Is your child bright but struggling to read? You are not alone—and dyslexia might be the reason.

Most children start school excited to learn. For some, reading comes naturally. However, for children with dyslexia, the journey is different—and often heartbreaking. Letters blur, words ‘flip,’ and what seems easy for others feels impossible.

Dyslexia affects the brain’s ability to process language, but it does not reflect a child’s intelligence or potential. In this article, we will walk you through the most common symptoms of dyslexia, the early warning signs to watch for, and the risk factors that increase the likelihood of a diagnosis. Most importantly, we will share practical ways to help.

With early support, children with dyslexia can thrive—not just survive.

Table of contents:

- What is dyslexia?

- What are the symptoms of dyslexia?

- What are the early warning signs of dyslexia?

- What are the risk factors for dyslexia?

- Overcoming the symptoms of dyslexia

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a neurodevelopmental learning disorder that affects a person’s ability to read, spell, and write—even though they may be intelligent, motivated, and have had access to quality education.

At its core, dyslexia involves difficulty processing language. Children and adults with dyslexia struggle to connect the letters they see on the page with the sounds those letters represent. This affects word recognition, reading fluency, and spelling.

It is important to understand that dyslexia is not caused by laziness, poor teaching, or low intelligence. Many people with dyslexia are bright, creative thinkers. However, their brains process written language differently.

One widely cited definition states (Snowling et al., 2020):

“Dyslexia is a disorder manifested by difficulty in learning to read despite conventional instruction, adequate intelligence, and sociocultural opportunity. It is dependent upon fundamental cognitive disabilities, which are frequently of constitutional origin.”

It often runs in families and can vary in severity.

If dyslexia is not recognized and supported, it can lead to frustration, low self-esteem, and school avoidance. That is why it is so important for parents and teachers to recognize the signs—and act promptly.

What are the symptoms of dyslexia?

Symptoms of dyslexia usually become clear when children start school and begin to focus on learning to read and write. The child’s teacher may be the first to notice a problem.

Symptoms of dyslexia include:

1. Difficulty with phonological processing

Children with dyslexia often struggle with phonological processing—the brain’s ability to recognize and manipulate the sounds of spoken language. This skill is essential for decoding words, spelling, and reading fluency.

The word phonological comes from the Greek word phōnē, meaning “sound.” It refers to how we use the sound structure of language to understand and work with words, both spoken and written.

Symptoms of dyslexia that indicate difficulty in phonological processing include:

- Struggling to decode words—matching letters to their corresponding sounds

- Forgetting the beginning sounds of a word before reaching the end, making blending difficult

- Trouble blending individual sounds into whole words (e.g., sounding out c-a-t but then saying cold)

- Frequent confusion with vowel sounds

- Difficulty identifying and manipulating rhyming sounds, syllables, or beginning and ending sounds.

2. Poor reading fluency

Fluent readers read smoothly, at a natural pace, and with appropriate expression—just like speaking. For children with dyslexia, this kind of effortless reading rarely comes easily.

They may read slowly, hesitantly, or word by word, often without understanding what they have just read. This is more than just a lack of practice—it is a sign that their brains are working overtime to decode each word, leaving little mental energy for comprehension.

Signs of poor reading fluency include:

- Frequent pauses, stumbles, or misreadings

- Reading in a choppy, robotic tone with little expression

- Skipping words or adding extra ones

- Reading the same word correctly in one place and incorrectly in another

Fluency is not just about speed. It is a vital stepping stone to understanding what one reads.

Research spotlight: Fluency and comprehension

A study by Fuchs and colleagues (2001) found that oral reading fluency has the strongest link to comprehension among several common measures:

| Measure | Correlation with Comprehension |

|---|---|

| Oral Recall / Retelling | 0.70 |

| Cloze (Fill-in-the-blank) | 0.72 |

| Question Answering | 0.82 |

| Oral Reading Fluency | 0.91 |

To interpret: A perfect correlation is 1.0. The closer the number is to 1.0, the stronger the relationship. Fluency is not optional—it is foundational.

3. Poor reading comprehension

Children with dyslexia often struggle to understand and remember what they have read. Even when they can decode individual words, the meaning of a sentence—or an entire passage—may escape them.

Because so much mental energy is spent figuring out the words, there is little left for making sense of the content. Moreover, when reading is slow, effortful, and inconsistent, comprehension tends to suffer.

Signs of poor reading comprehension include:

- Difficulty recalling key details from a passage

- Trouble answering questions about what they just read

- Inability to summarize a paragraph or retell a story in the correct order

- Confusion about who did what, when, or why

- Missing the main idea or misinterpreting what the text is really about

In many cases, poor comprehension is made worse by a limited vocabulary. Children with dyslexia often read less than their peers, which means they are exposed to fewer new words—and this, in turn, further slows their understanding.

The result? A child who can read the words aloud but cannot tell you what they mean.

4. Directional confusion

Many children with dyslexia struggle with directionality—the ability to distinguish left from right, track lines of text, and recognize the correct orientation of letters and numbers. This is more than just a phase; it can persist long after other children have mastered these skills.

Directional confusion often leads to letter reversals, mirror writing, and reading mistakes that seem random to others but are rooted in spatial processing difficulties.

Signs of directional confusion include:

- Reversing letters like b and d, or p and q when reading or writing

- Inverting letters such as n and u, or m and w

- Swapping entire words: reading was for saw, on for no, tar for rat

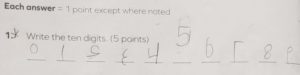

- Reversing numbers: writing 71 instead of 17

- Difficulty reading maps, following directions, or distinguishing left from right

These errors are not due to carelessness—they reflect how a dyslexic brain processes visual and spatial information. Directional confusion can make reading exhausting and unpredictable, especially in the early years.

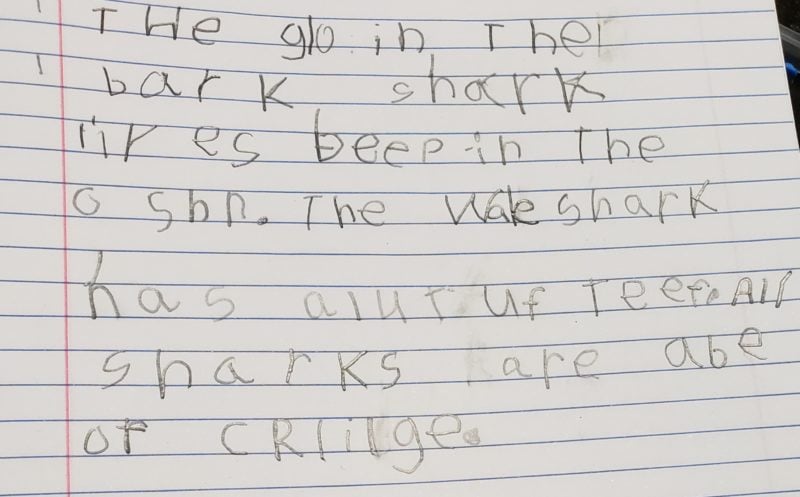

Real-world example:

One 10-year-old boy with dyslexia wrote a thoughtful paragraph about sharks—but his spelling told another story. He consistently reversed letters, turning dark into bark and deep into beep. He also reversed numbers, consistently writing 2, 3, 7, and 9 backward.

Despite his intelligence and effort, these visual confusions made reading and writing far more challenging than they appeared.

5. Sequencing difficulties

Sequencing is the ability to recognize, remember, and reproduce the order of things—whether letters in a word, sounds in speech, or steps in a process. Many children with dyslexia struggle with sequencing, which affects both reading and spelling.

Signs of sequencing difficulties include:

- Reading felt as left, act as cat, or reserve as reverse

- Mixing up syllables: animal becomes aminal, enemy becomes emeny

- Reversing the order of words in a phrase: reading are there as there are

- Misspelling words with letters in the wrong order: Simon becomes Siomn, time becomes tiem

- Leaving out letters: reading or writing cat instead of cart, sing instead of string

These errors can make reading and spelling unpredictable and exhausting—especially when the child appears to “know” the correct answer, but it just will not come out right.

6. Difficulty with small words

Parents often notice something puzzling: their child can read long, complicated words—yet stumbles over simple ones like if, to, and and. It seems careless, but it is not. This inconsistency is a common sign of dyslexia.

Small, high-frequency words often lack strong visual features or phonetic clues. They are harder to sound out and easier to overlook—especially for children with dyslexia.

Signs include:

- Mixing up little words: saying a for and, from for for, or then for there

- Skipping short words or reading them twice

- Adding little words that are not in the text

Researcher John Stein (2014) suggests that this may be due to visual crowding—a perceptual limitation where letters or words become harder to identify when surrounded by other visual stimuli. Small function words, especially in densely packed text, are more likely to be visually “crowded out,” making them harder to recognize.

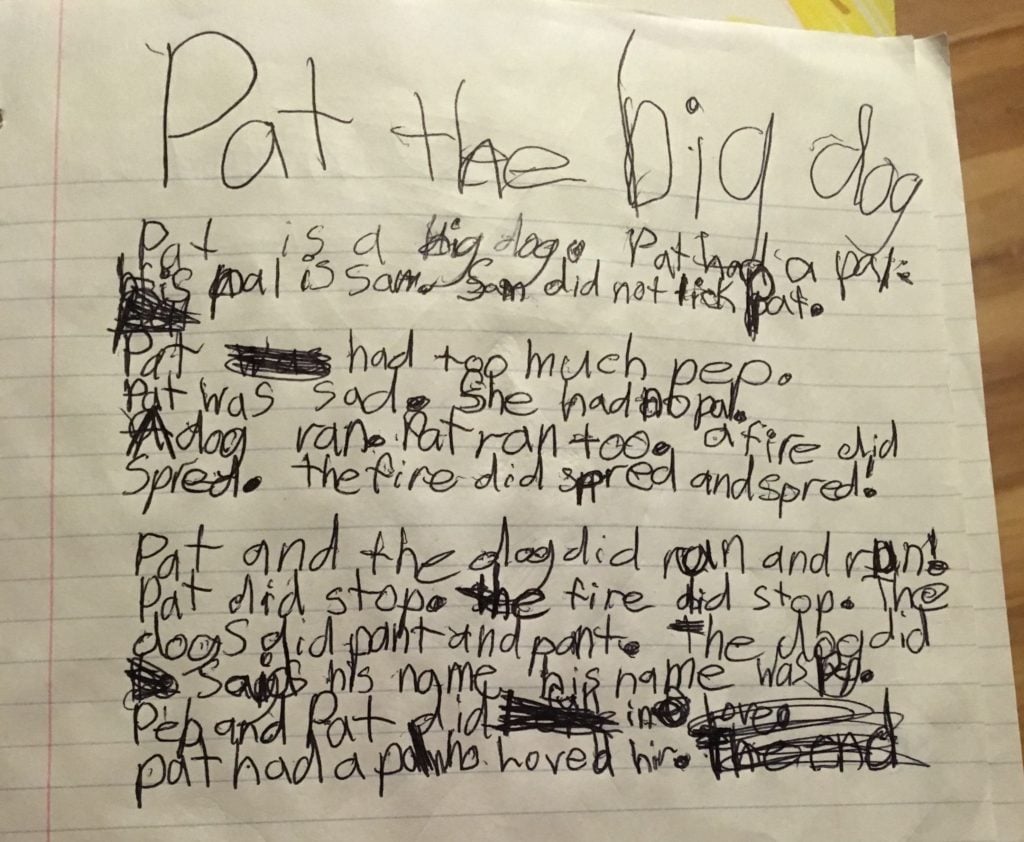

7. Persistent spelling errors

Spelling is often one of the most persistent challenges for children with dyslexia. While all learners make spelling mistakes, the errors made by dyslexic children are typically phonetic, inconsistent, and sometimes resistant to correction.

They may spell the same word in different ways, rely heavily on how the word sounds, or apply rules inappropriately—long after their peers have moved on.

Signs include:

- Phonetic spellings: writing sed for said, or frend for friend.

- Inconsistent attempts: spelling because as becos, bekuz, and bceus on the same page

- Confusing similar-sounding letters: b for d, f for v, ch for sh

- Reversing or jumbling letters: time as tiem.

- Trouble remembering how even familiar words are spelled, despite repeated exposure

- Students with severe dyslexia may spell bizarrely, for example, substance may be spelled ‘sepedns,’ last spelled ‘lenaka,’ about spelled ‘chehat,’ may spelled ‘mook,’ did spelled ‘don,’ or to spelled ‘anianiwe.’ These words bear little—if any—relation to the sounds in the words. (Miles & Miles, 1983).

Spelling difficulties often cause children to avoid words they are unsure how to spell. A child who wants to write arrogant might settle for rude because it is easier to spell. Enormous becomes big, disappear becomes go away.

Over time, this avoidance limits a child’s written vocabulary, sentence variety, and confidence—especially in longer assignments.

8. Guessing at words

Children with dyslexia often guess at unfamiliar words instead of sounding them out. These guesses may be based on the first letter, the overall shape of the word, or even the accompanying pictures—rather than on careful decoding.

While guessing can be a regular part of early reading, it becomes a concern when it persists beyond the early years and replaces systematic reading strategies.

Signs of guessing include:

- Saying window for weather or garden for garage.

- Using a word that fits the sentence contextually but not visually

- Making up a story that loosely fits the pictures but does not match the text

- Skipping difficult words entirely or inserting made-up words

- Relying heavily on memory rather than reading the actual word

Guessing is often a compensatory strategy. When a child has not mastered phonics, decoding, or pattern recognition, guessing seems faster and less frustrating. However, over time, it reinforces poor habits and undermines reading accuracy.

What are the early warning signs of dyslexia?

Dyslexia is usually identified when children begin formal reading instruction, but there are often early clues in a child’s development that something may be off track. These signs can be subtle, and they do not guarantee a future diagnosis—but they are worth paying attention to.

Here are four early warning signs that may indicate a child will struggle with reading and writing later on:

1. Late talking

One of the most common early warning signs of dyslexia is delayed speech development.

Research has demonstrated a strong correlation between early language delays and subsequent reading difficulties. In several longitudinal studies, children with preschool speech or language impairments were more likely to develop reading challenges in their school years (Scarborough, 2005).

A study by Valtin, comparing 100 pairs of dyslexic and typical children, found that those with dyslexia had clear delays in spoken language development. Similarly, Bevé Hornsby, a leading British dyslexia expert, reported that around 60% of children with dyslexia were late talkers.

By the age of five, most children can speak in complete sentences. If a child:

- Spoke late,

- Struggles with pronunciation or articulation,

- Or uses immature grammar when forming sentences at school age,

…these could be early warning signs of dyslexia—or, more broadly, of a language-based learning difficulty.

2. Trouble with nursery rhymes

Young children love rhyme—and for good reason. Nursery rhymes are not just cute and catchy; they help develop an ear for language, which is essential for reading later on.

However, children with dyslexia often struggle to learn or remember rhymes. They may mix up the words, miss the rhyming parts entirely, or choose not to sing along. These difficulties point to weak phonological awareness—a foundational skill for learning to read.

In a well-known study, Bryant and colleagues (1990) found that children who knew more nursery rhymes at the age of three were significantly more successful in reading and spelling by the age of six—even after accounting for differences in IQ, social background, and early phonological skills. The researchers concluded that early exposure to rhymes enhances a child’s sensitivity to the sound structure of language, which in turn supports the development of reading skills.

What to look for:

- Has difficulty learning or reciting simple nursery rhymes

- Does not recognize when words rhyme or sound alike

- Struggles to clap along with rhythm or syllables

- Avoids singing along or appears disinterested in rhyme-based games

These signs do not mean a child will develop dyslexia—but they are often present in children who do.

3. Late walking

While dyslexia is primarily a language-based difficulty, research suggests that motor development may also play a role—especially when delays appear early in life.

One lesser-known early warning sign is late walking. Most children take their first steps between 12 and 15 months and walk confidently by 18 months of age. If a child has not begun walking by 18 months, this could signal broader developmental delays—including those that affect coordination and learning.

Bevé Hornsby reported that approximately 20% of children with dyslexia began walking significantly later than expected. Though not diagnostic on its own, this delay may reflect differences in neurological maturation that also affect reading, sequencing, and balance.

What to look for:

- The child did not begin walking until 18 months or later

- Appears less coordinated than peers during early years

- They took longer to develop motor independence (climbing, running, jumping)

This sign is often subtle, and many late walkers catch up without difficulty. However, in combination with language delays and other early signs, it may help build a clearer picture.

4. Clumsy and accident-prone

Some children who later receive a dyslexia diagnosis appear to be physically awkward in their early years. They may bump into things, drop objects, struggle with tasks that require coordination—like catching a ball or using scissors—and may generally seem more “accident-prone” than their peers.

However, not all children with dyslexia are clumsy. Many are highly capable in sports, and some even excel in movement-based activities.

This makes physical clumsiness a possible warning sign—not a definitive one.

Bevé Hornsby noted that while motor coordination issues are less predictive than language delays, they do occur in a subset of children with dyslexia. Moreover, when they do, activities like trampolining, judo, and swimming can help improve confidence, balance, and overall body awareness.

What to look for:

- Seems uncoordinated compared to peers

- Frequently drops, spills, or bumps into things

- Struggles with catching, jumping, or balancing

- Avoids fine motor tasks like tying shoelaces, cutting with scissors, or using buttons

While clumsiness alone does not indicate dyslexia, when combined with delayed language development or trouble with rhyming, it contributes to the overall developmental picture.

What are the risk factors for dyslexia?

While early warning signs help identify children who may need support, risk factors examine what increases the likelihood of developing dyslexia in the first place. These factors do not cause dyslexia directly, but they are commonly found in children who later struggle with reading.

Here are three of the most researched and relevant risk factors:

1. Heredity

Dyslexia often runs in families. If a parent, sibling, or close relative has experienced reading or spelling difficulties, the chances that a child will struggle are significantly higher.

In the general English-speaking population, dyslexia affects an estimated 5 to 17% of individuals. However, in children with a close family member who has dyslexia, studies show that the rate rises to 35 to 40%.

This is not just about reading habits—it reflects shared patterns in how the brain processes written language. Skills such as phoneme awareness, word recognition, and spelling memory often exhibit similar weaknesses across generations.

If there ia a history of late reading, spelling struggles, or even undiagnosed school difficulties in the family, it is worth monitoring a child’s early reading development more closely.

2. Recurring ear infections

Frequent ear infections in early childhood—especially during the first three years—may interfere with language development. These infections, often referred to as glue ear or otitis media, can reduce hearing for weeks or even months at a time. When this happens repeatedly, it can deprive the developing brain of the clear sound input it needs to build early language skills.

Language development is the foundation for reading. If a child cannot hear speech sounds clearly during the critical years for phonological learning, they may struggle later with sound discrimination, phoneme blending, and word decoding.

In an eight-year study, Peer (2002) assessed 1,000 children and adults referred for reading difficulties. Of these, 703 had experienced severe glue ear, while only 297 had not—suggesting a strong correlation between recurring ear infections and literacy challenges.

Although ear infections are common in young children and do not always lead to reading problems, persistent or untreated cases may be a contributing risk factor for dyslexia.

3. Left-handedness and mixed handedness

While most people are right-handed, children with dyslexia are more likely to be left-handed, ambidextrous, or show mixed hand dominance—for example, writing with one hand but eating or throwing with the other.

This difference in handedness may reflect less typical brain lateralization—meaning that certain language functions are not as strongly located in the brain’s left hemisphere, which is usually dominant for speech and reading in right-handed individuals.

A meta-analysis by Eglinton and Annett (1994) found a statistically significant increase in non-right-handedness among individuals with dyslexia compared to those without the condition. Although being left-handed does not cause dyslexia, it may be one of several factors associated with atypical brain development.

Left-handedness alone is not a red flag. However, when combined with other signs—such as speech delays or difficulty with rhyming—it may support the case for further investigation.

Overcoming the symptoms of dyslexia

Dyslexia presents real and lasting challenges, but with the proper support, children can learn to read, write, and achieve academic success.

Effective intervention addresses both the cognitive foundations of reading and the academic skills themselves.

1. Strengthen the foundations

Reading depends on more than phonics. Children also need strong cognitive skills, such as phonological awareness, processing speed, sequencing, and visual and auditory memory. These skills support accurate decoding and fluent reading.

If these underlying abilities are weak, learning to read becomes a challenging task—regardless of the method used.

Targeting the foundations of learning—rather than only the symptoms—can make a meaningful difference.

2. Use structured, explicit teaching

Children with dyslexia benefit from structured instruction that is clear, sequential, and systematic. This includes:

- Teaching phonics and spelling rules step-by-step

- Practicing decoding and fluency regularly

- Building vocabulary and reading comprehension over time

Instruction should be direct, carefully scaffolded, and adjusted to the student’s pace.

3. Support the whole child

Because dyslexia affects confidence as much as performance, emotional support matters. Encouragement, consistency, and small daily successes help children regain a sense of control and motivation.

With steady input, the right tools, and sufficient time, most children with dyslexia can close the gap—and continue to make progress.

At Edublox, we support children with dyslexia by strengthening their cognitive skills and providing structured, research-based reading and spelling help. Our programs are used worldwide and have helped thousands of students make measurable progress.

Discover more about our approach to dyslexia by scheduling a free consultation with a specialist.

References for Dyslexia Symptoms, Early Warning Signs, and Risk Factors:

- Bryant, P. E., MacLean, M., Bradley, L., & Crossland, J. (1990). Rhyme and alliteration, phoneme detection, and learning to read. Developmental Psychology, 26(3), 429–438.

- Eglinton, E., & Annett, M. (1994). Handedness and dyslexia: A meta-analysis. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 79(3), 1611–1616.

- Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), 239–256.

- Hornsby, B. (1996). Overcoming dyslexia: A straightforward guide for families and teachers. London: Vermilion.

- Miles, T. R., & Miles, E. (1983). Help for dyslexic children. London: Sheldon Press.

- Peer, L. (2002). Dyslexia, multilingual speakers and otitis media (Doctoral dissertation, University of Sheffield, UK). Department of Psychology, University of Sheffield.

- Scarborough, H. S. (2005). Developmental relationships between language and reading: Reconciling a beautiful hypothesis with some ugly facts. In H. W. Catts & A. G. Kamhi (Eds.), The connections between language and reading disabilities (pp. 3–24). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Snowling, M. J., Hulme, C., & Nation, K. (2020). Defining and understanding dyslexia: Past, present and future. Oxford Review of Education, 46(4), 501–513.

- Stein, J. (2014). Dyslexia: The role of vision and visual attention. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 1(4), 267–280.

- Valtin, R. (1989). Dyslexia in the German language. In P. G. Aaron & R. M. Joshi (Eds.), Reading and writing disorders in different orthographic systems (pp. 93–104). NATO ASI Series, Vol. 52. Dordrecht: Springer.

Dyslexia Symptoms, Early Warning Signs, and Risk Factors was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyslexia specialist with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities and medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).

Edublox is proud to be a member of the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), a leading organization dedicated to evidence-based research and advocacy for individuals with dyslexia and related learning difficulties.