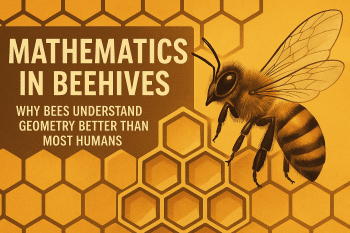

The humble mathematicians in your garden

Step into a beehive, and you’ll find a construction site humming with perfect order. No architects, no rulers, no CAD software—yet every honeycomb cell is a flawless hexagon. It’s geometry in its purest form, designed not by humans with compasses but by insects with instincts.

Why hexagons?

Of all shapes, why did bees choose the hexagon? They didn’t. Nature did. Mathematically, the hexagon is the most efficient way to tile a flat plane with equal-sized units. It covers space without gaps, uses the least material for the most storage, and provides maximum strength.

In 36 BC, the Roman scholar Marcus Varro described it as the “honeybee’s geometry theorem.” Centuries later, mathematicians proved him right. In fact, it wasn’t until the 1990s that Thomas Hales delivered a rigorous mathematical proof confirming what bees had known all along: the hexagon is nature’s most economical design.

The physics of wax and work

Bees aren’t just “good at geometry.” They’re energy accountants. Building a comb is expensive—it takes eight ounces of honey to produce a single ounce of wax. By instinctively choosing hexagons over circles or squares, bees save enormous amounts of energy and wax while storing the maximum honey.

It’s the ultimate return-on-investment calculation, coded into their tiny bodies. Even more striking, bees build cells tilted at a perfect angle—about 13 degrees upward—so honey doesn’t drip out. That’s not design school. That’s instinct meeting physics in a flawless partnership.

The self-building secret

Do bees sit around sketching blueprints? Hardly. Recent research suggests the comb’s shape is partly the result of physics. Bees initially make wax cylinders while the material is still warm and pliable. These cylinders press against one another, and surface tension combined with heat flow helps the walls settle into hexagons, just like soap bubbles clustering together.

In other words, bees are both builders and physicists, harnessing geometry and chemistry without knowing the words for either. The hive is a place where biology and physics quietly cooperate.

More than honey storage

The honeycomb isn’t only a pantry for honey. It’s also a nursery for the young, a stage for the famous waggle dance, and a communication hub where vibrations transmit messages. Its strength-to-weight ratio rivals some of the best human-made structures. Engineers studying lightweight construction often borrow from the hexagon, using honeycomb-inspired designs in airplanes, cars, and even space shuttles.

And while we marvel at skyscrapers and bridges, bees go on building perfect modular cities, generation after generation, without blueprints or committees.

Lessons from the hive

Bees remind us that mathematics is not an abstract human invention but a language written into the fabric of nature. Geometry, efficiency, symmetry—these are not only in textbooks but alive in the living world. Where we labor with protractors and formulas, bees live mathematics instinctively.

Their hives are monuments to geometry, efficiency, and the mysterious intelligence of instinct. Each perfect cell whispers a truth we often forget: the universe is built on patterns, and those patterns can emerge even in the tiniest of creatures.

Closing thought

We may have calculus, but the bees have perfect hexagons. In their dark, humming cities, they’ve solved problems of efficiency and design that humans still admire. And they do it without thinking. That, perhaps, is the most elegant equation of all.

✨ “Mathematics is not just for blackboards. Sometimes, it hums in a hive and drips with honey.” — Stanley Armani

Mathematics in Beehives: Why Bees Understand Geometry Better Than Most Humans was authored by Stanley Armani. Stanley writes about the brain, learning, and the hidden patterns that shape how we think. His work explores the strange, the hopeful, and the extraordinary sides of human potential.