precision but about keeping the body and spirit aligned. Time was felt, not measured.

Echoes in modern science

Centuries later, psychologists would rediscover the link between the body and time perception. Studies show that people estimate intervals differently depending on arousal, temperature, or even emotion. A fearful moment feels longer; a joyful one shorter. The monks, in their silent experiments, already knew: the body bends time.

Silence as mathematics

We tend to think of mathematics as numbers written on parchment. But for monks, math lived in silence. Breaths added up, heartbeats multiplied, sequences of prayer repeated in perfect ratios. They built invisible equations in the cloister, balancing spirit and body, sound and silence.

Closing thought

Today, we consult atomic clocks that measure vibrations of cesium atoms with unimaginable precision. Yet in the stillness of an ancient chapel, a monk might smile: for him, time was never in the stars or in machines, but in the quiet rise of his chest and the steady thrum of his heart.

“Before clocks, the body was the calendar, and silence the mathematician.” — Stanley Armani

Timekeeping Before Clocks: How Monks Used Breath and Heartbeat was authored by Stanley Armani. Stanley writes about the brain, learning, and the hidden patterns that shape how we think. His work explores the strange, the hopeful, and the extraordinary sides of human potential.