The word repetition and the closely related repeat come from the Latin word repetere, meaning “do or say again” — an action familiar to everyone. There is probably not a single person on Earth who learned to speak a language, swim, skate, play golf, shift gears of a car — or read and write — without repetition.

Rote, the outcome of repetition, means to do something routinely or in a fixed way, to respond automatically by memory alone, without thought (Heward, 2003). Repetition thus leads to fast, effortless, autonomous, and automatic processing (Logan, 1997).

As far as one can go back in history, repetition has been considered the backbone of successful teaching and schooling. Hinshelwood (1917), considered the father of the study of dyslexia, did not doubt that remediation of dyslexia was dependent on frequent repetition. But in the 1920s and 1930s, repetition and rote learning came to define poor teaching. Good teachers don’t fire off quiz questions and catechize kids about facts. They don’t drill students on spelling or arithmetic. Kramer (1997, pp. 65-66) summarizes the advent of progressive education:

The jewel in the crown of American pedagogy has long been Columbia University’s Teachers College. Its patron saint, and of American education more generally, is John Dewey, whose idea of school as engines of social change led his disciples in the 1920s and 1930s to define their task as replacing the rigid, the authoritarian, and the traditional with a school centered on the child’s social, rather than his intellectual, functioning. The child would be freed from the highly structured school day, from testing, rote memorization, and drill. Books were to take second place to projects, reading to “life experience.” Cooperation would replace competition; the emphasis would be on the group rather than the individual. The elementary school pupil would learn about here and now, his neighborhood rather than places in the far-off past. The school was to be a socializing institute where children learned through active experience.

Repetition becomes “mindless”

Dewey’s educational ideas were built on the bases laid by Herbert Spencer (Egan, 2002), an English philosopher who considered rote learning to be a “vicious” system (Cavenagh, 1932, p. 34). While Spencer’s name is rarely mentioned in educational writings today, Dewey’s educational ideas became and are still widely known.

Criticized by some and hailed by others, the fact is that one consequence of Dewey’s influence was that repetition, drilling, and rote learning became “out of style” (Bremmer, 1993), “ghastly boring” (Bassnett, 1999), and even “mindless” (Dixon & Carnine, 1994, p. 360). “Having to spend long periods of time on repetitive tasks is a sign that learning is not taking place — that this is not a productive learning situation,” said Bartoli (1989, p. 294). Teachers were told that drill-and-practice dulls students’ creativity (Heward, 2003) and that rote learning in math classes is anti-right brain and, therefore, potentially criminal, as it robs all learners of the opportunity to develop their human potential (Elliott, 1980). The phrase “drill and kill” is still used in educational circles, meaning that by drilling the student, you will kill their motivation to learn (Heffernan, 2010).

Compare the attitudes and approaches to drill and practice by many academic teachers with the attitudes of educators who are held accountable for the competence of their students. The basketball coach or the music teacher needs no convincing regarding the value of drills and practice on fundamental skills. No one questions the basketball coach’s insistence that his players shoot 100 free throws every day or wonders why the piano teacher has her pupils play scales over and over. It is well understood that these skills are critical to future performance and that systematic practice is required to master them to the desired levels of automaticity and fluency. We would question the competence of the coach or music teacher who did not include drill and practice as a major component of their teaching.

As Heward (2003) points out, drill-and-practice can be conducted in ways that render it pointless, a waste of time, and frustrating for children. When properly conducted, however, drill-and-practice is a consistently effective teaching method. Therefore, it should not be slighted as “low level” and appears just as essential to complex and creative intellectual performance as to a virtuoso violinist’s performance (Brophy, 1986).

Christodoulou (2014) argues that memorizing doesn’t prevent understanding but rather is vital to it. The very processes teachers care about most — critical thinking processes such as reasoning and problem-solving — are intimately intertwined with factual knowledge stored in long-term memory. Knowledge ready in long-term memory is often required as a stepping-stone to understanding something deeper Willingham (2009).

LD students benefit from repetition

Whatever the case may be for the average student, repetition certainly benefits children riddled with learning challenges. Fo example, a meta-analysis of 85 academic intervention studies with learning-disabled (LD) students, carried out by Swanson and Sachse-Lee (2000), found that regardless of the practical or theoretical orientation of the study, the largest effect sizes were obtained by interventions that included systematic drill, repetition, practice, and review.

Automatizing low-level skills frees information-processing capacity for attention to more difficult and higher-level aspects of tasks. One cannot, for example, become a good soccer player if, as you’re dribbling, you still focus on how hard to hit the ball, which surface of your foot to use, and so on. Low-level processes like this must become automatic, leaving room for more high-level concerns, such as game strategy (Brophy, 1986; Willingham, 2009).

The same is true of reading. The child in whom the low-level cognitive skills of reading have not yet become automatic will read haltingly and with great difficulty. A child, for example, whose ability to discriminate between left and right has yet to be automatized, will confuse letters like b and d. Without drill-and-practice of left and right, the child will continue to confuse b and d, with the result that reading ability cannot be automated. Likewise, a child whose reading ability has yet to become automatic will read with poor comprehension, as they must divide their attention between recognizing the words and understanding the message.

From a neuroscientific perspective, repetition is important in the “wiring” of a person’s brain, i.e., the forming of connections or synapses between the brain cells. Without repetition, key synapses don’t form. And if such connections, once formed, are used too seldom to be strengthened and reinforced, the brain, figuring they’re dead weight, eventually “prunes” them away (Hammond, 2015; Bernard, 2010).

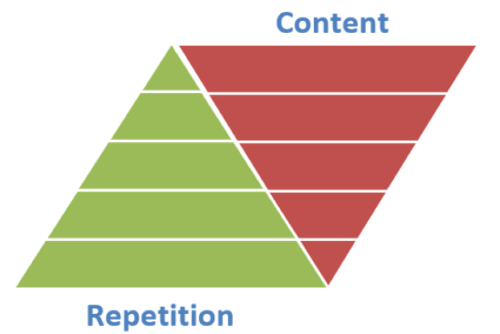

Mere repetition, however, is not the end of the story. A “pyramid of repetition” must be constructed for the beginner learner.

Constructing a “pyramid of repetition”

This principle, derived from the works of Suzuki, means that the beginner learner must start by repeating a limited amount of material many times over and over. But, gradually, less and less repetition will be necessary to master new skills and knowledge.

In his book, Nurtured by Love, Suzuki (1993) shares the story of a little parakeet taught to say in Japanese: “I am Peeko Miyazawa, I am Peeko Miyazawa.” According to Mr. Miyazawa, Peeko’s trainer, it took three thousand repetitions of the word “Peeko” over a period of two months before the bird began to say “Peeko.” After that, “Miyazawa” was added. After hearing “Peeko Miyazawa” only two hundred times, the little bird could say its full name. Then, when Mr. Miyazawa coughed for some days due to a cold, Peeko would say its usual “I am Peeko Miyazawa” and then cough. With less and less repetition, Peeko learned more and more words and also learned to sing. “Once a shoot comes out into the open, it grows faster and faster . . . talent develops talent and . . . the planted seed of ability grows with ever increasing speed” (Suzuki, 1993, p. 6).

No doubt it is the same with a human being, as the following story, also taken from Suzuki (1993, pp. 92-93), illustrates:

Since 1949, our Mrs. Yano has been working with new educational methods for developing ability, and every day she trains the infants of the school to memorize and recite Issa’s well-known haiku. [A haiku is a short Japanese poem, consisting only of three lines.] . . . Children who at first could not memorize one haiku after hearing it ten times were able to do so in the second term after three to four hearings, and in the third term only one hearing.

The importance of this “pyramid of repetition” is also seen in learning a first language. It has been found that a child who is just beginning to talk must hear a word about 500 times before it will become part of his active vocabulary, i.e., before they can say the word (Hornsby, 1984). Two years later, the same child will probably need only one to a few repetitions to learn to say a new word.

In dyslexia intervention, a “pyramid of repetition” can be constructed to develop a particularly weak cognitive skill, and it can be used in the teaching of reading itself, for example, to build what neuroscience has labeled the brain’s “visual word form area,” and even to teach spelling.

Individuality should be kept in mind

In regards to repetition in general and building a “pyramid of repetition” in particular, there are two very important factors that should be kept in mind: The first is that there is great individuality among different people, and even within the same person, in the amount of repetition required to learn something. The amount of repetition that is enough for one person may not necessarily be enough for another. The amount of repetition a certain person requires to master a particular skill may not necessarily be enough to master another skill. Mrs. Butler might need ten lessons to master the skill of driving, Mrs. Brown might need twenty, Mrs. Lane thirty, and Mrs. Jones forty. On the other hand, Mrs. Jones, who struggled to learn to drive, may require only ten lessons to become a sewing expert.

.

Edublox offers live online tutoring to students with dyslexia and other learning disabilities. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

.

References:

Bartoli, J. S. (1989). An ecological response to Coles’s interactivity alternative. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22(5), 292-297.

Bassnett, S. (1999, October 14). Comment. Independent.

Bernard, S. (2010). Neuroplasticity: Learning physically changes the brain. Edutopia. Retrieved February 12, 2020 from https://www.edutopia.org/neuroscience-brain-based-learning-neuroplasticity

Bremmer, J. (1993, April 19). What business needs from the nation’s schools. St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Brophy, J. (1986). Teacher influences on student achievement. American Psychologist, 41, 1069–1077.

Cavenagh, F. A. (Ed.) (1932). Herbert Spenser on education. Cambridge University Press.

Christodoulou, D. (2014). Seven myths about education. London: Routledge.

Egan, K. (2002). Getting it wrong from the beginning: Our progressivist inheritance from Herbert Spencer, John Dewey, and Jean Piaget. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Elliott, P. C. (1980). Going “back to basics” in mathematics won’t prove who’s “right”, but who’s “left” (brain duality and mathematics learning). International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 11(2), 213-219.

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Heffernan, V. (2010, September 16). Drill, baby, drill. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved February 10, 2020 from https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/19/magazine/19fob-medium-heffernan-t.html

Heward, W. L. (2003). Ten faulty notions about teaching and learning that hinder the effectiveness of special education. Journal of Special Education, 36(4), 186-205.

Hinshelwood, J. (1917). Congenital word-blindness. London: Lewis.

Hornsby, B. (1984). Overcoming dyslexia. Johannesburg: Juta and Company Ltd.

Kohn, A. (1998). What to look for in a classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kramer, R. (1997, Winter). Inside the teachers’ culture. The Public Interest, 64-74.

Logan, G. D. (1997). Automaticity and reading: Perspectives from the instance theory of automatization. Reading & Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties, 13(2): 123-146.

Suzuki, S. (1993). Nurtured by love (2nd ed.). USA: Summy-Birchard, Inc.

Swanson, H. L., & Sachse-Lee, C. (2000). A meta-analysis of single-subject design intervention research for students with LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(2), 114-136.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don’t students like school? San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.