Deer momee and dadee

I bo not wont to do to shool eny more.The children ar lafing at me.I canot reed.Pleese help me

Your sun David

David has what his father has

David is not a slow learner. In fact, several professionals who’ve assessed him agree—he’s bright. But he does have a serious challenge, one he shares with millions of children and adults around the world… and with his father.

David has dyslexia.

The term “dyslexia” comes from Greek and means “difficulty with words.” Today, it’s most commonly defined as a learning difficulty that affects reading and writing—especially spelling and putting thoughts down on paper.

Dyslexia falls under the umbrella of learning disabilities, and most experts agree that its root causes are either neurological or genetic. Some researchers point to subtle brain differences that may result from complications before, during, or shortly after birth. Others argue that these neurological differences are largely inherited, passed down from one generation to the next. Supporting this idea, numerous studies have found that dyslexia often runs in families.

Dyslexia runs in families, research confirms

Over the past several decades, researchers have consistently found that dyslexia tends to run in families. This isn’t just a coincidence or anecdote—scientific studies confirm a strong hereditary component to reading difficulties.

A landmark study by DeFries et al. (1978) investigated this familial link by recruiting 133 children identified by their teachers as having significant reading problems. These children were tested in the laboratory to confirm their difficulties. A control group of 125 children with normal reading ability was also evaluated. Crucially, both the parents and siblings of children in both groups were assessed.

The findings were unambiguous: the relatives of children with dyslexia were significantly more likely to also experience reading difficulties than the relatives of children without dyslexia. This provided compelling evidence that reading impairments often run in families and may have a genetic component (DeFries et al., 1978).

Twin studies have further strengthened the case for genetics. Because identical (monozygotic) twins share nearly 100% of their genes and fraternal (dizygotic) twins share only about 50%, comparing concordance rates between these groups can reveal how strongly a trait is influenced by heredity. A major study by DeFries and Alarcón (1996) found a concordance rate of 68% for dyslexia among identical twins, compared with only 38% among fraternal twins—evidence of a substantial genetic contribution.

Additional data comes from longitudinal and family-risk studies. A meta-analysis by Snowling and Melby-Lervåg (2016) reviewed 15 studies examining children with a family history of dyslexia. They found that, on average, 45% of these children eventually developed dyslexia themselves. The estimates varied by region—from 29% in a Dutch study to 66% in an English study—but the overarching trend was consistent: having a parent or sibling with dyslexia greatly increases a child’s risk.

Beyond statistical associations, molecular genetic studies have begun identifying specific genes and chromosomal regions linked to dyslexia. The Dyslexia Research Trust, for instance, studied nearly 400 families with at least one child with dyslexia. Their analysis revealed strong associations on the short arm of chromosome 6 (6p21) and on chromosome 18 (18p11), with one gene in particular—KIAA0319—showing robust links to poor performance in reading, spelling, and phonological processing tasks (Cope et al., 2005).

Other genes frequently implicated in dyslexia include DCDC2, DYX1C1, and ROBO1, all of which are thought to play roles in brain development, particularly in neural migration and connectivity in regions important for language (Paracchini et al., 2007; Scerri & Schulte-Körne, 2010).

Collectively, this growing body of evidence shows that dyslexia is not just an educational issue—it is, in large part, a neurodevelopmental condition with a strong genetic basis.

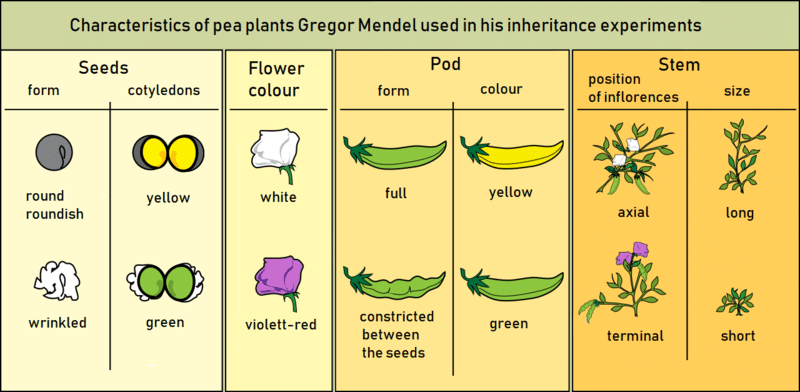

Dyslexia is not a Mendelian disorder

When Gregor Mendel presented his famous experiments with pea plants in 1865, he laid the foundation for modern genetics. His work demonstrated that certain traits—such as flower color or seed shape—are inherited in predictable patterns determined by single genes. This type of inheritance, now called Mendelian inheritance, is straightforward: if you inherit the gene, you get the trait.

Some medical conditions do follow this classic pattern. Huntington’s disease, for example, is caused by a mutation in a single gene and is passed from generation to generation with high predictability. If a person inherits the faulty gene, they almost certainly develop the condition.

However, many common disorders—such as heart disease, asthma, diabetes, and dyslexia—are far more complex. These conditions tend to run in families, but they do not follow the clean, predictable inheritance patterns of Mendelian disorders. Instead, they are influenced by many genetic variants, each of which contributes only a small increase in risk. It is the combination of these variants, along with environmental factors, that determines whether the condition actually develops.

This is precisely the case with dyslexia. As Bishop (2015) explains, dyslexia is not a Mendelian disorder. There is no single gene that causes it. Instead, it is a polygenic and multifactorial condition—meaning that many genes are involved, each playing a minor role in its development. In some cases, rare genetic variants with significant effects may be involved; however, these tend to affect only a small number of individuals. Most cases of dyslexia appear to result from the subtle, cumulative effects of dozens—perhaps hundreds—of common genetic differences, combined with specific environmental influences such as quality of instruction, early language exposure, or socioeconomic context.

Understanding dyslexia as a complex trait rather than a single-gene disorder helps explain its variability and heterogeneity. It also underscores the importance of both nature and nurture in shaping reading development.

Statistics must be interpreted with caution

While the evidence supporting a genetic component to dyslexia is compelling, it is crucial to remember that statistical correlations do not automatically imply causation. As Bishop (2015) points out, one of the major criticisms of genetic studies in dyslexia is the potential for misinterpreting such associations.

The observation that dyslexia “runs in families” may indeed reflect shared genetics—but it could also reflect shared environmental factors. Families often live in the same household, speak the same language, value the same behaviors, and access similar educational resources. These overlapping environmental influences can produce patterns that closely resemble genetic inheritance, making it challenging to distinguish one from the other.

To illustrate, imagine a family in which all children struggle with reading. One might be tempted to assume a hereditary cause. But if those children are growing up in a print-poor environment—one with few books, limited adult reading aloud, and inconsistent school attendance—then their difficulties could just as easily stem from the environment as from genes.

This distinction is not merely academic. In epidemiology and behavioral genetics, it’s well known that high concordance (agreement between individuals on a trait) does not confirm a genetic cause unless environmental factors have been properly controlled. Without such controls, any observed pattern might reflect shared experience.

For example, studies of adoptees—children raised apart from their biological parents—can help tease apart the effects of genes versus environment. When adopted children resemble their biological relatives more than their adoptive ones, genetic influence is implicated. However, when resemblance is greater within adoptive families, environmental influences take center stage.

In short, while familial clustering of dyslexia strongly suggests a heritable component, it must always be interpreted in the context of both shared genes and shared environments. Failing to do so risks drawing simplistic conclusions from complex data.

Don’t lose sight of the environment (learning)

There is no question that genetics play a role in shaping human abilities. However, the relative contribution of genes versus environment is notoriously difficult to quantify—particularly in complex traits like language, literacy, and learning.

Consider the case of Mozart, often cited as a quintessential example of innate genius. While he undoubtedly had exceptional natural ability, it is equally true that he was born into a family of musicians, immersed in music from infancy, and received intense, structured training from a very young age. Had he been raised in a home without instruments, exposure, or encouragement, his talents might never have developed—or even been discovered. His story highlights the essential interaction between potential and opportunity.

The work of Shinichi Suzuki in 20th-century Japan offers further insight. Suzuki developed a revolutionary approach to music education based on the idea that musical ability, like language, could be nurtured through early and consistent exposure. His “Talent Education” method involved beginning violin instruction in early childhood—often before age three—and immersing children in music long before they picked up an instrument. Thousands of children trained in his method went on to perform classical concert repertoire with confidence and artistry. Suzuki’s famous assertion, “Talent is not an accident of birth,” reflects his belief that education and environment are the decisive factors in a child’s development.

These examples, while drawn from music, translate well to the world of literacy. Reading is not a biologically programmed skill—it must be explicitly taught, practiced, and reinforced. Even if a child inherits a neurobiological predisposition to struggle with reading (as in dyslexia), the quality of their learning environment—home literacy exposure, early intervention, and effective instruction—can profoundly alter their trajectory.

In other words, genes may set the stage, but experience writes the script.

The Hart and Risley study

Research has shown that the quantity and quality of language young children are exposed to in their early years can have profound and lasting effects on their cognitive and academic development. In a landmark longitudinal study, Hart and Risley (1995) recorded everyday interactions between parents and children across socioeconomic groups. By age three, children from professional families had been exposed to approximately 30 million more words than children from families living in poverty. In addition to hearing more language, these children also received more encouragement, richer vocabulary, and more frequent conversational turns.

Perhaps most striking, early language exposure at age three was a strong predictor of IQ, vocabulary, and reading outcomes in later childhood. Hart and Risley concluded that early linguistic environments lay the foundation for later learning success.

While the study has faced criticism—particularly regarding its small sample size and potential cultural bias—it remains a powerful reminder that language is not just a means of communication; it is also cognitive nourishment. For children at genetic risk for dyslexia, a language-rich environment may not eliminate their underlying predisposition, but it can significantly enhance their resilience and readiness to learn.

High heritability does not mean inescapability

Even if dyslexia is partly inherited—as much of the research suggests—that does not mean it is unchangeable. Genes may influence learning difficulties, but they do not seal a child’s fate. The brain is dynamic, and with the right support, change is possible.

A common misunderstanding about genetic research is the belief that a strong hereditary influence makes a condition permanent or untreatable. In reality, heritability refers to how much of the variation in a trait across a population is due to genetic differences—it does not mean that an individual’s outcome is fixed. As Bishop (2015) notes, discovering that dyslexia has genetic underpinnings should not lead us to lower expectations or reduce support. On the contrary, it highlights the importance of tailoring instruction to meet the specific needs of the learner.

A helpful metaphor is that of a card game. At birth, every child is dealt a hand of cards—their genetic potential. Some hands are more advantageous than others. But as in any game, skill matters. Success comes not only from what one is given but from how one plays. Talent, practice, feedback, and perseverance all contribute to shaping outcomes.

The same is true in learning. A child may inherit a predisposition to reading difficulties. Still, the outcome will depend significantly on their environment—on the quality of instruction, the level of encouragement, and the richness of cognitive stimulation. With appropriate support, many children with dyslexia can become proficient readers and even excel.

Genetics may load the dice, but education helps determine the game.

Edublox specializes in cognitive training and live online tutoring for students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning challenges. We work with families across the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond. Book a free consultation today to explore how we can support your child’s learning journey.

References for Is Dyslexia Genetic? Will My Child Inherit It?:

- Bishop, D. V. M. (2015). The interface between genetics and psychology: Lessons from developmental dyslexia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282(1811).

- Cope, N. A., Harold, D., Hill, G., Moskvina, V., Stevenson, J., Holmans, P. A., … & Williams, J. (2005). Strong evidence that KIAA0319 on chromosome 6p is a susceptibility gene for developmental dyslexia. American Journal of Human Genetics, 76(4), 581–591.

- Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

- DeFries, J. C., & Alarcón, M. (1996). Genetics of specific reading disability. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 2, 39–47.

- DeFries, J. C., Singer, S. M., Foch, T. T., & Lewitter, F. I. (1978). Familial nature of reading disability. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 132(4), 361–7.

- Paracchini, S., Scerri, T., & Monaco, A. P. (2007). The genetic lexicon of dyslexia. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 8, 57–79.

- Scerri, T. S., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2010). Genetics of developmental dyslexia. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(3), 179–197.

- Snowling, M. J., & Melby-Lervåg, M. (2016). Oral language deficits in familial dyslexia: A meta-analysis and review. Psychological Bulletin, 142(5), 498–545.

Is Dyslexia Genetic? Will My Child Inherit It? was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational and reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

Edublox is proud to be a member of the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), a leading organization dedicated to evidence-based research and advocacy for individuals with dyslexia and related learning difficulties.