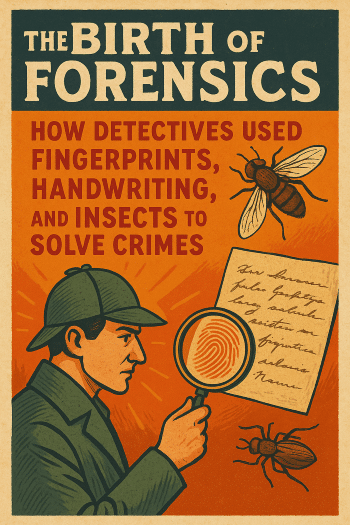

The crime scene before forensics

Imagine a murder in 1800. A body is discovered, a crowd gathers, and the local constable questions neighbors. Evidence — footprints, fingerprints, even blood — lies in plain view, but without science, it means almost nothing. Trials often relied on eyewitness accounts or confessions, sometimes forced. It was guesswork cloaked as justice. Then slowly, piece by piece, a new science was born: forensics.

The fingerprint revolution

One of the first breakthroughs was the fingerprint. The idea that fingerprints were unique dates back centuries — the ancient Chinese used them on contracts — but it wasn’t until the 19th century that detectives began to see them as evidence.

In 1892, an Argentine detective named Juan Vucetich solved the case of Francisca Rojas, accused of murdering her two children. A bloody fingerprint at the scene matched her own. It was the first time a fingerprint convicted a killer. From then on, the whorls and loops of human skin became a courtroom language, one more reliable than memory or hearsay.

Across the Atlantic, Scotland Yard created the Fingerprint Bureau in 1901. Suddenly, criminals could no longer hide behind false names or alibis. The skin itself betrayed them.

Handwriting as a window

Even before fingerprints, investigators turned to handwriting. The belief was simple: just as no two fingerprints are the same, no two people write in precisely the same way. The tilt of letters, the pressure of ink, the rhythm of curves — all became clues.

One famous early case was the Dreyfus Affair in France in the 1890s. Captain Alfred Dreyfus was accused of treason, mainly based on a handwritten memorandum. Experts testified about the shape of his strokes, igniting debates not just in court but across Europe. Although the trial was riddled with prejudice and error, it highlighted the growing power of forensic handwriting analysis. The pen, like the fingerprint, could become a witness.

The insect detectives

Perhaps the strangest forensic pioneers were insects. Long before modern entomology, investigators noticed that flies appeared on corpses in predictable patterns. In 13th-century China, a judge named Song Ci described how blowflies swarmed a farmer’s sickle after a murder, revealing it as the weapon. His book, The Washing Away of Wrongs, is sometimes called the first forensic manual.

Centuries later, in 19th-century France, Dr. Jean Pierre Mégnin studied the life cycles of maggots and beetles on corpses. He showed that insects could help estimate the time of death — a gruesome but crucial clue. If a body crawled with third-stage larvae, it had been dead for days, not hours. The buzzing of flies became testimony.

Blood and chemistry

Forensics also grew in the laboratory. In 1836, British chemist James Marsh developed a reliable test for arsenic poisoning. Before Marsh, suspected poisoners often went free because chemical evidence was too fragile to present in court. His “Marsh test” made invisible poisons visible — and hangings followed.

Later, scientists learned to type blood. By the early 20th century, knowing whether a suspect’s blood type matched a stain could strengthen a case. It was far from today’s DNA precision, but it was a leap forward: blood was no longer just a stain; it was a signature.

Photography and the new detective’s eye

Technology also reshaped investigations. In the 1860s, Alphonse Bertillon in Paris developed “criminal anthropology,” photographing criminals and measuring their bodies. His system of mugshots and body measurements, known as “Bertillonage,” briefly became the gold standard for identifying repeat offenders.

Though fingerprints eventually eclipsed Bertillon’s measurements, his mugshots remain with us. Every police booking photo today is a descendant of his idea: capture the body on film, freeze its identity, and make it evidence.

From guesswork to science

What made all these methods revolutionary wasn’t just their novelty. It was that they shifted the burden from human testimony to physical evidence. Witnesses could lie, memories could blur, but a fingerprint didn’t change. Politics didn’t sway a maggot’s age. Forensics promised an impartial voice — nature itself speaking in court.

Of course, imperfect beginnings

The early days of forensics were messy. Handwriting experts disagreed. Fingerprint systems were sometimes botched, leading to wrongful arrests. Insect analysis was imprecise. Yet even with flaws, these methods pushed justice forward. The courtrooms of the 19th century began to look less like theaters of drama and more like laboratories of truth.

Legacy and the modern crime lab

Today, forensics includes DNA sequencing, digital analysis, and 3D crime scene reconstruction. But every swab, every microscope slide, and every fingerprint dusted owes its place to those first leaps: the detective in Argentina who trusted a fingerprint, the chemist who tested for arsenic, the entomologist who read the story of a fly.

Closing thought

The birth of forensics was not one invention but many — fingerprints, handwriting, insects, chemistry, and photographs. Together they rewrote justice, transforming crimes from puzzles of rumor into problems of science. They remind us that truth is often hidden in the smallest of marks: a whorl on a fingertip, the curl of a letter, the buzz of a fly.

“Justice is never blind. It sees in fingerprints, in ink, in wings — in the evidence the world itself leaves behind.” — Stanley Armani

The Birth of Forensics: How Detectives Used Fingerprints, Handwriting, and Insects to Solve Crimes was authored by Stanley Armani. Stanley writes about the brain, learning, and the hidden patterns that shape how we think. His work explores the strange, the hopeful, and the extraordinary sides of human potential.