Vocabulary, phonological awareness, and phonemic awareness are foundational components of early language and literacy development. While each is a distinct skill, research increasingly supports a dynamic, reciprocal relationship among them, particularly during the early years of reading acquisition. Understanding how vocabulary knowledge interacts with phonological and phonemic awareness is key to designing effective literacy interventions and instruction.

Definitions and distinctions

Vocabulary refers to the body of words a person understands and uses. Receptive vocabulary (words understood) typically precedes expressive vocabulary (words used). A rich vocabulary contributes not only to reading comprehension but also to decoding unfamiliar words through contextual cues.

Phonological awareness is the ability to recognize and manipulate the sound structures of language, such as syllables, rhymes, and onset-rime units. Phonemic awareness, a subset of phonological awareness, focuses more narrowly on the recognition and manipulation of individual phonemes—the smallest units of sound in spoken language.

Although vocabulary and phonemic awareness are often taught separately, evidence suggests they are more interconnected than traditionally assumed.

Research evidence of the correlation

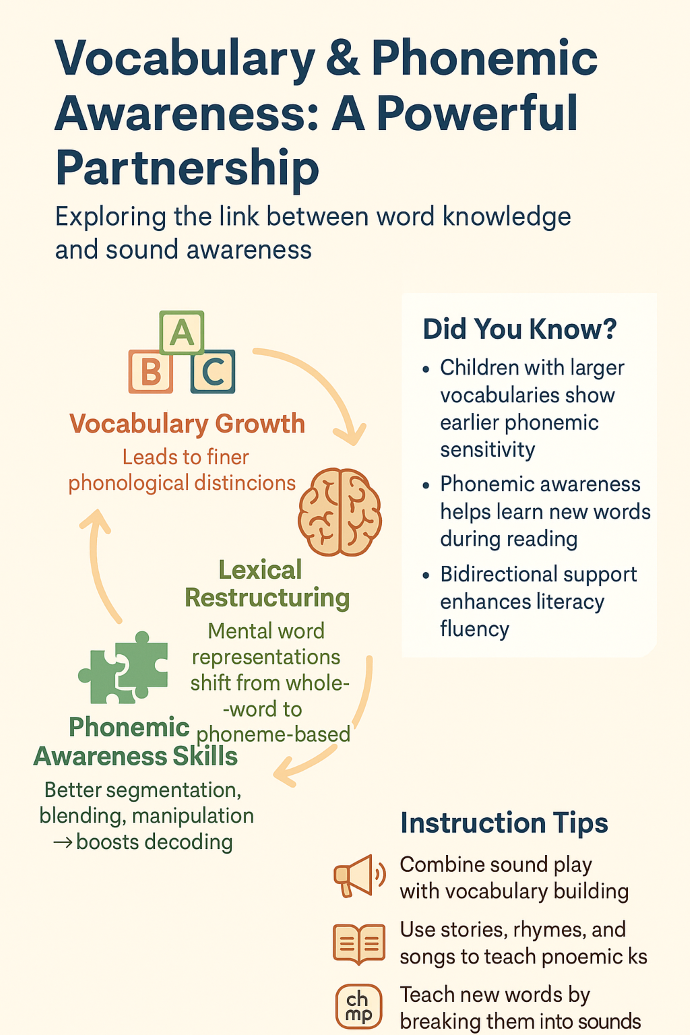

Multiple longitudinal studies reveal a strong correlation between vocabulary development and phonological skills. Children with broader vocabularies tend to outperform peers in phonological awareness tasks. One explanation is that a larger vocabulary encourages the mental organization of words by their phonological properties. For example, children who know many similar-sounding words (e.g., cat, cap, mat, map) are more likely to notice subtle sound distinctions, thereby strengthening phonemic awareness.

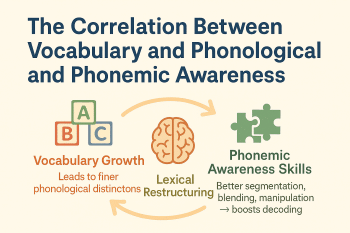

In their seminal work, researchers like Metsala and Walley (1998) proposed the Lexical Restructuring Model to explain this link. According to this model, as children acquire more vocabulary, their mental representations of words become more segmental (i.e., phoneme-based) to allow for fine-grained differentiation. For example, a toddler may initially recognize “dog” holistically, but as their vocabulary grows to include similar words like “dig” or “dot,” they become more attuned to the individual phonemes /d/, /o/, and /g/.

Moreover, studies have shown that deficits in vocabulary can inhibit phonemic awareness development. Children with limited exposure to language—whether due to socioeconomic status, hearing impairment, or other factors—often struggle with phoneme segmentation, blending, and manipulation tasks. Without a strong lexical foundation, it becomes harder to attend to or manipulate the sound structures of language.

Bidirectional influence

The relationship between vocabulary and phonological awareness is not unidirectional. While vocabulary growth fosters phonological sensitivity, developing phonological and phonemic awareness also supports vocabulary acquisition. When children can segment and blend sounds, they are better equipped to decode new words independently, leading to more reading experiences and, subsequently, broader vocabulary exposure.

This bidirectional loop creates a positive feedback cycle: stronger vocabulary improves phonemic awareness, and stronger phonemic awareness facilitates word learning and reading, which in turn expands vocabulary.

Implications for instruction

Understanding this interdependence has important instructional implications:

- Integrated instruction: Instead of isolating phonemic awareness drills from meaning-based vocabulary activities, educators should integrate both. For example, teachers can draw attention to phonemic patterns or rhyme structures while teaching new words.

- Context-rich phonemic activities: Phonemic awareness is more effective when embedded in meaningful contexts, such as storytelling, songs, or thematic units, rather than isolated syllable or phoneme games.

- Targeted interventions: For children with delays in either area, interventions should address both simultaneously. For instance, introducing new vocabulary alongside phoneme manipulation exercises (e.g., “What sound do you hear at the beginning of chimpanzee?”) reinforces learning.

Conclusion

Vocabulary and phonological/phonemic awareness are intricately connected. Vocabulary development sharpens phonemic representations by increasing the need to differentiate between similar-sounding words. Conversely, strong phonological skills empower children to decode unfamiliar words and broaden their vocabulary. Recognizing and leveraging this correlation in educational practice can significantly enhance early literacy outcomes and prevent reading difficulties.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning disabilities. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

References:

- McDowell, K., Carroll, J., & Ziolkowski, R. (2013). Relations between phonological awareness and vocabulary in preschoolers. International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science, 1(2), 75–84.

- Metsala, J. L., & Walley, A. C. (1998). “Spoken vocabulary growth and the segmental restructuring of lexical representations: Precursors to phonemic awareness and early reading ability.” In J. L. Metsala & L. C. Ehri (Eds.), Word Recognition in Beginning Literacy (pp. 89–120). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Moats, L., & Tolman, C. (2009). Why phonological awareness is important for reading and spelling. Reading Rockets.

- Purwati, H. (2022). The effect of vocabulary and phonological awareness on students’ reading comprehension. SALEE: Study of Applied Linguistics and English Education, 3(2), 170–183.

Correlation Between Vocabulary and Phonological and Phonemic Awareness was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational and reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.