-

-

-

Where do IQ tests come from? What is the history of IQ tests?

-

What does IQ stand for? What do IQ scores mean?

-

What are IQ percentiles?

-

If an IQ test is supposed to measure a person’s intelligence, What is intelligence?

-

What does ‘multiple intelligences’ mean?

-

How reliable are IQ tests?

-

Can IQ be increased?

-

How can Edublox help?

-

Where can I have my child’s IQ tested?

-

-

Where do IQ tests come from? What is the history of IQ tests?

Intelligence testing began in earnest in France, when in 1904 psychologist Alfred Binet was commissioned by the French government to find a method to differentiate between children who were intellectually normal and those who were inferior. The purpose was to put the latter into special schools. There they would receive more individual attention and the disruption they caused in the education of intellectually normal children could be avoided.

This led to the development of the Binet Scale, also known as the Simon-Binet Scale in recognition of Theophile Simon’s assistance in its development. The test had children do tasks such as follow commands, copy patterns, name objects, and put things in order or arrange them properly. Binet gave the test to Paris schoolchildren and created a standard based on his data. For example, if 70 percent of 8-year-olds could pass a particular test, then success on the test represented the 8-year-old level of intelligence. Following Binet’s work, the phrase “intelligence quotient,” or “IQ,” entered the vocabulary. The IQ is the ratio of “mental age” to chronological age, with 100 being average. So, an 8-year-old who passes the 10-year-old’s test would have an IQ of 10/8 x 100, or 125.

It constituted a revolutionary approach to the assessment of individual mental ability. However, Binet himself cautioned against misuse of the scale or misunderstanding of its implications. According to Binet, the scale was designed with a single purpose in mind; it was to serve as a guide for identifying students who could benefit from extra help in school. He assumed that a lower IQ indicated the need for more teaching, not an inability to learn. It was not intended to be used as “a general device for ranking all pupils according to mental worth.” Binet also noted that “the scale, properly speaking, does not permit the measure of intelligence, because intellectual qualities are not superposable, and therefore cannot be measured as linear surfaces are measured.” Since, according to Binet, intelligence could not be described as a single score, the use of his Intelligence Quotient (IQ) as a definite statement on a child’s intellectual capability would be a serious mistake. In addition, Binet feared that IQ measurement would be used to condemn a child to a permanent “condition” of stupidity, this negatively affecting his or her education and livelihood:

H. H. Goddard & Lewis M. Terman

H. H. Goddard, director of research at Vineland Training School in New Jersey, decided that the Binet test would be a wonderful way to screen students for his school. He translated Binet’s work into English and advocated a more general application of the Simon-Binet Scale. He classified people as being normal, idiots, or imbeciles. Idiots could only develop to a mental age of three to seven years, while imbeciles could not progress to more than a three-year-old level. Goddard developed a new term, “morons,” to describe people who were somewhere between normal and idiots. Unlike Binet, Goddard considered intelligence a solitary, fixed and inborn entity that could be measured.

While Goddard extolled the value and uses of the single IQ score, Lewis M. Terman, who also believed that intelligence was hereditary and fixed, worked on revising the Simon-Binet Scale. His final product, published in 1916 as the Stanford Revision of the Binet-Simon Scale of Intelligence (also known as the Stanford-Binet), became the standard intelligence test in the United States for the next several decades. Convincing American educators of the need for universal intelligence testing, and the efficiency it could contribute to school programming, within a few years,

The founding fathers of the testing industry saw testing as one way of achieving the eugenicist aims. Goddard’s belief in the innateness and unalterability of intelligence levels, for example, was so firm that he argued for the reconstruction of society along the lines dictated by IQ scores:

According to Harvard professor Steven Jay Gould in his acclaimed book The Mismeasure of Man, these tests were also influential in legitimizing forced sterilization of allegedly “defective” individuals in some states.

By the 1920s, mass use of the Stanford-Binet Scale and other tests had created a multimillion-dollar testing industry. By 1974, according to the Mental Measurements Yearbook, 2,467 tests measuring some form of intellectual ability were in print, 76 of which were identified as strict intelligence tests. In one year in the 1980s, teachers gave over 500 million standardized tests to children and adults across the United States. In 1989 the American Academy for the Advancement of Science listed the IQ test among the twenty most significant scientific discoveries of the century along with nuclear fission, DNA, the transistor, and flight. Patricia Broadfoot’s dictum that “assessment, far more than religion, has become the opiate of the people,” has come of age.

.

What does IQ stand for? What do IQ scores mean?

Although the IQ test industry is already a century old, IQ scores are still often misunderstood. Comments like, “What do you mean my child isn’t gifted — he got 99 on those tests! That’s nearly a perfect score, isn’t it?” or “The criteria you handed out says ‘a score in the 97th percentile or above.’ Jane got an IQ score of 97! That meets the requirement, doesn’t it?” are not unusual and indicate a complete misunderstanding of IQ scores.

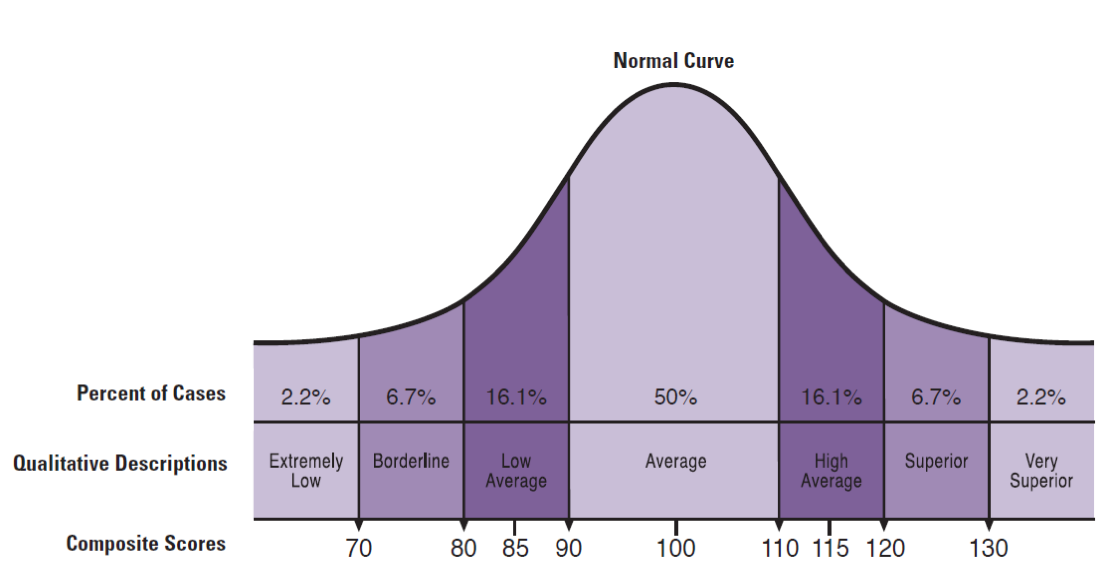

IQ stands for intelligence quotient. Supposedly, an IQ score tells one how “bright” a person is compared to other people. The average IQ is by definition 100; scores above 100 indicate a higher than average IQ and scores below 100 indicate a lower than average IQ. Theoretically, scores can range any amount below or above 100, but in practice, they do not meaningfully go much below 50 or above 150.

Half of the population have IQ’s of between 90 and 110, while 25% have higher IQ’s and 25% have lower IQ’s:

| IQ | Description | % of Population |

|---|---|---|

| 130+ | Very superior | 2.2% |

| 120–129 | Superior | 6.7% |

| 110–119 | High average | 16.1% |

| 90–109 | Average | 50% |

| 80–89 | Low average | 16.1% |

| 70–79 | Borderline | 6.7% |

| XX69 and belowXXXX | Extremely lowXX | 2.2%XXXXXXXXXXXX |

.

Below is a graphic representation of the above:

.

What are IQ percentiles?

IQ is often expressed in percentiles, which is not the same as percentage scores, and a common reason for misunderstanding IQ scores. Percentage refers to the number of items that a child answers correctly compared to the total number of items presented. If a child answers 25 questions correctly on a 50 question test, he would earn a percentage score of 50. If he answers 40 questions on the same test, his percentage score would be 80. Percentile, however, refers to the number of other test takers’ scores that an individual’s score equals or exceeds. If a child answered 25 questions and did better than 50% of the children taking the test, he would score at the 50th percentile. However, if he answered 40 questions on the 50 item test and everyone else answered more than he did, he would fall at a very low percentile — even though he answered 80% of the questions correctly.

On most standardized tests, an IQ of 100 is at the 50th percentile. Most of our IQ tests are standardized with a mean score of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. What that means is that the following IQ scores will be roughly equivalent to the following percentiles:

| IQ | Percentile |

| 65 | 01 |

| 70 | 02 |

| 75 | 05 |

| 80 | 09 |

| 85 | 16 |

| 90 | 25 |

| 95 | 37 |

| 100 | 50 |

| 105 | 63 |

| 110 | 75 |

| 115 | 84 |

| 120 | 91 |

| 125 | 95 |

| 130 | 98 |

| 135 | 99 |

If an IQ test is supposed to measure a person’s intelligence, What is intelligence?

Good question! Is it the ability to do well in school? Is it the ability to read well and spell correctly? Or are the following people intelligent?

Good question! Is it the ability to do well in school? Is it the ability to read well and spell correctly? Or are the following people intelligent?

- The physician who smokes three packets of cigarettes a day?

- The Nobel Prize winner whose marriage and personal life are in ruins?

- The corporate executive who has ingeniously worked his way to the top and also earned a heart attack for his efforts?

- The brilliant and successful music composer who handled his money so poorly that he was always running from his creditors (incidentally, his name was Mozart)?

.

The problem is that the term intelligence has never been defined adequately, and therefore nobody knows what an IQ test is supposed to measure. However, most psychologists agree that intelligence is a person’s ability to solve problems and that there are two main types of intelligence:

- Verbal intelligence is the ability to analyze information and solve problems using language-based reasoning. Language-based reasoning may involve reading or listening to words, conversing, writing, or even thinking. From classroom learning to social communication to texting and email, our modern world is built around listening to or reading words for meaning and expressing knowledge through spoken language.

. - Nonverbal intelligence is the ability to analyze information and solve problems using visual or hands-on reasoning. In other words, it is the ability to make sense of and act on the world without necessarily using words.

.

Most IQ tests consist of several verbal IQ subtests that measure verbal intelligence indicators, such as acquired knowledge, verbal reasoning, and comprehension of verbal information. Below is a question that would require verbal reasoning ability:

Butcher is to knife as hairdresser is to

a.) scissors

b.) hair

c.) curls

d.) blond.

Answer: a

Performance IQ (also called nonverbal IQ) subtests measure nonverbal intelligence indicators, such as spatial processing skills, attentiveness to detail, and visual-motor coordination skills. Below is a question that would require nonverbal reasoning ability:

Answer: d

What is expected in most people is that the full-scale IQ, verbal IQ, and performance IQ scores will cluster close enough together to indicate that the individual’s verbal and performance skills are evenly developed. When there is a large difference between verbal and performance scores, it may indicate a learning difficulty or impairment of some kind. For instance, a nonverbal learning difficulty (NVLD) is usually suspected when a child demonstrates a verbal IQ that is 20 or more points higher than their performance IQ. Low-performance IQ, relative to verbal IQ, is also associated with reported hyperactivity in children.

.

What does “multiple intelligences” mean?

Many scholars doubt that there is such a thing as general intelligence. Intelligence is an encompassing term. Many people feel that intelligence includes such attributes as creativity, persistent curiosity, and success. Consider, for example, that James Watson, the discoverer of DNA, has an IQ of about 115 — about the IQ of most college students. He claims that his great success was due to his persistent curiosity, something not measured by IQ tests. IQ tests, however, are poor indicators of many attributes of this nature. Generally, IQ tests seem to measure common skills and abilities, most of which are acquired in school. Thus, in opposition to the idea of a general intelligence, the concept of “multiple intelligences” came into being.

Undoubtedly, the man who stands out from the crowd for formally introducing the idea of multiple intelligences was L.L. Thurstone (1887-1955). Thurstone was a mathematician who had been hired to work in Thomas Edison’s laboratory. Thurstone soon became aware that Edison seemed completely unable to comprehend mathematics. This led Thurstone to conclude that, rather than a single quality called general intelligence, there must be many kinds of intelligence, perhaps each unrelated to the other. Thurstone believed that if a person was intelligent in one area, it didn’t necessarily mean that he would be intelligent in another. One of Thurstone’s goals was to isolate social from nonsocial intelligence, academic from nonacademic intelligence, and mechanical from abstract intelligence.

Based on his factor analysis of the human intellect, J. P. Guilford developed a model of intelligence. Guilford’s structure of the intellect is shown to the right. The figure is shown in three dimensions. Each side of the block represents a major intellectual function. Each function is divided into sub-functions. The total number of interactions possible is 120, since Guildford had isolated 120 different kinds of intelligence.

Probably the best-known theory of multiple intelligences was developed in 1983 by Dr. Howard Gardner, professor of education at Harvard University. Dr. Gardner proposes eight different intelligences to account for a broader range of human potential in children and adults. These intelligences are:

- Linguistic intelligence (“word smart”)

- Logical-mathematical intelligence (“number/reasoning smart”)

- Spatial intelligence (“picture smart”)

- Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence (“body smart”)

- Musical intelligence (“music smart”)

- Interpersonal intelligence (“people smart”)

- Intrapersonal intelligence (“self smart”)

- Naturalist intelligence (“nature smart”)

.

How reliable are IQ tests?

The unreliability of IQ tests has been proved by numerous researchers. The scores may vary by as much as 15 points from one test to another, while emotional tension, anxiety, and unfamiliarity with the testing process can greatly affect test performance. In addition, Gould described the biasing effect that tester attitudes, qualifications, and instructions can have on testing.

In one study, ninety-nine school psychologists independently scored an IQ test from identical records and came up with IQs ranging from 63 to 117 for the same person. In another study, Ysseldyke et al. examined the extent to which professionals were able to differentiate learning-disabled (LD) students from ordinary low achievers by examining patterns of scores on psychometric measures. Subjects were 65 school psychologists, 38 special-education teachers, and a “naive” group of 21 university students enrolled in programs unrelated to education or psychology. Provided with forms containing information on 41 test or subtest scores (including the WISC-R IQ test) of nine school-identified LD students and nine non-LD students, judges were instructed to indicate which students they believed were learning disabled and which were non-learning disabled. The school psychologists and special-education teachers were able to differentiate between LD students and low achievers with only 50 percent accuracy. The naive judges, who had never had more than an introductory course in education or psychology, evidenced a 75 percent hit rate!

In one study, ninety-nine school psychologists independently scored an IQ test from identical records and came up with IQs ranging from 63 to 117 for the same person. In another study, Ysseldyke et al. examined the extent to which professionals were able to differentiate learning-disabled (LD) students from ordinary low achievers by examining patterns of scores on psychometric measures. Subjects were 65 school psychologists, 38 special-education teachers, and a “naive” group of 21 university students enrolled in programs unrelated to education or psychology. Provided with forms containing information on 41 test or subtest scores (including the WISC-R IQ test) of nine school-identified LD students and nine non-LD students, judges were instructed to indicate which students they believed were learning disabled and which were non-learning disabled. The school psychologists and special-education teachers were able to differentiate between LD students and low achievers with only 50 percent accuracy. The naive judges, who had never had more than an introductory course in education or psychology, evidenced a 75 percent hit rate!

Measures of intelligence may be valuable, but much harm can be done by persons who try to classify individuals strictly on the basis of such measures alone. The IQ is, at best, a rough measure of academic intelligence. It certainly would be unscientific to say that an individual with an IQ of 110 is of high average intelligence, while an individual with an IQ of 109 is of only average intelligence. Such a strict classification of intellectual abilities would fail to take account of social elements such as home, school, and community. These elements are not adequately measured by present intelligence tests.

.

Can IQ be increased?

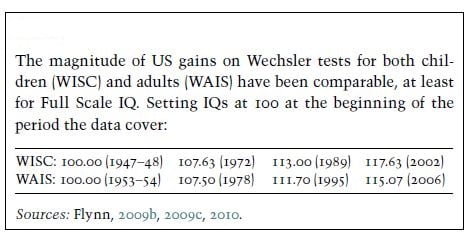

IQ scores have increased with passing generations. This is known as the Flynn effect, named for researcher James R. Flynn. Since the 1930s when standardized tests first became widespread, researchers have noted a sustained and significant increase in test scores among people all over the world. IQ test creators thus frequently have to revisit and re-code IQ tests to establish criteria for assigning a person an IQ, so that an IQ score of 100 is always average.

The box below shows how large American gains have been on the most frequently used tests, namely, the WISC (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children) and the WAIS (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale). These show full-scale IQ gains proceeding at 0.30 points per year over the last half of the twentieth century, a rate often found in other nations, for a total gain of over 15 points (Flynn, 2012).

The Flynn effect seems to be a consequence of several interrelated factors. Educational progress during the twentieth century seems to be a strong factor underlying the Flynn effect. Several studies have shown the impact of schooling on intelligence (Ceci & Williams, 1997). During the last century, in industrialized countries, schooling became compulsory. The percentage of children attending secondary and higher education programs strongly increased. In the same period, the percentage of illiterate people dropped sharply. Moreover, a growing number of children attended nursery school regularly, with a clear impact on their intellectual development (Fernandez-Ballesteros & Juan-Espinosa, 2001).

IQ is most certainly not a fixed quantity. This was also demonstrated by the Milwaukee project, an experiment at the Glenwood State School, as well as numerous other research studies.

The Milwaukee project

In the late 1960s, under the supervision of Rick Heber of the University of Wisconsin, a project was begun to study the effects of intellectual stimulation on children from deprived environments. In order to find a “deprived environment” from which to draw appropriate subjects for the study, Heber and his colleagues examined the statistics of different districts within the city of Milwaukee. One district, in particular, stood out. The residents of this district had the lowest median income and lowest level of education to be found in the city. This district also had the highest population density and rate of unemployment of any area of Milwaukee. There was one more statistic that really attracted Heber’s attention: Although this district contained only 3 percent of the city’s population, it accounted for 33 percent of the children in Milwaukee who had been labeled “mentally retarded”!

At the beginning of the project, Heber selected forty newborns from the depressed area of Milwaukee he had chosen. The mothers of the infants selected all had IQs below 80. As it turned out, all of the children in the study were non-Caucasian, and in many cases the fathers were absent. The forty newborns were randomly assigned, 20 to an experimental group and 20 to a control group.

Both the experimental group and the control group were tested an equal number of times throughout the project. An independent testing service was used to eliminate possible biases on the part of the project members. In terms of physical or medical variables, there were no observable differences between the two groups.

The experimental group entered a special program. Mothers of the experimental group children received education, vocational rehabilitation, and training in homemaking and child care. The children themselves received personalized enrichment in their home environments for the first three months of their lives, and then their training continued at a special center, five days a week, seven hours a day until they were ready to begin first grade. The program at the center focused on developing the language and cognitive skills of the experimental group children. The control group did not receive special education or home-based intervention and enrichment.

By the age of six, all the children in the experimental group were dramatically superior to the children in the control group. This was true on all test measures, especially those dealing with language skills or problem-solving. The experimental group had an IQ average of 120.7 as compared with the control group’s 87.2!

At the age of six, the children left the center to attend the local school. By the time both groups were ten years old and in fifth grade, the IQ scores of the children in the experimental group had decreased to an average of 105 while the control group’s average score held steady at about 85. One possible reason for the decline is that schooling was geared toward the slower students. The brighter children were not given materials suitable for their abilities, and they began to fall back. Also, while the experimental children were in the special project center for the first six years they ate well, receiving three hot, balanced meals a day. Once they left the center and began to attend the local school, many reported going to classes hungry, without breakfast or a hot lunch.

The Glenwood State School

Research on the role of the environment in children’s intellectual development has shown that a stimulating environment can dramatically increase IQ, whereas a deprived environment can lead to a decrease in IQ. A particularly interesting project on early intellectual stimulation involved 25 children in an orphanage. These children were seriously environmentally deprived because the orphanage was crowded and understaffed. Thirteen babies of the average age of 19 months were transferred to the Glenwood State School for intellectually disabled adult women, and each baby was put in the personal care of a woman. Skeels, who conducted the experiment, deliberately chose the most deficient orphans to be placed in the Glenwood School. Their average IQ was 64, while the average IQ of the 12 who stayed behind in the orphanage was 87.

In the Glenwood State School, the children were placed in open, active wards with the older and relatively brighter women. Their substitute mothers overwhelmed them with love and cuddling. Toys were available, they were taken on outings and they were talked to a lot. The women were taught how to stimulate the babies intellectually and how to elicit language from them.

After 18 months, the dramatic findings were that the children who had been placed with substitute mothers, and had therefore received additional stimulation, on average showed an increase of 29 IQ points! A follow-up study was conducted two and a half years later. Eleven of the 13 children originally transferred to the Glenwood home had been adopted and their average IQ was now 101. The two children who had not been adopted were reinstitutionalized and lost their initial gain. The control group, the 12 children who had not been transferred to Glenwood, had remained in institution wards and now had an average IQ of 66 (an average decrease of 21 points).

More telling than the increase or decrease in IQ, however, is the difference in the quality of life these two groups enjoyed. When these children reached young adulthood, another follow-up study brought the following to light: “The experimental group had become productive, functioning adults, while the control group, for the most part, had been institutionalized as mentally retarded.”

In another home-based early enrichment program, conducted in Nassau County, New York, an instructor made only two half-hour visits a week for only seven months over a period of two years. He spent time showing parents participating in the program how best to teach their children at home. The children in the program had initial IQs in the low 90s, but by the time they went to school they averaged IQs of 107 or 108. In addition, they have consistently demonstrated superior ability on school achievement tests.

.

How can Edublox help?

In 1987 Dr. Wynand de Wet did his practical research for a Master’s degree in Educational Psychology at a school for the deaf. The subject of his research project concerned the optimization of intelligence. The group who did Edublox were tutored simultaneously for 27.5 hours between April and August of that year, and showed an increase of 11.625 in non-verbal IQ, from an average of 101.125 to an average of 112.75.

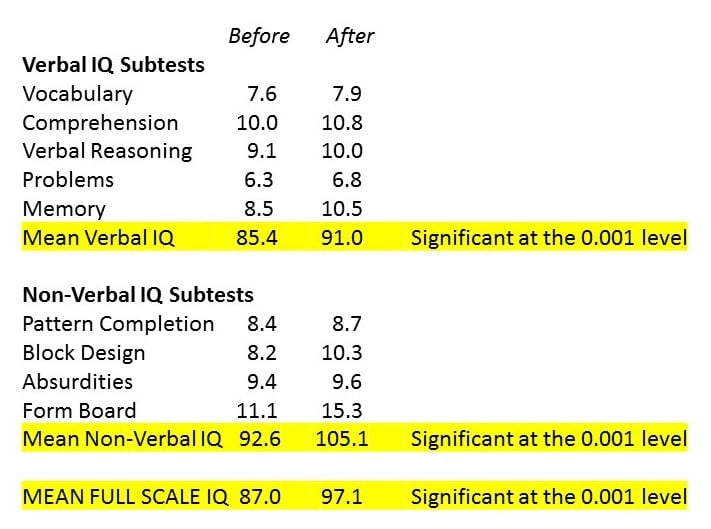

Our own trials confirmed that Edublox increases IQ scores. In one experiment the IQs of ten youngsters with severe learning difficulties were tested before starting on the program, and again after receiving 40 hours of one-on-one instruction. Their ages were between 7 and 18. The mean verbal IQ score increased from 85.4 to 91.0, the mean non-verbal IQ score from 92.6 to 105.1, and the mean full scale IQ from 87.0 to 97.1.

The increases in verbal, non-verbal and full scale IQ were highly significant according to the two-tailed t-test.

Where can I have my child’s IQ tested?

An IQ test can be administered by a licensed psychologist, but there are also online IQ tests for kids available at a cost of only $19.99.

.

References:

- Armstrong, T., In Their Own Way: Discovering and Encouraging Your Child’s Personal Learning Style (Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher, Inc., 1987).

- Bjorklund, D. F., Children’s Thinking: Development Function and Individual Differences (Pacific Grove, CA: Brookes/Cole, 1989).

- Broadfoot, P., cited in Engelbrecht et al. (eds.), Perspectives on Learning Difficulties, 109.

- Buros, O. K. (ed.), Mental Measurements Yearbook (Highland Park, NJ: Gryphon Press).

- Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (1997). Schooling, intelligence, and income. American Psychologist, 52, 1051–1058.

- Dworetzky, J. P., Introduction to Child Development (St. Paul: West Publishing Company, 1981).

- Engelbrecht, S. Kriegler & M. Booysen (eds.), Perspectives on Learning Difficulties (Pretoria: J. L. van Schaik, 1996).

- Epps, S., Ysseldyke, J. E., & McGue, M., “’I know one when I see one’ — Differentiating LD and non-LD students,” Learning Disability Quarterly, 1984, vol. 7, 89-101.

- Fernandez-Ballesteros, R., & Juan-Espinosa, M. (2001). Sociohistorical changes and intelligence gains. In R. J. Sternberg, & E. L. Grigorenko (Eds.). Environmental effects on cognitive abilities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Flynn, J. R. (2012). Are we getting smarter? Rising IQ in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Goddard, H. H., Human Efficiency and Levels of Intelligence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1920).

- Gould, S. J., The Mismeasure of Man (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981).

- Linden, K. W., & Linden, J. D., Modern Mental Measurement: A Historical Perspective (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1968).

- Lippman, cited in N. J Block & G. Dworkin (eds.), The IQ Controversy: Critical Readings (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976).

- National Education Association Handbook, 1984-85 (Washington, DC: National Education Association of the United States, 1984, 240), cited in Armstrong, In Their Own Way, 27.

- New York Times, August 1979, cited in S. B. Sarason, Psychology Misdirected (New York: The Free Press, 1981).

- Osgood, “Intelligence testing and the field of learning disabilities: A historical and critical perspective,” Learning Disability Quarterly, 1984, vol. 7.

- Sattler, J., Assessment of Children’s Intelligences and Special Abilities (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1982), 60.

- Smith, C. R., Learning Disabilities: The Interaction of Learner, Task, and Setting (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1991), 63.

- Swiegers, D. J., & Louw, D. A., “Intelligensie,” in D. A. Louw (ed.), Inleiding tot die Psigologie(2nd ed.), (Johannesburg: McGraw Hill, 1982).

- Tyler, cited in A. Anastasi, (ed.), Testing Problems in Perspective (Washington DC: American Council on Education, 1966).

- Weiss, T., “The problem with IQ,” parentsinc.org

- Ysseldyke, J. E., & Algozzine, B., “LD or not LD: That’s not the question!” Journal of Learning Disabilities, 1983, vol. 16(1), 26-27.