Table of contents:

- The importance of reading

- What is the Matthew Effect in reading?

- Studies on the Matthew Effect report mixed results

- The Matthew Effect and closing the gap

- Closing the gap: A parent’s testimony

The importance of reading

Reading is essential to success in our society. A study by Gallup on behalf of the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy found that low levels of adult literacy could be costing the U.S. as much as $2.2 trillion a year (Nietzel, 2020).

Adults with inferior reading skills compose a large number of high school dropouts, unemployed, living in poverty or receiving government assistance, and incarcerated.

Reading is a skill that serves society and the individual throughout his life, yet it is a skill that many people take for granted. For most children, reading is acquired effortlessly as they progress through the early school years, and it serves as the primary mechanism used to acquire knowledge throughout their education.

Children’s literacy skills grow rapidly during the elementary school years. They begin with understanding the alphabetic principle of letter-sound correspondences and progress to understanding prefixes and suffixes as they decode unfamiliar words. Children continue to refine their comprehension skills as they move from answering simple questions related to picture texts to identifying cause and effect in narrative and expository literature. As children reach the end of elementary school, they can participate in oral presentations, read nonfiction texts, and “publish” their original writing.

Reading in the adolescent years brings new demands for the reader. While adolescents have usually mastered the fundamentals of word analysis and recognition, they continue to learn about the Latin and Greek origins of words and expand their vocabularies as they become more sophisticated readers. Adolescents bring their acquired knowledge and experience to learn from the text they read and acquire new ways to learn from text. Students must be able to problem-solve, read from two different perspectives, and reflect on and analyze reading material. Adults continue to rely on their reading skills to keep pace with advances in their profession, stay informed of current news, and engage in reading for pleasure (Giess, 2005).

What is the Matthew Effect in reading?

Typically, students with reading difficulty have struggled academically throughout school, often just barely passing each grade level. Some students never received good reading instruction and experienced poor environmental conditions in childhood. Some have a specific learning disability in reading, often called dyslexia.

Dyslexia has been recognized as a learning disability for many decades. Some dyslexia experts maintain that the term “dyslexia” should be reserved only for people who experience difficulty with reading. Other experts argue that dyslexia describes a broad set of neurological differences that impact various capacities, including listening, speaking, reading, writing, sequencing, and remembering. All dyslexia experts agree that dyslexia accounts for why some children have more difficulty learning to read than their peers. Even a slight reading delay can translate into a significant gap between what a child is expected to read at school and what they can learn from reading in a few short years.

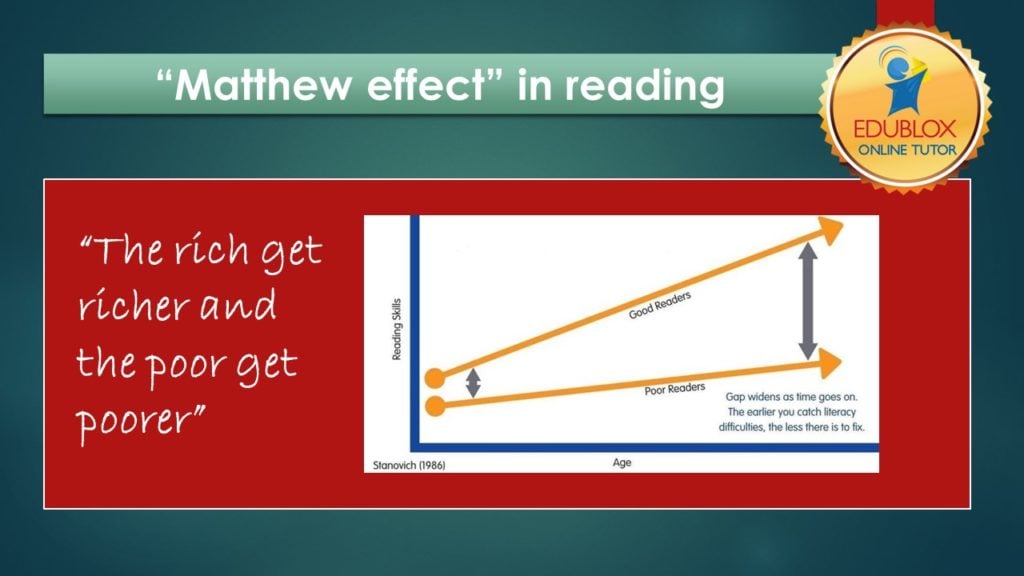

This gap is often exacerbated for children with dyslexia because they tend to avoid reading. It is an understandable avoidance; for these children, reading is arduous. However, avoidance puts them at an even greater disadvantage. This phenomenon is referred to as the Matthew Effect, a term coined by Robert K. Meron in 1968 and adopted for education by psychologist Keith Stanovich in 1986.

In the biblical story of Matthew, the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer. In the case of young readers, good readers read more and get better at reading, whereas less-skilled readers read less and fall farther and farther behind their peers. In time, the difference in reading ability can become significant and begin to impact other areas of learning, such as vocabulary development and comprehension.

Other capacities, such as speaking and writing, can also be influenced by how much reading a child does. For many children with dyslexia, delayed progress in these areas diminishes their self-esteem and motivation to complete schoolwork, which can further hinder their ability to learn at school (Franklin, 2018). In the words of Stanovich (1986):

Slow reading acquisition has cognitive, behavioral, and motivational consequences that slow the development of other cognitive skills and inhibit performance on many academic tasks. In short, as reading develops, other cognitive processes track the reading skill level. Knowledge bases in reciprocal relationships with reading are also inhibited from further development. The longer this developmental sequence is allowed to continue, the more generalized the deficits will become, seeping into more and more areas of cognition and behavior. Or, to put it more simply – and sadly – in the words of a tearful nine-year-old, already falling frustratingly behind his peers in reading progress, “Reading affects everything you do.”

Studies on the Matthew Effect report mixed results

Studies attempting to confirm the Matthew Effect in reading report mixed results. Protopapas and team (2015) followed 587 Greek students of varying reading, spelling, and vocabulary skills for two years, from Grades 2 through 4. The authors conclude that the Matthew Effect pattern was not evident. However, there was no evidence of eventually closing the gap either. Thus, “although the poor students may not be getting poorer, they do not get sufficiently richer either.”

Cunningham and Stanovich (1997) followed up on 11th graders who were administered a battery of reading tasks in 1st grade. Ten years later, they were administered measures of exposure to print, reading comprehension, vocabulary, and general knowledge. First-grade reading ability was a strong predictor of all of the 11th-grade outcomes and remained so even when measures of cognitive ability were partialled out.

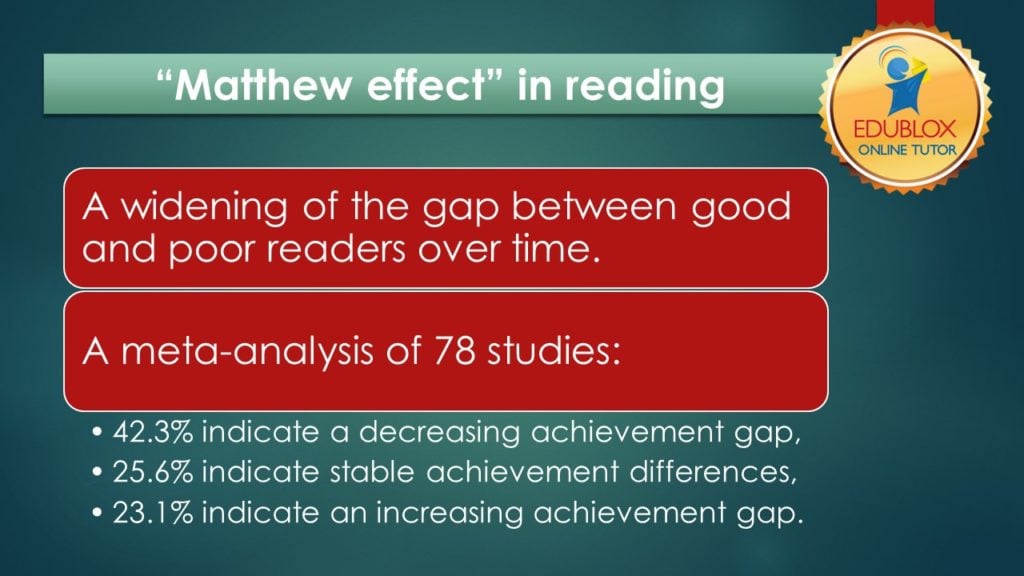

A meta-analysis of 78 studies reports that 33 studies (42.3%) indicated a decreasing achievement gap, 20 (25.6%) indicated stable achievement differences, and 18 (23.1%) indicated an increasing achievement gap or Matthew Effect. Furthermore, 6 (7.7%) results indicated a pattern of delayed compensation, which means that these studies first found increasing and subsequently found decreasing achievement differences (Pfost et al., 2014).

The Matthew Effect has led to several legal issues over the years, such as the 1997 court case of James Brody versus the Dare County Public Schools. James Brody was found eligible for special education after being administered an IQ test in the 3rd grade. After three years of special education, he was retested. According to the new testing, his IQ had dropped from 127 to 109.

Two years later, when James was retested again, his IQ had dropped even further. Experts testified that James’s declining IQ test scores were an example of the Matthew Effect and evidence that James was not receiving appropriate remediation. The Administrative Law Judge and the Review Officer agreed and found that the school district had not provided James with an appropriate education (Briggs, 2013).

.

The Matthew Effect, and closing the gap

Closing the gap: A parent’s testimony

My son Preneil was diagnosed with dyslexia in June 2010. He was in Grade 7! We were both quite unsettled and not sure of the way forward. Not only did he have to attend a school program to help learners struggling with reading but he also had to work with me every night completing exercises in eye movement and word recognition. The issue that troubled Preneil the most was that he was labeled by fellow students as a “remedial” child. Preneil’s confidence was always quite fragile given his small stature and quiet, introspective nature but this diagnosis dragged him back even further.

Both his teachers and I picked up quite early in his schooling career that Preneil struggled with reading. I had his eyes and hearing tested but found that both were fine. He participated in several reading programs but there was no significant improvement in his reading. His teachers never recommended that he be tested for ADD or any reading disability, so it never occurred to me that Preneil could be dyslexic.

To find out when he was 13 (Grade 7) filled me from feelings of anger and annoyance to sadness and despair. I had not been able to give Preneil the support he needed and I could only imagine the frustration he experienced from one class to the next. The program he attended in school didn’t show any improvement in his reading.

He entered high school and the first 6 months were difficult to say the least. Preneil was withdrawn and tried very hard to “look” happy because he didn’t want to worry me. At the end of the 2nd term he had failed Afrikaans [additional language] and obtained 42% for English. Our morale was at an all time low. I did not know how to help my child.

As is common with 21st century moms I spent many hours on Google researching possible solutions. I came across Edublox and found out that there was a center in our area. But it was only after a glowing reference from a previous participant of Edublox that I registered Preneil into the program. The facilitator at Edublox, Sue, confidently told me to give her 18 months to turn Preneil around.

Preneil has been in the program for 22 months, attending one lesson per week. His English has jumped from 42% to 58%; he is writing compositions that bring tears to my eyes. His imagination and vocabulary is astounding even though his spelling needs a little more work.

Preneil was reassessed for dyslexia in April 2013. The report indicated that only a few symptoms of dyslexia could be picked up. Preneil has managed to overcome this difficulty which we can only ascribe to his participation in the Edublox program.

Devigi Pillay

June 25, 2013

.

.

Update, January 6, 2016:

From: Pillay, Devigi [mailto:Pillay.D@]

Sent: January 06, 2016 12:34 PM

To:[email protected]

Subject: Edublox

Dear Sue

I trust you are well and still hold fond memories of Preneil and I.

I wanted to drop you a short note to thank you for the time, effort, knowledge and skills that you invested in Preneil during his time at your center. I firmly believe that it was this foundation that helped him pass Matric [12th grade] comfortably with an A in Math Literacy. More importantly, Preneil achieved 63% in English! For Pren and I this is the greatest achievement! We will always be most appreciative of your support and encouragement.

Preneil will be following a career in Human Resources at TUT this year.

Thank you and Take care.

Regards,

Devi

.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and other learning disabilities. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Matthew Effect in reading – key takeaways

Authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities.

.

References and sources:

Briggs, S. (2013). The matthew effect: what is it and how can you avoid it in your classroom? InformEd

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 934–945. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.934

Franklin, D. (2018). Helping your child with language-based learning disabilities. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Giess, S. (2005). Effectiveness of a multisensory, Orton-Gillingham influenced approach to reading intervention for high school students with reading disability (Unpublished dissertation). University of Florida.

Nietzel, M. T. (2020, September 9). Low literacy levels among U.S. adults could be costing the economy $2.2 trillion a year. Forbes.com

Pfost, M., Hattie, J., Dörfler, T., & Artelt, C. (2014). Individual differences in reading development: A review of 25 years of empirical research on Matthew effects in reading. Review of Educational Research, 84(2), 203–244. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313509492

Protopapas, A., Sideridis, G. D., Mouzaki, A., & Simos, P. G. (2011). Matthew effects in reading comprehension: Myth or reality? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 44(5), 402–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219411417568

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360-407.