Table of contents:

- What is dyseidetic dyslexia?

- Symptoms of dyseidetic dyslexia

- Cause of dyseidetic dyslexia

- Treatment of dyseidetic dyslexia

What is dyseidetic dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a difficulty in learning to decode (read aloud) and to spell. Dyslexia is a common concern as it affects many children and adults, and although no two dyslexics have the same symptoms, there are key symptoms that one can quite easily pick up.

Reading difficulties related to visual-processing weaknesses have been called dyseidetic dyslexia, orthographic dyslexia, or surface dyslexia. Visual processing is the ability to interpret visual stimuli or, more simply, to understand what one sees.

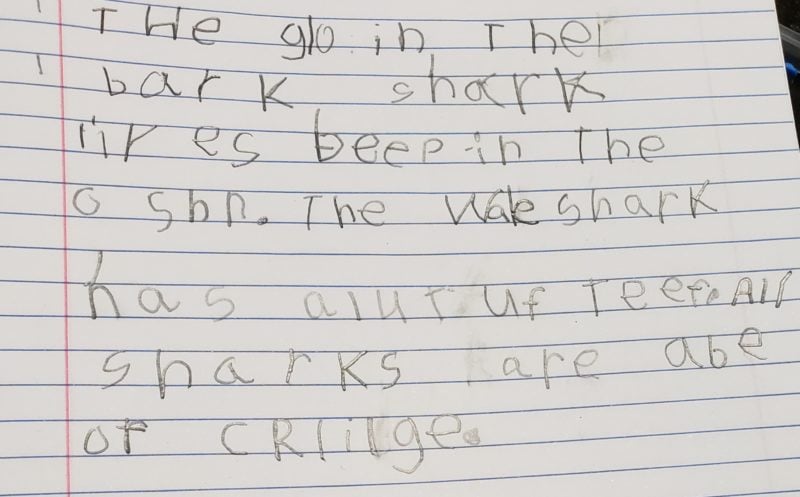

The primary deficit of dyseidetic dyslexia is the inability to revisualize the gestalt of words. A child with dyseidetic dyslexia generally has a good grasp of phonetic concepts. Usually, they have little difficulty spelling words which may be long and phonetically regular, but small and irregular nonphonetic words, such as what, the, talk, and does create great difficulty. They have limited sight vocabulary; many words must be sounded out laboriously, as though being seen for the first time. They seem to attend only to partial cues in words, overlooking a systematic analysis of English orthography.

Symptoms of dyseidetic dyslexia

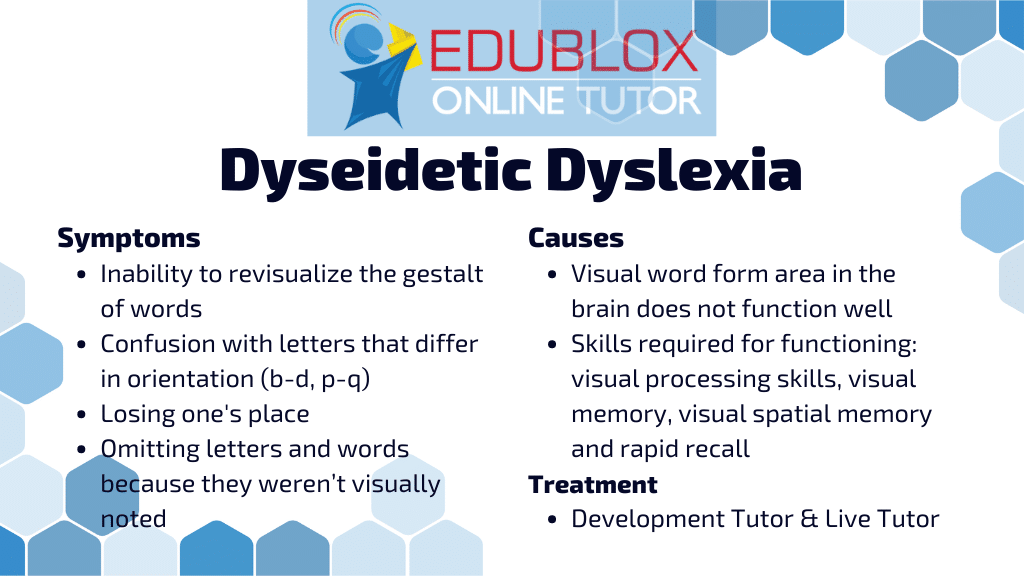

Corinne Roth Smith lists other reading and spelling patterns of children with dyseidetic dyslexia:

- Confusion with letters that differ in orientation (b-d, p-q).

- Confusion with words that can be dynamically reversed (was-saw).

- Losing the place because one does not instantly recognize what had already been read, as when switching one’s gaze from the right side of one line to the left side of the next line.

- Omitting letters and words because they weren’t visually noted.

- Masking the image of one letter by moving the eye too rapidly to the subsequent letter may result in the omission of the first letter.

- Difficulty with rapid retrieval of words due to visual retrieval weaknesses.

- Visual stimuli in reading prove so confusing that it is easier for the child to learn to read by first spelling the words orally and then putting them in print.

- Difficulty recalling the shape of a letter when writing.

- Spells phonetically but not bizarrely (laf-laugh; bisnis-business).

- Can spell difficult phonetic words but not simple irregular words.

.

Cause of dyseidetic dyslexia

Two separate regions of the brain are involved in reading: one in sounding out words and the other in seeing words as pictures. The latter is known as the visual word form area (VWFA). It functions separately from the area that processes written word sounds and is critically involved in visual word recognition. The VWFA is most likely underdeveloped in people with dyseidetic dyslexia; therefore, this part of the brain must be targeted in treatment.

Neuroscientists at Georgetown University Medical Center (2016) concluded that skilled readers can recognize words at lightning-fast speed when they read because the words have been placed in the VWFA.

Glezer and her coauthors tested word recognition in 27 volunteers in two different experiments using fMRI. First, the researchers saw that words that were different but sound the same — like ‘hare’ and ‘hair’ — activate different neurons, akin to accessing different entries in a dictionary’s catalog. If the sounds of the word influenced this part of the brain, one would expect to see that they activate the same or similar neurons, but this was not the case — ‘hair’ and ‘hare’ looked just as different as ‘hair’ and ‘soup.’

In addition, the researchers found a distinct region sensitive to sounds, where ‘hair’ and ‘hare’ looked the same. The researchers thus showed that the brain has regions that specialize in doing each of the components of reading: one is doing the visual piece, and the other is doing the sound piece.

In the most extensive study of its kind up to date, Brem et al. (2020) confirmed that the VWFA is critical to fluent reading using fMRI data (n = 140 children, 7.9–12.2 years; 55 children with dyslexia, 73 typical readers, 12 intermediate readers). Their study also showed that connectivity of the left occipitotemporal cortex seems a prerequisite for guiding the emerging specialization in the VWFA.

Research by Pedago, Nakamura, Cohen, and Dehaene (2010) supports that the VWFA plays a crucial role in the discrimination of letter orientation, which links to the well-known fact that a deficit in discriminating between a b and a d is a common symptom of dyseidetic dyslexia.

Treatment of dyseidetic dyslexia

Phonological processing and auditory memory are foundational to learning phonics and support the region in the brain that specializes in sounding out words. On the other hand, visual processing skills (such as spatial relations and form discrimination), visual memory, visuospatial memory, and rapid recall are foundational to revisualizing the gestalt of words and support the VWFA.

Rapid recall refers to the speed with which the names of symbols (letters, numbers, colors, or pictured objects) can be retrieved from long-term memory (De Jong & van der Leij, 2003). This process is often termed rapid automatized naming (RAN), and people with dyslexia typically score poorer on RAN assessments than typical readers (Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014).

The good news is that weaknesses in cognitive skills can be attacked head-on; it is possible to strengthen these mental skills through training and practice. Edublox’s Development Tutor aims at strengthening underlying cognitive skills such as visual processing skills, visual memory, visuospatial memory, and rapid recall.

A child with dyseidetic dyslexia will also need training in reading and spelling, which can best be accomplished by Edublox’s live tutoring services. Our live tutoring program is based on the well-known Orton Gillingham approach but simultaneously aims at developing the brain’s visual word form area (VWFA) mentioned above.

The video concerns Hilary and her 9-year-old son, who struggled with dyseidetic dyslexia. Hilary reports measurable improvements in standardized reading scores and confidence.

Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

.

.

Key takeaways

Authored by Susan du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years’ experience in the field of learning disabilities.

.

References and sources:

Brem, S., Maurer, U., Kronbichler, M. et al. (2020). Visual word form processing deficits driven by severity of reading impairments in children with developmental dyslexia. Scientific Reports, 10.

De Jong, P. F., & van der Leij, A. (2003). Developmental changes in the manifestation of a phonological deficit in dyslexic children learning to read a regular orthography. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 22-40.

Elliott, J. G., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2014). The dyslexia debate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Georgetown University Medical Center (2016, June 9). In the brain, one area sees familiar words as pictures, another sounds out words. Retrieved July 15, 2019 from https://bit.ly/2XLzNHd

Pedago, F., Nakamura, K., Cohen, L., & Dehaene, S. (2011). Breaking the symmetry: Mirror discrimination for single letters but not for pictures in the Visual Word Form Area. Neuroimage, 55, 742-749.

Kere, J. (2014). The molecular genetics and neurobiology of developmental dyslexia as model of a complex phenotype. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 452(2), 236-243.

Smith, C. R. (1991). Learning disabilities: The interaction of learner, task, and setting. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Stein, J. (2018). The magnocellular theory of developmental dyslexia. In T. Lachmann, & T. Weis (Eds.). Reading and dyslexia (pp. 97-128). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.