The history of dyslexia stretches back nearly a century and a half. It begins in 1877, when German neurologist Adolph Kussmaul described certain patients who, despite intact vision and intelligence, could not learn to read. He coined the term word blindness and urged medical science to study reading problems as a distinct disorder. His observations sparked a conversation that would span neurology, ophthalmology, psychology, education, and ultimately, neuroscience. Over the decades, the concept of dyslexia has been redefined, renamed, and reframed — yet always with the same central puzzle: why can intelligent children struggle so profoundly with reading?

Table of contents:

- Berlin, Kerr, and Morgan

- Early pioneers

- Dyslexia in the 1960s

- Samuel A. Kirk and the LD movement

- Education for All Handicapped Children Act

- The linguistic turn

- The neuroscience era

- Global policy and recognition

- Advocacy, myths, and public perception

- Terminology through time

- Dyslexia today

Berlin, Kerr, and Morgan

In 1884, German ophthalmologist Rudolf Berlin introduced the term dyslexia. He derived it from the Greek dys (ill or bad) and lexis (word), placing it alongside other neurological terms of the era, such as alexia and paralexia (Kirby, 2020). Berlin described six patients who, after brain injury, lost the ability to read while retaining fluent speech. We now call this acquired dyslexia.

The idea of developmental dyslexia, however, emerged a decade later. British physician James Kerr and ophthalmologist Pringle Morgan noticed that otherwise intelligent children could not learn to read. Morgan’s famous 1896 Lancet article described 14-year-old Percy, who was bright and articulate but unable to read or write. Morgan recorded:

The schoolmaster who has taught him for some years says that he would be the smartest lad in the school if the instruction were entirely oral.

This case illustrated what is now recognized as developmental dyslexia — a difficulty learning to read, independent of intelligence or vision.

Early pioneers

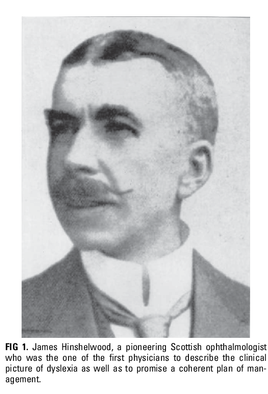

The British ophthalmologist James Hinshelwood expanded Berlin and Morgan’s work. He distinguished between acquired and congenital word blindness, arguing that congenital cases were hereditary yet remediable, and more common in boys. He believed the root cause lay in the left angular gyrus, which failed to store visual memories of words.

Across the Atlantic, American neurologist Samuel T. Orton challenged the idea of blindness altogether, coining strephosymbolia (“twisted symbols”). Orton believed that reading difficulties stemmed from faulty perceptual processing and incomplete cerebral dominance, leading to left–right confusion and letter reversals.

In 1925, Orton established a mobile clinic in Iowa and evaluated struggling readers. Whereas Hinshelwood had bristled at the idea that one per thousand students in elementary schools might have “word blindness,” Orton offered that “somewhat over 10 percent of the total school population” had reading disabilities (Orton 1925 & 1939, as cited in Hallahan et al., 2002).

Working with Anna Gillingham, Orton developed structured, multisensory teaching methods that remain the basis of Orton–Gillingham approaches today. Around the same time in California, educator Grace Fernald pioneered her “kinesthetic method” at UCLA, encouraging children to trace, say, and write words until recognition became automatic. Her multisensory emphasis paralleled Orton–Gillingham and influenced later structured literacy practices.

Orton’s work inspired many, and decades later, it influenced neurologist Norman Geschwind, whose research in the 1960s and 1970s on cerebral dominance and disconnection within left-hemisphere language networks revived neuroanatomical interest in reading disorders. Geschwind’s models helped link developmental dyslexia with the patterns seen in acquired aphasias.

Although Orton passed in 1948, his legacy lived on. In 1949, a group of physicians, educators, and parents established the Orton Society in New York to honor his work. It was later renamed the Orton Dyslexia Society and is known today as the International Dyslexia Association (IDA).

As a result of Orton’s research, dyslexia passed from medical to educational ownership and began to be ‘treated’ through educational development rather than medical intervention (Macdonald, 2010).

Dyslexia in the 1960s

At the beginning of the 20th century, only a small number of children were diagnosed with congenital word-blindness or dyslexia. Because their features were distinct from the recognized handicap categories, they were often excluded from formal special education services. This situation changed gradually, culminating in the 1960s, as research on brain injury and learning difficulties converged.

Following World War I, German neurologist Kurt Goldstein studied large numbers of brain-injured soldiers. He provided systematic descriptions of conditions such as aphasia, agnosia, and tonus disturbances, and showed how brain damage could alter perception, behavior, and mood. Goldstein also devised rehabilitation programs, demonstrating that recovery and retraining were possible.

Inspired by Goldstein’s work, Jewish émigré scholars Alfred A. Strauss and Heinz Werner began studying adolescents in U.S. institutions during the 1930s. They observed that some intellectually disabled adolescents displayed perceptual and learning disorders similar to those seen in Goldstein’s soldiers. They distinguished between an endogenous type (with familial intellectual disability) and an exogenous type (linked to brain injury) (Franklin, 1987). Although later reanalysis showed their distinction was weak (Kavale & Forness, 1985), Strauss and Werner’s work laid the cornerstone of what would become the field of learning disabilities.

By the 1940s and 1950s, Strauss and colleagues extended their research to children of normal intelligence who showed perceptual and learning difficulties. They concluded — controversially — that these children, too, had suffered “minor brain injury.” This reasoning produced the label minimal brain dysfunction (MBD), an umbrella term that included dyslexia alongside over a hundred unrelated childhood problems, from strabismus to abnormal sleep (Clements, 1966). Although overly broad and ultimately rendered obsolete, MBD marked a crucial transitional stage: dyslexia was framed as part of a spectrum of brain-based disorders rather than as a purely educational anomaly.

The 1960s witnessed an explosion of perceptual-motor training programs, led by figures such as Lehtinen, Frostig, Ayres, Getman, Kephart, and Barsch. These programs promised to remediate children’s dysfunctions through exercises targeting visual-motor coordination, balance, and spatial awareness. Schools adopted them widely, reflecting the era’s optimism about remediation through training.

However, later systematic reviews of more than 80 studies and 500 statistical comparisons concluded that these methods produced little or no improvement in reading or academic achievement (Kaufman, 2008). The failure of perceptual-motor training ultimately pushed the field to look elsewhere — particularly toward the role of language and phonological processing, which became the dominant focus in the decades that followed.

Samuel A. Kirk and the LD movement

In 1963, American psychologist Samuel A. Kirk coined the term learning disabilities (LD) to describe children with difficulties in language, speech, reading, and communication that could not be explained by low intelligence or sensory deficits. Parents eagerly embraced the label, forming advocacy groups such as the Association for Children with Learning Disabilities.

Kirk’s terminology framed dyslexia within a broader LD movement, leading to political and educational recognition.

Education for All Handicapped Children Act

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) of 1975 introduced a watershed change, guaranteeing special education services in U.S. public schools. Dyslexia now had legal standing as a learning disability. The law required schools to identify affected students, though the IQ-achievement discrepancy model often meant waiting until third or fourth grade — the so-called “wait-to-fail” model (Hallahan, Kauffman, & Pullen, 2015).

This approach later gave way to Response to Intervention (RTI), a tiered model of escalating support that aims to identify struggling readers earlier.

The linguistic turn

By the 1970s and 1980s, researchers such as Frank Vellutino (1979) and Keith Stanovich (1988) redirected the field from perceptual theories toward phonological processing. They demonstrated that children with dyslexia struggle primarily with breaking words into sounds (phonemic awareness) and mapping those sounds to letters.

The phonological deficit hypothesis became the dominant explanatory model and underpinned the design of phonics-based interventions.

In the 1990s, Maryanne Wolf and colleagues proposed the double-deficit hypothesis, noting that some dyslexic readers also had deficits in rapid automatized naming (RAN). This dual framework explained why some children with dyslexia struggle more severely than others (Wolf & Bowers, 1999).

The neuroscience era

From the 1990s onward, neuroimaging revolutionized dyslexia research. PET and fMRI studies showed that readers with dyslexia consistently underactivate the left hemisphere reading network — particularly the temporo-parietal and occipito-temporal regions. Compensatory overactivation was sometimes observed in right-hemisphere areas.

These discoveries cemented dyslexia as a neurobiological condition, not a matter of laziness or poor teaching. They also aligned with the concept of neuroplasticity: intensive reading intervention can rewire these circuits, normalizing brain activation patterns.

IQ is not related to dyslexia

For much of the 20th century, dyslexia was identified through the IQ-achievement discrepancy model: children were considered dyslexic if their reading achievement was far below what their IQ predicted. This definition excluded many struggling readers with an average or below-average IQ, leaving them without support.

Research beginning in the 1990s dismantled this view. Longitudinal and neuroimaging studies have shown that children with poor reading skills exhibit similar phonological and neural deficits, regardless of their IQ level. Functional brain scans demonstrated identical patterns of underactivation in the left hemisphere reading network among poor readers with both high and low IQ scores.

In other words, dyslexia is independent of intelligence. A child can be gifted and dyslexic, or have average or even below-average IQ and still show the same hallmark difficulties in phonological processing and word recognition.

As Vellutino and colleagues (2000) concluded:

The processes responsible for reading difficulties in poor readers are the same, irrespective of IQ.

This finding has reshaped identification practices. The IQ-achievement model has been largely abandoned, replaced by approaches that emphasize early screening, phonological assessment, and responsiveness to intervention.

Global policy and recognition

In the United Kingdom, the Warnock Report (1978) formally acknowledged dyslexia within special educational needs. This recognition spread internationally, with governments adopting accommodations such as extended exam time and alternative formats.

In the United States, the EAHCA evolved into the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which reinforces protections and ensures that children with dyslexia receive specialized instruction tailored to their needs.

Advocacy, myths, and public perception

Alongside scientific progress came advocacy — and mythology. Media and advocacy groups often claimed that historical geniuses such as Einstein, Leonardo da Vinci, Walt Disney, or Hans Christian Andersen were dyslexic. These stories popularized dyslexia, but were often inaccurate; careful biographical study reveals little evidence to support many of these claims.

Nonetheless, the myth of dyslexia as the “affliction of geniuses” fueled public awareness and advocacy movements that secured legal recognition and educational reforms (Stanovich, 1989).

Terminology through time

Over the decades, dyslexia has gone by many names: word blindness, word amblyopia, thypholexia, amnesia visualis verbalis, analfabetia partialis, bradylexia, script-blindness, psychic blindness, primary reading retardation, developmental reading backwardness, and Orton’s strephosymbolia. Most of these have been discarded.

Today, the preferred terms are dyslexia, reading disability, and learning disability. Modern diagnostic systems classify it as:

- DSM-5 (2013): Specific learning disorder with impairment in reading

- ICD-11 (2019): Developmental learning disorder

Dyslexia today

In the 21st century, dyslexia is no longer seen as the result of a single cause. While the phonological deficit hypothesis remains the dominant explanation, more recent work highlights the complexity of multiple interacting risk factors.

The multiple deficit model

Psychologist Bruce Pennington (2006) advanced the multiple deficit model, arguing that developmental disorders like dyslexia emerge not from one deficit but from the interplay of genetic, cognitive, and environmental influences. This model explains why children with dyslexia display different profiles of difficulty and why dyslexia often co-occurs with ADHD, speech or language disorders, and other learning problems. It replaced the “one-size-fits-all” framework with a more nuanced understanding of reading disability as a spectrum condition.

Classification in diagnostic manuals

The inclusion of dyslexia in modern diagnostic systems (DSM-5 and ICD-11) has had a profound impact. By embedding dyslexia in authoritative medical manuals, the condition is recognized worldwide as a genuine neurodevelopmental disorder rather than a vague educational problem.

This recognition has shaped policy, funding, and legal rights. In schools and universities, students with dyslexia now qualify for accommodations such as extended exam time, assistive technology, or alternative test formats. Governments and institutions use DSM and ICD classifications as a framework for allocating resources, training teachers, and ensuring that children with dyslexia receive systematic support.

The Science of Reading

The last decade has seen the rise of the Science of Reading (SoR) movement, which seeks to align classroom practice with decades of cognitive and linguistic research. SoR emphasizes systematic phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension, countering earlier “whole language” and “balanced literacy” approaches that often left struggling readers behind. This movement has influenced policy debates, teacher training, and curriculum reform across several countries.

Current consensus

Today, dyslexia is recognized as:

- A neurobiological condition independent of IQ.

- The result of multiple interacting deficits, not a single cause.

- A specific learning disorder, classified in DSM-5 and ICD-11.

- Best addressed through structured, evidence-based literacy instruction informed by the Science of Reading.

From Kussmaul’s word blindness in 1877 to the multiple deficit models of today, the history of dyslexia reflects an evolving scientific and educational effort to understand why reading is so difficult for some children — and, more importantly, how to help them succeed.

.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia. We support families in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

References for A Comprehensive History of Dyslexia:

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

- Clements, S. D. (1966). Minimal brain dysfunction in children; terminology and identification. Phase one of a three-phase project. U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED022289.pdf

- Franklin, B. M. (1987). From brain injury to learning disability: Alfred Strauss, Heinz Werner and the historical development of the learning disabilities field. In B. M. Franklin (Ed.), Learning disability: Dissenting essays (pp. 29–46). Philadelphia, PA: Falmer Press.

- Hallahan, D. P., Bradley, R., & Danielson, L. (Eds.). (2002). Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice. Routledge.

- Hallahan, D. P., Kauffman, J. M., & Pullen, P. C. (2015). Exceptional learners: Introduction to special education (13th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Kaufman, A. S. (2008). Neuropsychology and specific learning disabilities: Lessons from the past as a guide to present controversies and future clinical practice. In E. Fletcher-Janzen & C. R. Reynolds (Eds.), Neuropsychological perspectives on learning disabilities in the era of RTI: Recommendations for diagnosis and intervention (pp. 1–13). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kavale, K. A., & Forness, S. R. (1985). The science of learning disabilities. San Diego: College Hill Press.

- Kirby, P. (2020). Dyslexia debated, then and now: A historical perspective on the dyslexia debate. Oxford Review of Education, 46(4), 472-486.

- Macdonald, S. J. (2010). Towards a sociology of dyslexia: Exploring links between dyslexia, disability and social class. VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

- Morgan, W. P. (1896). A case of congenital word blindness. British Medical Journal, 2(1871), 1378.

- Stanovich, K. E. (1988). Explaining the differences between the dyslexic and the garden-variety poor reader: The phonological-core variable-difference model. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 21(10), 590–604.

- Stanovich, K. E. (1989). Learning disabilities in broader context. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22(5), 287-291, 297.

- Vellutino, F. R. (1979). Dyslexia: Theory and research. MIT Press.

- Vellutino, F. R., Scanlon, D. M., & Lyon, G. R. (2000). Differentiating between difficult-to-remediate and readily remediated poor readers: More evidence against the IQ–achievement discrepancy definition of reading disability. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33(3), 223–238.

- Wolf, M., & Bowers, P. G. (1999). The double-deficit hypothesis for the developmental dyslexias. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 415–438.

- World Health Organization. (2019). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision).

A Comprehensive History of Dyslexia was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyslexia specialist with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities.

Edublox is proud to be a member of the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), a leading organization dedicated to evidence-based research and advocacy for individuals with dyslexia and related learning difficulties.