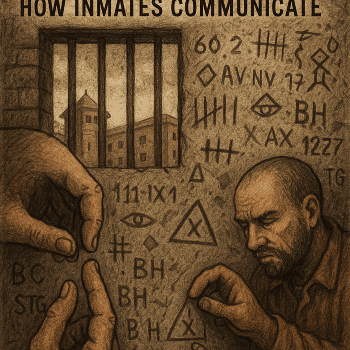

Walls talk

Behind prison walls, silence is not always what it seems. Inmates, cut off from the outside world and watched by guards, have always found ways to bend language, create secret codes, and speak when speech itself was forbidden. The history of prison communication is a story of resilience, invention, and the human refusal to be voiceless.

Scratching on stone

Long before mass incarceration, prisoners left marks on the walls of dungeons and cells. In the Tower of London, etchings from the 1500s remain — names, prayers, coded emblems. Some carved symbols of faith, others encoded dates or initials so future prisoners might know who had come before them. The scratches were more than graffiti; they were messages across time, linking the condemned in a chain of silent solidarity.

Hand signs and whispers

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, prisoners developed hand signs resembling early versions of gang language. Inmates in overcrowded penitentiaries would touch their ears or tilt their heads in ways that looked like idle fidgets but carried specific meanings: danger, loyalty, or a call for help. Whispers were riskier, but prisoners learned to manipulate coughs, sneezes, and throat clears into disguised signals, turning the body itself into a codebook.

Tap codes in solitary

Perhaps the most famous prison code is the tap code, a grid-based system where letters are transmitted through knocking on walls or pipes. The system was famously used by American POWs in Vietnam, who tapped messages from cell to cell. But the method has much older roots. Political prisoners in 19th-century Europe used similar grids, tapping out alphabets that allowed them to “talk” even in total isolation.

The rules were simple but powerful:

- A 5×5 grid of letters, with “C” and “K” often combined.

- One set of knocks to signal the row, another to signal the column.

- Example: “H” (row 2, column 3) would be tap-tap, pause, tap-tap-tap.

For someone starved of human contact, a message tapped through stone could mean survival.

Coded writing and invisible ink

Smuggling letters out of prison demanded creativity. Prisoners wrote in microscopic script along the edges of newspapers. Some dipped matchsticks in milk or lemon juice to create invisible ink that could be revealed with heat. Others hid entire pages inside hollowed-out books or sewed them into the lining of clothes. Guards might intercept some messages, but ingenuity always found new channels.

Tattoos as text

The skin itself became a canvas. Russian prisons perfected the art of coded tattoos — stars, crosses, barbed wire, even cats all carried meaning. A star on the shoulders could mean “I bow to no authority.” Barbed wire across the forehead signaled a life sentence with no chance of parole. These tattoos weren’t just art; they were maps of rank, reputation, and resistance inked directly onto the body.

Food, laundry, and chess

Objects became messengers. Inmates passed notes wrapped in bread, rolled into cigarettes, or hidden under food trays. Laundry marked with particular folds or stains could signal allegiance or warnings. Even chess games were coded: a pawn moved in a certain way might mean “I need medicine.” A rook shifted unusually could mean “I need to see you tonight.” To an outsider, it was just a game. To insiders, it was a living telegram.

Gangs and symbolic alphabets

Modern prison gangs expanded this tradition with entire alphabets, ciphers, and glyphs. Some drew on ancient runes or Masonic symbols; others invented elaborate substitution codes. Gangs in the U.S. developed graffiti-like markings on cell walls and correspondence. A seemingly random scrawl could stand for a pledge of loyalty, a threat, or a warning about guards. Each group guarded its lexicon fiercely, making the ability to read and write it both a weapon and a shield.

The psychology of secrecy

Why do inmates pour so much energy into secret codes? Psychologists argue that it is about agency. In prison, almost everything is controlled: meals, movement, light, and time. To carve out a private channel of communication is to reclaim autonomy, however small. Codes also build trust and community. To share a secret language is to declare: we are us, and they are them. The code separates insiders from outsiders, prisoners from wardens, and sometimes even one gang from another.

Modern adaptations

Today, prison authorities scan letters, monitor calls, and even use AI to detect patterns of communication. But codes persist. Some inmates hide messages in Bible verses by referencing chapter and line. Others embed meaning in rap lyrics or poems written to their girlfriends. Social media smuggled out on contraband phones carries hashtags that double as signals. Even emojis have been retooled into prison code — a spider might mean a specific gang, a clock might signal a planned attack.

From prisons to culture

Interestingly, many of these codes leak into the outside world. Tap codes inspired resistance movements. Tattoo symbolism influenced fashion. Even hip-hop, born partly from prison culture, adopted coded slang that later spilled into mainstream language. What starts as survival in confinement often grows into cultural expression beyond the walls.

Closing thought

Prisons were designed to silence. Yet behind the walls, language refuses to die. In scratches on stone, in knocks on steel, in the ink beneath the skin, inmates have always spoken. Codes are not only about crime or conspiracy — they are about endurance. They remind us that even in cages, the human spirit invents ways to connect, to belong, and to resist.

“To control speech is to control people. To create codes is to remain free.” — Stanley Armani

The Secret Codes of Prisons: How Inmates Communicate was authored by Stanley Armani. Stanley writes about the brain, learning, and the hidden patterns that shape how we think. His work explores the strange, the hopeful, and the extraordinary sides of human potential.