Over the past several decades, our understanding of dyslexia has advanced significantly. No longer viewed as a singular condition, dyslexia is now recognized as a heterogeneous learning disorder with multiple subtypes. One of the most extensively studied—and arguably the most challenging—is double deficit dyslexia, a term introduced by Maryanne Wolf and Patricia Bowers (1999). This subtype is marked by impairments in both phonological processing and rapid automatized naming (RAN), and it is associated with more severe and persistent reading difficulties than other forms of dyslexia.

.

Table of contents:

- Beyond phonological awareness

- The science behind double deficit dyslexia

- Symptoms of double deficit dyslexia

- How common is double deficit dyslexia?

- Diagnosis, intervention, and prognosis

- Double deficit dyslexia case studies

- Conclusion

.

Beyond phonological awareness

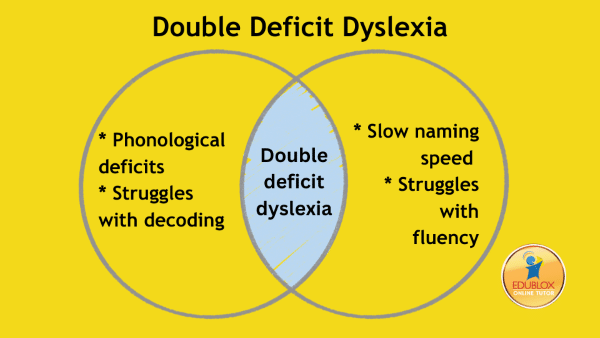

Dyslexia has traditionally been linked to phonological deficits—difficulties recognizing and manipulating the sound structures of language. Phonological awareness is essential for decoding, spelling, and developing reading fluency. Targeted interventions, especially systematic phonics instruction, have helped many children overcome these challenges — but not all.

However, some children continued to struggle even after receiving high-quality phonological training. Their reading difficulties persisted despite appropriate teaching. This pattern led researchers to look deeper, and they identified a second core weakness: rapid automatized naming (RAN)—the ability to quickly and effortlessly name familiar visual stimuli like letters, numbers, or colors. RAN isn’t about knowing the word; it’s about retrieving it automatically and at speed—a skill that relies on efficient access to memory, attention, and processing.

In response, Wolf and Bowers (1999) introduced the double deficit hypothesis. They proposed that while some children show weaknesses in phonological awareness and others in RAN, those with deficits in both experience the most profound and persistent reading difficulties.

The science behind double deficit dyslexia

Functional neuroimaging studies (e.g., Shaywitz et al., 2003) have revealed that individuals with double deficits show reduced activation across several key brain areas. These include regions responsible for phonological decoding, such as the left inferior frontal gyrus and the temporoparietal cortex, as well as areas involved in rapid visual processing, like the occipitotemporal region. This widespread underactivation helps explain their dual difficulties with both reading accuracy and fluency.

In support of this, research has consistently shown that children with double deficits:

- Perform significantly worse on tasks measuring reading fluency and accuracy compared to peers with only one deficit (Wolf et al., 2002).

- Respond poorly to phonics-based instruction alone (Torgesen et al., 2001).

- Typically, more intensive, longer-lasting interventions are needed to achieve measurable progress.

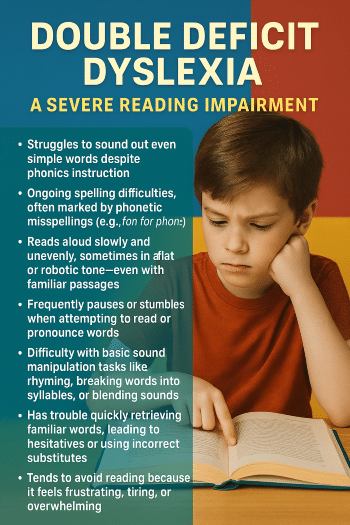

Symptoms of double deficit dyslexia

Because it affects multiple core reading skills, double deficit dyslexia can manifest in a variety of ways. While each learner is different, common signs include:

- Difficulty sounding out even simple words despite phonics instruction.

- Persistent spelling challenges, often with phonetic errors (e.g., fon for phone).

- Slow, effortful reading aloud—often marked by choppy pacing or a flat, robotic tone.

- Frequent hesitations or stumbling when attempting to pronounce words.

- Struggles with phonological tasks like rhyming, segmenting syllables, or blending sounds.

- Trouble rapidly retrieving familiar words, leading to delays or incorrect substitutions.

- Avoidance of reading due to frustration, fatigue, or low confidence.

- Poor comprehension, as most cognitive energy is spent on decoding rather than understanding.

How common is double deficit dyslexia?

In a 2000 study, Lovett and colleagues examined 166 children aged 7 to 13 who were experiencing significant reading difficulties. They aimed to explore how these difficulties aligned with deficits in phonological processing, rapid naming, or both.

After analyzing usable data from 140 participants (84% of the sample), the researchers found that more than half (54%) showed deficits in both phonological awareness and naming speed—placing them in the double deficit category. Another 24% exhibited only a naming-speed deficit, while 22% had a phonological deficit alone. Notably, children with double deficits demonstrated more severe reading impairments than those with just one type of difficulty.

However, not all researchers agree that double deficit dyslexia represents a distinct subtype. Some argue that naming-speed difficulties may stem from underlying phonological weaknesses rather than constituting a separate core deficit. According to this view, the ability to quickly name familiar visual items relies heavily on efficient access to phonological information—which may already be compromised in dyslexia (Vaessen et al., 2009).

Diagnosis, intervention, and prognosis

Formal identification typically involves standardized assessments of both phonological processing and rapid automatized naming (RAN). These diagnostic tools help distinguish between single- and double-deficit profiles—an essential step in crafting effective, individualized interventions.

Given its complexity, double deficit dyslexia requires a multifaceted intervention strategy. Successful programs must simultaneously target:

- Phonological weaknesses using explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, decoding techniques, and orthographic mapping.

- Naming speed through repeated reading, fluency drills, and timed naming exercises that build automaticity.

- Underlying cognitive skills, such as working memory and attention, support the development of decoding accuracy and reading fluency.

While the research can feel overwhelming, it’s important to remember that children with double deficit dyslexia can make meaningful and lasting progress. Success depends on early identification and a carefully designed intervention—one that goes beyond traditional reading instruction to also strengthen the cognitive foundations that support fluent, accurate reading. Cristiano’s story offers a compelling example of what’s possible when the right approach meets the right need.

Double deficit dyslexia case studies

Cristiano

Cristiano, bright and creative, struggled with reading. Despite his intelligence and strong comprehension skills, he found it incredibly difficult to read fluently, recognize common words, or spell accurately. Words just didn’t “stick.” Reading aloud was painfully slow and halting. Over time, frustration turned into discouragement, and discouragement into self-doubt.

A comprehensive neurocognitive evaluation revealed the reason: Cristiano had double deficit dyslexia—a combination of phonological processing and rapid naming difficulties. This dual challenge explained not only his difficulties with sounding out unfamiliar words but also his slow and effortful pace, even when reading simple text.

Cristiano’s breakthrough came when he began a structured program that paired research and evidence-based reading instruction with targeted cognitive training. His intervention plan focused on building attention, phonological skills, processing speed, memory, decoding and fluency. Gradually, his reading became smoother—and his confidence began to grow. Watch this video to see how this integrated approach transformed Cristiano’s reading journey.

Maddie

Maddie was also diagnosed with double-deficit dyslexia. She scored in the 1st percentile for reading—the lowest possible—meaning that 99% of children her age were reading better than she could. Her scores were equally concerning in related skills: 6th percentile for phonological awareness, 16th for phonological memory, and below the 1st percentile for rapid naming.

Professionals who evaluated Maddie were struck by the severity of her difficulties. More than one told her parents she would probably never learn to read. Her mother, however, refused to accept this and began a determined search for effective help.

After many approaches failed, Maddie began a nine-month program with Edublox. A follow-up assessment by her psychologist revealed significant gains: phonological awareness improved from the 6th to the 39th percentile, phonological memory from the 16th to the 30th, and rapid naming from below the 1st to the 8th. On the STAR Reading Test, her reading jumped by 54 percentile points. Watch their journey in the video below.

Conclusion

Double deficit dyslexia represents one of the most challenging reading profiles encountered in educational and clinical settings. It reflects the convergence of two distinct processing difficulties—each demanding in isolation but particularly debilitating when combined.

Fortunately, decades of research have moved us beyond one-size-fits-all solutions. We now know that phonological training alone is insufficient. To truly help students with double deficits thrive, we must adopt a dual-focus approach—integrating phonics, fluency-building, naming speed training, and cognitive support. With the right tools and early intervention, even the most persistent reading difficulties can be transformed into lasting progress.

At Edublox, we specialize in cognitive training and reading intervention tailored for children with double deficit dyslexia. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

References for Double Deficit Dyslexia: A Severe Reading Impairment:

- Bowers, P. G., & Wolf, M. (1993). Theoretical links among naming speed, precise timing mechanisms and orthographic skill in dyslexia. Reading and Writing, 5(1), 69–85.

- Lovett, M. W., Steinbach, K. A., & Frijters, J. C. (2000). Remediating the core deficits of developmental reading disability: A double-deficit perspective. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33(4), 334–358.

- Shaywitz, S. E., Shaywitz, B. A., Pugh, K. R., Fulbright, R. K., Constable, R. T., Mencl, W. E., … & Gore, J. C. (2003). The neurobiology of reading and reading disability (dyslexia). In M. S. Gazzaniga (Ed.), The cognitive neurosciences (3rd ed., pp. 865–876). MIT Press.

- Torgesen, J. K., Alexander, A. W., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Voeller, K. K. S., & Conway, T. (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: Immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34(1), 33–58.

- Vaessen, A., Gerretsen, P., & Blomert, L. (2009). Naming problems do not reflect a second independent core deficit in dyslexia: double deficits explored. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 103(2), 202–221.

- Wolf, M., & Bowers, P. G. (1999). The double-deficit hypothesis for the developmental dyslexias. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 415–438.

- Wolf, M., Bowers, P. G., & Biddle, K. (2000). Naming-speed processes, timing, and reading: A conceptual review. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33(4), 387–407.

Double Deficit Dyslexia: A Severe Reading Impairment was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyslexia specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

Edublox is proud to be a member of the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), a leading organization dedicated to evidence-based research and advocacy for individuals with dyslexia and related learning difficulties.