Geometry is not just another chapter in a math textbook; it is a way of seeing the world. It is the silent architecture behind art, engineering, nature, and even thought itself. From the pyramids of Egypt to the orbits of planets, from the brushstrokes of da Vinci to the code powering self-driving cars, geometry is the language of space and structure.

As one of the oldest branches of mathematics, geometry bridges the gap between abstraction and reality. It unites precision with beauty, theory with application. It trains us to reason clearly, imagine boldly, and solve problems that reach from the classroom to the cosmos.

This article explores what geometry is, its core branches, why it matters, and how both students and teachers can unlock its full potential.

What is geometry?

The word geometry comes from the Greek geo (earth) and metron (measure), born out of land-surveying needs thousands of years ago. Today, it encompasses the study of shapes, sizes, positions, and dimensions, as well as how they transform or relate to one another.

Geometry asks timeless questions:

- How do we measure the shortest path between two points?

- How can we calculate the area of a field or the volume of a cylinder?

- What happens when a shape is reflected, rotated, or stretched?

.

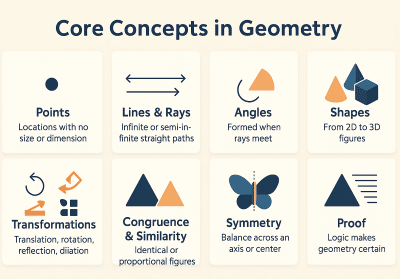

Its basic building blocks are deceptively simple:

- Points: locations with no size or dimension.

- Lines and rays: infinite or semi-infinite straight paths.

- Angles: formed when rays meet.

- Shapes: from triangles and circles to cubes and cones.

- Transformations: translations, rotations, reflections, dilations.

- Congruence and similarity: figures that are identical or proportional.

- Symmetry: balance across an axis or center.

- Proof: the logic that makes geometry not guesswork but certainty.

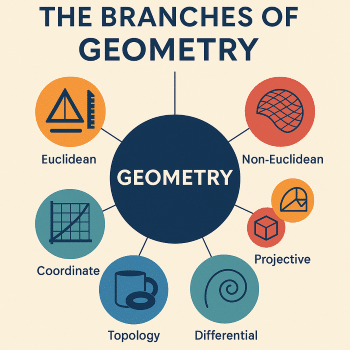

The branches of geometry

Euclidean geometry

The geometry of flat surfaces, Euclidean geometry, was first formalized around 300 BCE by the Greek mathematician Euclid in his seminal work Elements. His five postulates (axioms) formed the foundation of mathematics for nearly two millennia. This is the geometry most people encounter in school — triangles with 180° angles, parallel lines that never meet, and circles defined by constant radii.

Euclidean geometry is far from outdated. Its principles are vital in:

- Architecture and construction: ensuring that walls meet at right angles and arches are stable.

- Surveying and cartography: calculating land boundaries and plotting maps.

- Design and engineering: from carpentry and drafting to mechanical parts and bridge layouts.

In essence, Euclidean geometry is the mathematics of the physical world we inhabit daily.

Coordinate (analytic) geometry

In the 17th century, René Descartes revolutionized geometry by introducing the Cartesian coordinate system. Suddenly, geometry could be expressed with equations and graphs — lines became algebraic formulas (y = mx + b), and circles or parabolas could be described precisely with coordinates. This fusion of algebra and geometry opened the door to modern science.

Applications include:

- Computer-aided design (CAD): used by engineers, architects, and product designers.

- Physics: modeling trajectories, forces, and fields.

- Economics: graphing supply-and-demand curves.

- Geographic information systems (GIS): mapping everything from city layouts to climate zones.

Coordinate geometry turned geometry into a tool for calculation, prediction, and technological progress.

Non-euclidean geometry

For centuries, Euclid’s fifth postulate (the parallel postulate) was a sticking point for mathematicians. In the 19th century, rejecting or modifying it gave birth to non-Euclidean geometries:

- Hyperbolic geometry: In negatively curved space, through a point outside a line, infinitely many parallels can exist. Picture a saddle-shaped surface extending forever.

- Elliptic geometry: In positively curved space (like a sphere), parallel lines do not exist; they eventually intersect.

.

These breakthroughs reshaped modern science and philosophy. They became the mathematical backbone of Einstein’s general relativity, explaining how space-time curves under gravity, how light bends around stars, and why the universe expands. Without non-Euclidean geometry, much of astrophysics would remain a mystery.

Projective geometry

In projective geometry, distances and angles don’t matter — only alignment and perspective do. A circle might project as an ellipse, but the relationship between points, lines, and planes is preserved.

This branch became crucial during the Renaissance, when artists like Brunelleschi and da Vinci experimented with perspective drawing. Today, it remains indispensable in:

- Computer graphics and vision: rendering 3D worlds on 2D screens.

- Architecture: creating accurate blueprints and perspective views.

- Photography and camera calibration: understanding how lenses distort reality.

Projective geometry highlights the artistic side of mathematics, showing that geometry is not only about measurement but also about perception.

Differential geometry

When calculus met geometry, a new branch was born. Differential geometry studies curves, surfaces, and their properties using tools from calculus and linear algebra. It allows mathematicians to measure curvature, torsion, and geodesics (the shortest paths on curved surfaces).

Its applications are profound:

- Engineering: designing airplane wings or car bodies with minimal drag.

- Medicine: modeling protein folding and biological membranes.

- Technology: GPS systems, which correct for relativity effects on satellite orbits.

- Physics: describing the warped fabric of space-time in Einstein’s relativity.

Without differential geometry, we couldn’t explain gravity as curvature, predict black holes, or design modern spacecraft.

Topology

Topology, sometimes playfully called “rubber-sheet geometry,” is the study of properties that remain unchanged under stretching, twisting, or bending — but not tearing. To a topologist, a coffee mug and a donut are the same because each has one hole.

Topology has grown into one of the most abstract yet powerful areas of modern mathematics. It underlies:

- Neuroscience: modeling the brain as a complex network.

- Quantum computing: designing error-resistant systems.

- Data science: studying the “shape” of massive datasets.

- Physics: understanding particle interactions and knot theory in string theory.

Topology pushes geometry beyond measurement into the essence of form and structure.

✨ Together, these branches illustrate geometry’s journey: from Euclid’s flat world, through Descartes’ coordinates, into curved universes, visual perspectives, dynamic curves, and abstract topological spaces. Geometry has grown from practical land measurement into a mathematical philosophy that underpins science, art, and technology.

Why geometry matters

Geometry is not just a subject to be passed in school; it is a way of thinking that extends into daily life and careers. By learning geometry, students build skills in logic, visualization, and problem-solving that transfer far beyond the classroom.

In daily life, geometry shows up when we:

- Navigate with GPS and maps.

- Arrange furniture in a room or design a garden layout.

- Appreciate patterns in art, architecture, and nature.

- Understand sports strategies and angles of play.

In careers, geometry is foundational for:

- Engineering and architecture – designing buildings, bridges, and machines.

- Medicine – interpreting scans, modeling organs, and performing surgeries with precision.

- Technology and AI – powering computer graphics, robotics, and self-driving cars.

- Astronomy and physics – describing planetary orbits, cosmic structures, and space-time.

- Art and design – applying symmetry, perspective, and proportion in visual creativity.

Geometry matters because it equips students to reason, imagine, and build. It is both a practical toolkit and a doorway into some of the most exciting fields of human endeavor.

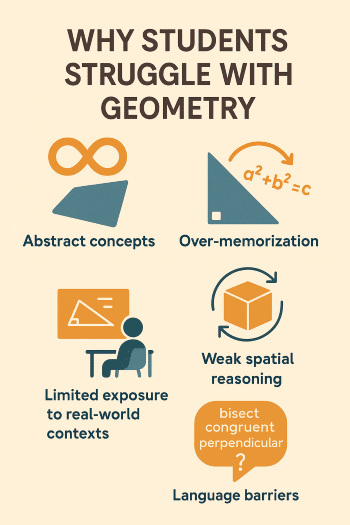

Why students struggle with geometry

Despite its visual appeal and real-world relevance, many students face challenges when learning geometry. Understanding these difficulties is the first step in addressing them effectively.

- Abstract concepts: Many geometric ideas — like infinite lines, undefined terms, and higher-dimensional shapes — can be hard to visualize or mentally process. Students who prefer concrete, hands-on experiences may find these abstractions especially difficult.

- Over-memorization: A common misconception is that geometry is only about memorizing theorems and formulas. Without grasping the underlying reasoning, students struggle to apply what they’ve memorized when faced with unfamiliar problems.

- Weak spatial reasoning: Not all learners naturally excel at visualizing shapes in space. Tasks such as imagining how a cube unfolds into a net, or how a triangle rotates around an axis, require guided practice to build this skill.

- Limited exposure to real-world contexts: When geometry is taught in isolation from everyday life — as symbols on a board rather than the shapes in bridges, buildings, or art — students fail to see its relevance, and their motivation drops.

- Language barriers: Geometry comes with a specialized vocabulary (e.g., bisect, congruent, perpendicular) that can be confusing if not explicitly taught and reinforced. The language can become a stumbling block before the concepts even have a chance to take root.

How to excel at geometry

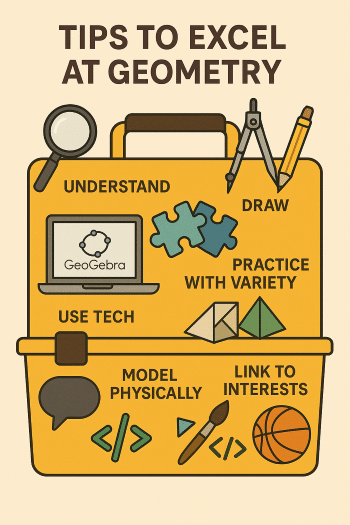

Succeeding in geometry isn’t about memorizing endless formulas — it’s about learning how to think, see, and apply ideas in new ways. The subject rewards curiosity, persistence, and creativity just as much as calculation. With the proper habits, students can build confidence and discover that geometry is not only manageable but also helpful and even enjoyable.

Practical help students:

Geometry can feel challenging at first, but with the proper habits and tools, success is within reach. Here are strategies that work:

- Understand, don’t just memorize: Learn why a theorem works, not only how to apply it.

- Draw everything: Sketching a problem often makes the solution visible.

- Practice with purpose: Combine repetition with varied problem types to build real flexibility.

- Use digital tools: Apps like GeoGebra bring geometry to life by animating and exploring relationships.

- Build and manipulate models: Use paper, string, or 3D objects to grasp complex ideas.

- Ask questions: Never hesitate to question definitions, theorems, or solutions — curiosity drives deeper learning.

- Teach others: Explaining geometry to a peer or parent reinforces your own understanding.

- Link geometry to your interests: Connect it to what you love — art, sports, coding, or design — and it will feel more relevant.

.

Practical help for parents:

Parents play a key role in making geometry less intimidating and more meaningful at home. Here are ways to support your child:

- Stay positive about math: A parent’s attitude shapes a child’s mindset — avoid “I was bad at math” talk and focus on growth.

- Spot shapes in daily life: Point out triangles in roofs, circles in wheels, or symmetry in logos.

- Connect with play: Use puzzles, tangrams, or building toys like LEGO to strengthen spatial reasoning.

- Talk angles and directions: Use a clock face, sports moves, or even dance steps to show angles and rotations.

- Use cooking and crafts: Cutting pizzas, folding paper, or quilting patterns all illustrate geometric concepts.

- Encourage drawing and sketching: Even rough diagrams help children visualize and problem-solve.

- Translate the language: Break down tricky words (congruent, parallel, bisect) into everyday language.

- Celebrate effort, not just accuracy: Praise persistence and creativity as much as getting the correct answer.

.

Practical help for teachers:

Teaching geometry effectively means going beyond the textbook. Here are proven strategies to make lessons more engaging and accessible:

- Start with the tangible: Use physical objects and manipulatives before moving to abstract ideas. Paper folding, geoboards, and compasses are excellent tools.

- Use real-world problems: Connect geometry to contexts like floor plans, sports statistics, or city mapping.

- Incorporate technology: Bring concepts to life with dynamic geometry software, simulations, and videos that demonstrate transformations and theorems.

- Encourage exploration: Allow students to discover geometric relationships on their own through guided investigations.

- Differentiate instruction: Adapt lessons to fit different learning styles and abilities—visual, kinesthetic, logical, and verbal.

- Celebrate creativity and logic: Recognize both the problem-solver and the designer; geometry is both art and science.

- Anchor new vocabulary visually: Post words like parallel, congruent, and bisect on classroom walls with simple diagrams so students internalize the terms.

- Do a 5-minute “spatial warm-up”: Start lessons with a quick puzzle, fold, or sketching task to get students’ spatial reasoning engaged.

- Model problem-solving: Work through examples aloud, showing not just the answer but the reasoning steps.

- Use mistakes as tools: Present incorrect diagrams or flawed proofs and let students “debug” them — this builds confidence and logical reasoning.

.

Closing reflection

Geometry does more than measure space; it enlarges the mind. It is at once practical and poetic, ancient and futuristic. It teaches us not only how to calculate angles or volumes but also how to reason, design, and imagine worlds not yet built.

“Geometry is not the study of shapes alone. It is the training of the mind to see patterns, balance, and possibility — and to build the future one angle at a time.”