Good day Sue

My son’s phonological awareness is average, yet he reads painfully slowly. I want information about your approach and how it supports children with a more orthographic type of dyslexia.

Phillipa

.

.

Dear Phillipa

Thank you for your question. Before answering directly, let me explain what orthographic dyslexia is, for the benefit of other readers.

Orthographic dyslexia is a subtype of dyslexia in which children struggle to recognize words by sight. You may also hear it referred to as surface dyslexia or dyseidetic dyslexia.

Recognizing words by sight matters for two reasons:

- Some words have irregular spellings (one, said, whose, people) and cannot easily be sounded out.

- Fluent reading requires recognizing many common words instantly, without having to sound them out each time.

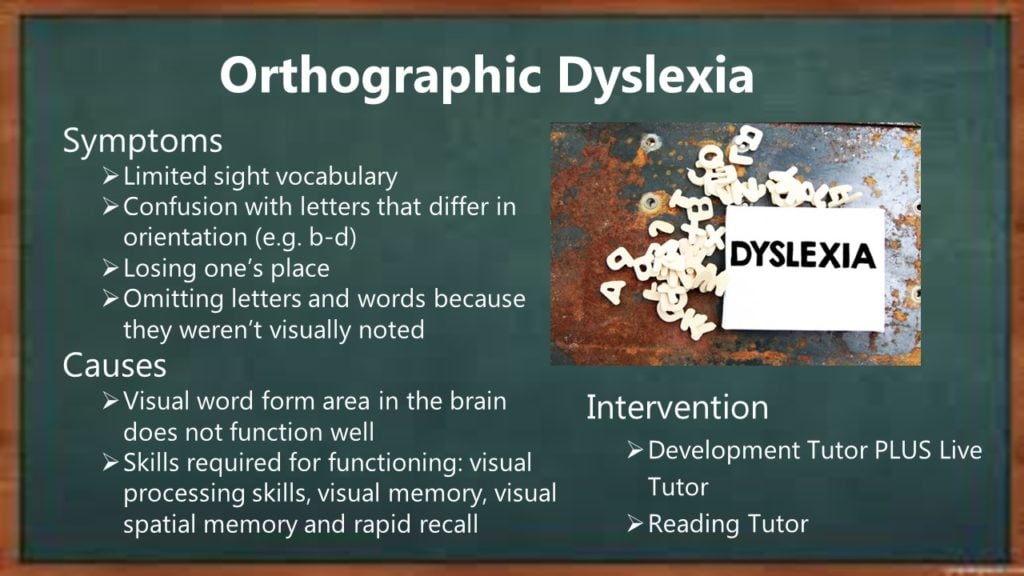

Symptoms of orthographic dyslexia

The most common symptom is a limited sight vocabulary. Words are not recognized automatically; they must be sounded out as if they were being read for the first time. Children with orthographic dyslexia also struggle to learn irregular words that cannot be decoded.

Other reading and spelling patterns associated with orthographic dyslexia include:

- Confusion with letters that differ in orientation (b–d, p–q) or reversible words (was/saw)

- Losing one’s place because previously read words are not instantly recognized

- Omitting letters or words that weren’t visually noted

- Difficulty recalling the shape of letters when writing

- Spelling that is phonetic but not bizarre (laf → laugh; bisnis → business)

- Spelling of difficult phonetic words, but not simple irregular ones

Most problems can only be solved if one understands their cause. For example, scurvy once claimed the lives of thousands of seamen during long voyages. The disease was quickly cured once its cause was identified — a deficiency of Vitamin C.

In the same way, a logical starting point is to ask, “What causes dyslexia?” In your son’s case, the more specific question is, “What causes orthographic dyslexia?”

Causes of orthographic dyslexia

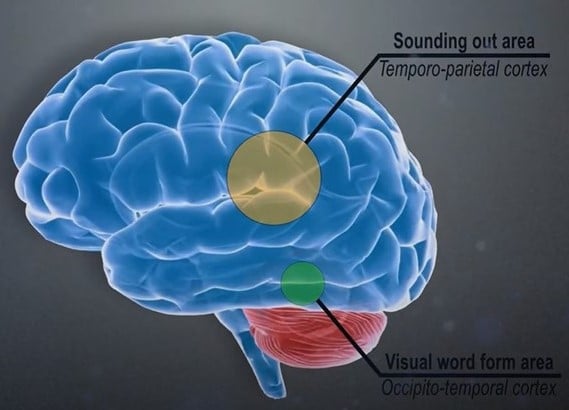

Two separate brain regions are involved in reading: one for sounding out words and another for recognizing words as visual patterns — the essence of sight reading.

Glezer et al. (2016) concluded that skilled readers recognize words at lightning speed because they are stored in a kind of visual dictionary. This part of the brain, the visual word form area (VWFA), operates independently from the region that processes word sounds. In people with orthographic dyslexia, the VWFA does not work as efficiently.

Glezer and colleagues tested word recognition in 27 volunteers using fMRI brain scans. They found that visually distinct words, even if they sounded the same — such as “hare” and “hair” — activated different neurons, as if accessing different dictionary entries. If sound influenced this brain area, we would expect hare and hair to look similar in neural activity, but they did not — hair and hare appeared just as different as hair and soup.

The researchers also identified a distinct sound-sensitive region where hair and hare did look alike. Their work showed that the brain specializes: one area is responsible for the visual aspect of reading, while another is responsible for the sound aspect. In orthographic dyslexia, the visual region — the VWFA — is most likely the weak link.

In the most extensive study of its kind, Brem et al. (2020) confirmed that the VWFA plays a central role in fluent reading. Pedago et al. (2011) further demonstrated its role in discriminating letter orientation, aligning with the well-known difficulty children with orthographic dyslexia have in distinguishing b from d.

Activating the VWFA

Although some causes of dyslexia are genetic (Kere, 2014), and environmental factors also play a role (Stein, 2018), cognition is what links brain and behavior. This makes it the most practical level for designing interventions. In other words, we need to understand the cognitive difficulties behind reading failure, regardless of whether their origin is biological or environmental (Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014).

For a child with orthographic dyslexia, intervention should therefore focus on the cognitive skills required to recognize words by sight.

- Phonics relies on phonological processing and auditory memory.

- Sight reading relies on visual skills, such as spatial relations, form discrimination, visual memory, and visual-spatial memory.

Students with orthographic dyslexia may also struggle with rapid recall — the speed at which names of familiar symbols (letters, numbers, colors, or pictured objects) can be retrieved from long-term memory (De Jong & van der Leij, 2003). This process, known as rapid automatized naming (RAN), is often weaker in individuals with dyslexia than in typical readers (Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014).

Intervention for orthographic dyslexia

The good news is that weaknesses in cognitive skills can be tackled directly — these mental skills can be strengthened through systematic training and practice.

At Edublox, our Development Tutor program focuses on developing the underlying cognitive skills most often associated with orthographic dyslexia, including visual processing, visual memory, visual-spatial memory, and rapid recall.

But cognitive strengthening alone isn’t enough. Children also need targeted reading and spelling practice. That’s where Edublox’s live tutoring comes in. While based on the proven Orton–Gillingham approach, our program also works to develop the brain’s visual word form area (VWFA) — helping students not just sound out words but recognize them automatically.

👉 Watch this playlist to see how Edublox training and tutoring help turn dyslexia around.

Key takeaways

Warm regards

Sue

More about Sue

Sue is an educational specialist in learning difficulties with a B.A. Honors in Psychology and a B.D. degree. Early in her career, Sue was instrumental in training over 3,000 teachers and tutors, providing them with the foundational and practical understanding to facilitate cognitive development among children who struggle to read and write. With over 30 years of research to her name, she conceptualized the Edublox teaching and learning methods that have helped thousands of children worldwide. In 2007, she opened the first Edublox reading and learning clinic; today, there are 30 clinics internationally. Sue treasures the “hero” stories of students whose self-esteem soars as their marks improve.