Table of contents:

- What is auditory dyslexia?

- Symptoms and characteristics

- Causes of auditory dyslexia

- Treatment of auditory dyslexia

What is auditory dyslexia?

The term dyslexia was coined from the Greek words dys, meaning ill or difficult, and lexis, meaning word. It is used to refer to persons for whom reading is simply beyond their reach. Spelling and writing are usually included due to their close relationship with reading.

According to popular belief, dyslexia is a neurological disorder in the brain that causes information to be processed and interpreted differently, resulting in reading difficulties.

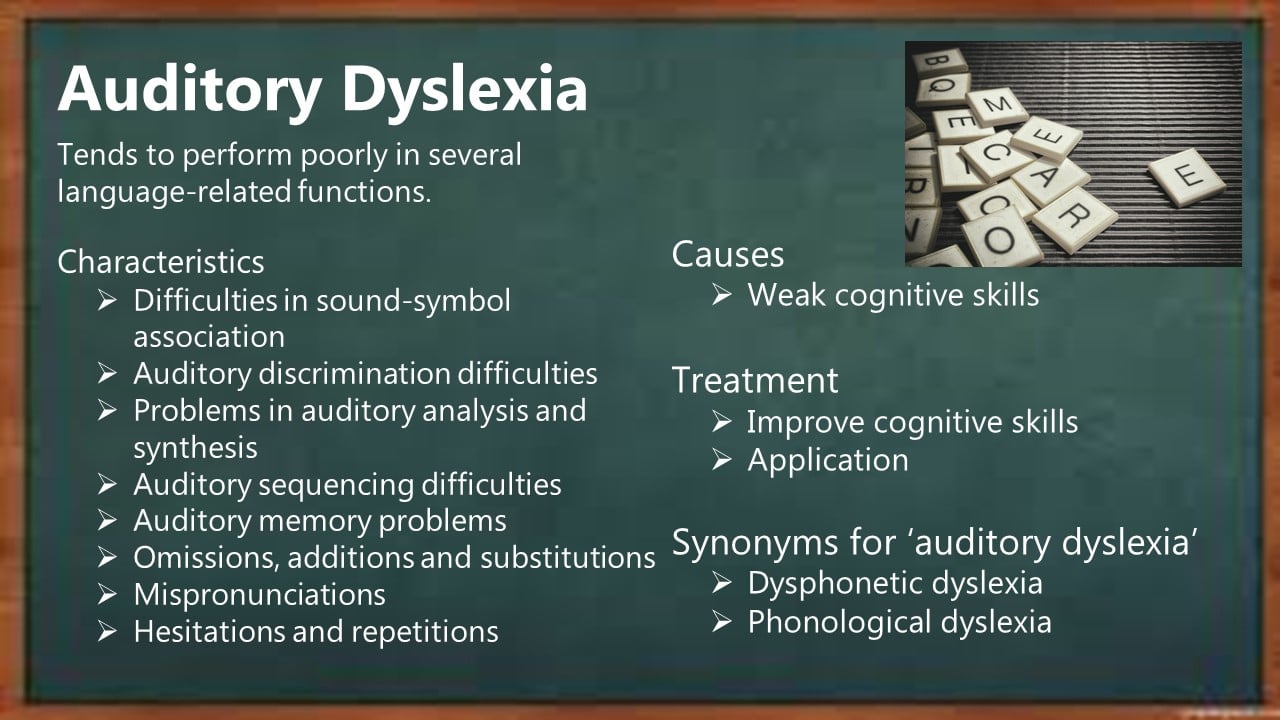

The terms auditory dyslexia and visual dyslexia are often used by scholars to describe two main types of dyslexia. Auditory dyslexia — also called dysphonetic dyslexia or phonological dyslexia — is a subtype of dyslexia that refers to children who struggle with reading because they have problems processing the basic sounds of language (phonemes), sounds of letters, and groups of letters.

Symptoms and characteristics

Among the manifestations that characterize auditory dyslexia, according to Saroj D. Sutaria (Specific Learning Disabilities: Nature and Needs), are difficulties in sound-symbol association; auditory discrimination difficulties; problems in auditory analysis and synthesis; auditory sequencing difficulties; auditory memory problems; omissions, additions and substitutions; mispronunciations; and hesitations and repetitions.

1.) Sound-symbol association problems

Johnson and Myklebust described dyslexia as a breakdown in inter-neurosensory processing. This means the child cannot make the association needed between the graphemes and their phonemes.

The child’s most significant difficulty lies in comprehending that although the English alphabet consists of only 26 letters, there are 44 phonemes; that the names of the letters are different from their phonemic properties; that few letters have only one sound which remains constant; that combinations of certain consonants and vowels produce entirely different sounds; that certain consonant-vowel combinations change the sound; that there are hard, soft and silent sounds depending on the positioning of the letters in words, etc.

The difficulty is compounded when the child also has a memory disorder.

2.) Auditory discrimination difficulties

The child has difficulty differentiating between similarities and differences in the sounds of letters and words. This problem is aggravated when the child cannot sort through or ignore background noises and voices.

The most apparent difficulties are in certain consonantal sounds, such as /b/ and /p/, /m/ and /n/ or /d/ and /t/, etc. Even more challenging are short vowel sounds, especially /e/ and /i/. Words frequently misread are three-letter words in which only the vowel sound is different, for example, /pen/ and /pin/.

Critchley noted that the reading-disabled child cannot detect differences in the auditory properties of letters and words.

3.) Difficulties in auditory analysis and synthesis

Reading-disabled children cannot read unfamiliar words because they lack the structural analytical approach necessary for this task. Structural analysis requires identifying morphemes, including prefixes, suffixes, root words, and the like. After identifying these smaller units, they must be blended as a whole.

Critchley observed the child tends to guess wildly at words, usually done based on the first letter and sometimes on length.

4.) Auditory sequencing difficulties

The temporal order of sounds in words is disturbed. The child is unable to retain in short-term memory store the sequence of sounds long enough to reproduce them in the correct order when reading out loud. Thus, while the individual letters may be associated with their sounds correctly and syllables identified accurately, when it comes time to pronounce them together, the child reverts the order, for instance, /emeny/ in place of /enemy/.

Senf reported evidence of this in the reading disabled, whose primary problems may be in word mixing in compound words, for example, /mindwill/ instead of /windmill/, /shoehorse/ for /horseshoe/, etc.

Denckla observed that children with this type of problem tend to change with age from having issues in both reading and spelling to spelling alone. However, they might continue to have difficulty with the phonetic aspects of a foreign language.

5.) Auditory memory problems

Retrieval of sounds of letters and words for spontaneous use may be complex for the auditory dyslexic because of an inefficient system of processing in long-term memory storage.

The difficulty in recalling specific sounds and names may account for certain substitutions that the reading disabled makes, for example, /dad/ for /father/ or /baby/ for /daughter/. Not only are the substituted words easier to pronounce but their pronunciation is based on regular phonics principles, while the others are not. Pronunciation of words like /father/, /daughter/, etc. requires the child to remember the irregularities in making symbol-sound associations.

6.) Omissions, additions, substitutions

The reading disabled tends to omit single phonemes or syllables in word pronunciation. Thus /walking/ may be read as /walk/, /boxes/ as /box/, /rust/ as /rut/, /bent/ as /bet/, etc. While the first two types may not significantly affect the meaning derived from the content, the remaining two would render the statement meaningless. Sometimes, whole words may be omitted. Although whole-word omissions usually result from visual oversight, the anticipation of difficulties in pronouncing a particular word may cause the child to ignore it.

Wiig and Semel reported that words beginning with /s/ blends tend to cause some reading disabled to omit some sound units in words, for example, /spit/, /sit/ for /split/, while in others to add sounds, for example, /split/ or /slit/ for /sit/.

Some children add words or sound units, for example, /the little baby/ in place of /the baby/ or /baby sister/ instead of /babysitter/, etc. Frequently heard phrases that become automatically associated with each other tend to be added more often than others, such as /Once upon a time there was/ in place of /Once there was/, etc.

As for substitutions, we have already noted one type under memory problems. These are meaningful substitutions because their use does not significantly alter the text’s meaning. Other substitutions, however, may change or distort the meaning.

Mattis suggested that some substituted words may sound like the correct words but are not. For example, the child may read /hijackers/ instead of /hitchhikers/ or /optimist/ for /optometrist/, etc.

7.) Mispronunciations

A variety of mispronunciations occur in the auditory dyslexic. Critchley noted incorrect pronunciation of vowels. Already mentioned is the difficulty that the child has with short vowels. The child may not fully comprehend the difference between short and long vowel sounds, thus confusing, for example, /mat/ and /mate/, /hat/ and /hate/.

The variations in sounds that certain words produce are especially baffling for this child. For instance, except for their initial consonant sounds, the words /hut/ and /put/ have identical properties, yet the pronunciation of the two words’ vowels are entirely different. Similarly, in /have/, /save/, and /gave/, the initial consonants are different, and the rest is the same in all three words, yet the pronunciation is different in the first while the other two rhyme.

Other mispronunciations may affect initial, medial, or final sounds of individual consonants or consonant blends, digraphs, or diphthongs. Wiig and Semel noted difficulties with blending when /l/, /w/, or /r/ are in the second position. Insertions of extra sounds produce mispronunciations, as in /trick/ for /tick/, just as omissions do. Incorrect stress on syllables in words may also produce mispronunciation.

8.) Hesitations and repetitions

Uncertainty about the correct pronunciation of a word often causes the child to pause incorrectly between words or to exhibit perseverative tendencies; that is, the child will repeat the preceding phrase or word several times before attempting the problem word.

Causes of auditory dyslexia

To understand what causes auditory dyslexia, we must focus on the cognitive skills underpinning language-related functions. Cognitive skills of importance include phonological awareness and verbal short-term memory.

1.) Phonological awareness

Phonological awareness refers to an individual’s awareness of a language’s phonological or sound structure. It is a listening skill that includes distinguishing speech units, such as rhymes, syllables in words, and individual phonemes in syllables.

Phonemic awareness is a subset of phonological awareness that focuses on recognizing and manipulating phonemes, the smallest units of sound. The two most crucial phonemic awareness skills are segmenting and blending. Segmenting is breaking a word apart into its individual sounds. Blending is saying a word after each of its sounds is heard. If a child can segment, they can say f-i-sh after hearing the word fish. If they can blend, they can say the word fish after hearing the individual sounds f-i-sh. Phonemic awareness is said to be a foundational skill for phonics, which in turn is the foundation for reading.

2.) Verbal short-term memory

Verbal memory involves the recall of words or verbal items. Verbal short-term memory is considered a type of short-term memory that reflects the ability to hold information as “active” or available in one’s mind for a brief amount of time.

Verbal short-term memory involves capacity, duration, and encoding. Capacity refers to the amount of information a person can hold in their memory. Duration refers to how long a person can retain the information in their memory. Encoding is a technique used to retain information and may include mental or verbal rehearsal and repetition of the items.

Treatment of auditory dyslexia

The good news is that weaknesses in cognitive skills can be attacked head-on; it is possible to strengthen these mental skills through training and practice. Edublox aims at strengthening underlying cognitive skills, including phonemic awareness and verbal short-term memory. In addition, children’s reading and spelling deficits are addressed during live online lessons. Click here to book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Watch this playlist of customer reviews and experience how Edublox training and tutoring help turn dyslexia around.

Auditory dyslexia – key takeaways

Authored by Susan du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years’ experience in learning disabilities.