We discuss 45 signs of dyslexia in children: the typical errors dyslexic kids make in reading and writing, and how dyslexia looks like in the classroom.

We specialize in helping children overcome dyslexia signs and symptoms. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Table of contents:

- A mom tells her story

- What is dyslexia?

- Signs of dyslexia in reading

- Signs of dyslexia in writing

- Signs of dyslexia in the classroom

A mom tells her story

One day after school, Jonathan’s mom told him to remove his lunchbox from his schoolbag, put his shoes away, and drop his clothes in the washing basket. About 10 minutes later, she popped into his room, only to see him sitting on his bed – still in his school uniform.

“Jonathan was always in trouble with me because I thought he wasn’t listening,” says his mom, Ann. “I thought he was lazy.”

To make matters worse, seven-year-old Jonathan often got poor behavior reports at school and was mocked by his friends because he couldn’t read or spell.

At the end of 2nd grade, Ann and her husband, John, were told their son might have to repeat the year. He was swapping the letters “b” and “d,” he couldn’t spell, his concentration was poor, and he struggled to distinguish left from right.

“Jonathan didn’t want to go to school,” Ann says. “He said he wished he was dead so he wouldn’t have to battle anymore.”

It turns out Jonathan wasn’t a lazy boy. He has dyslexia.

What is dyslexia?

The term dyslexia was coined from the Greek words dys, meaning ill or difficult, and lexis, meaning word. Developmental dyslexia distinguishes the problem in children and youth from similar issues experienced by persons after severe head injuries.

Dyslexia is not easy to define, mainly because the term encompasses a wide and differing range of characteristics. Traditionally, dyslexia was defined as a discrepancy between actual reading performance and what would be expected based on the child’s intelligence. The ‘true dyslexic’ was typically someone who, despite struggling with reading, is above average in intelligence. When children were less intelligent, psychologists ascribed their reading troubles to their general intellectual limitations.

Using brain imaging scans, however, Tanaka et al. (2011) found no differences in how poor readers with or without dyslexia think while reading. Poor readers of all IQ levels showed significantly less brain activity in six observed areas. These findings were largely replicated by Simos et al. (2014).

The British Dyslexic Association describes dyslexia in very general terms as “…a combination of abilities and difficulties defined by its characteristics that affect the learning process in one or more areas of reading, spelling, and writing.”

The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association) uses the term ‘Specific Learning Disorder with impairment in reading’ to describe what others call dyslexia. It considers dyslexia “specific” for four reasons: it is not attributable to

- an intellectual disability, generally estimated by an IQ score of 65-75;

- a global developmental delay;

- hearing or vision disorders; or

- neurological or motor disorders.

Signs of dyslexia in reading

When you look closely at how children with dyslexia read, you see that there are specific patterns, says Wood (2005). Dyslexic children make particular kinds of reading errors. They may:

- Read a word on one page but not recognize the same word on the next page.

- Read single words slowly and inaccurately without a storyline or other clues.

- Misread words with the same first and last letters or shapes, reading form instead of from, or trial instead of trail.

- Add or leave out letters and read could instead of cold or star instead of stair.

- Read words with the same letters but in a different sequence, like who instead of how, lots instead of lost, saw instead of was, or girl instead of grill.

- Confuse look-alike letters that differ in orientation, like b and d, b and p, n and u, or m and w.

- Substitute similar-looking words, like house for horse, even though they change the sentence’s meaning.

- Substitute a word that means the same thing but doesn’t look at all similar, like trip for journey or cry for weep.

- Misread, leave out, or add small words like an, a, from, the, to, were, are, and of.

- Leave out or change suffixes, reading need for needed, talks for talking, or soft for softly.

- Read out loud with a slow, choppy cadence. Their phrases aren’t smooth, and they often ignore punctuation.

- Be visibly tired after reading for only a short time.

- Reading comprehension is poor because they spend so much energy figuring out words. Their listening comprehension is usually heaps better.

- Have trouble tracking (following words and lines across pages), skipping words or whole lines of text as a result.

- Try to avoid reading or other close-up tasks and have plenty of excuses on hand for why they can’t read right now.

- Need a lot of snacking, bathroom, or resting time between very short bouts of actual reading.

- Complain of physical problems, like eyestrain, red or watery eyes, headaches, dizziness, or a stomachache, when they read.

- Squint, frown, rub their eyes, tilt their head, cover one eye to read or hold books too close to their eyes.

- Complain of words moving or running off the paper.

Signs of dyslexia in writing

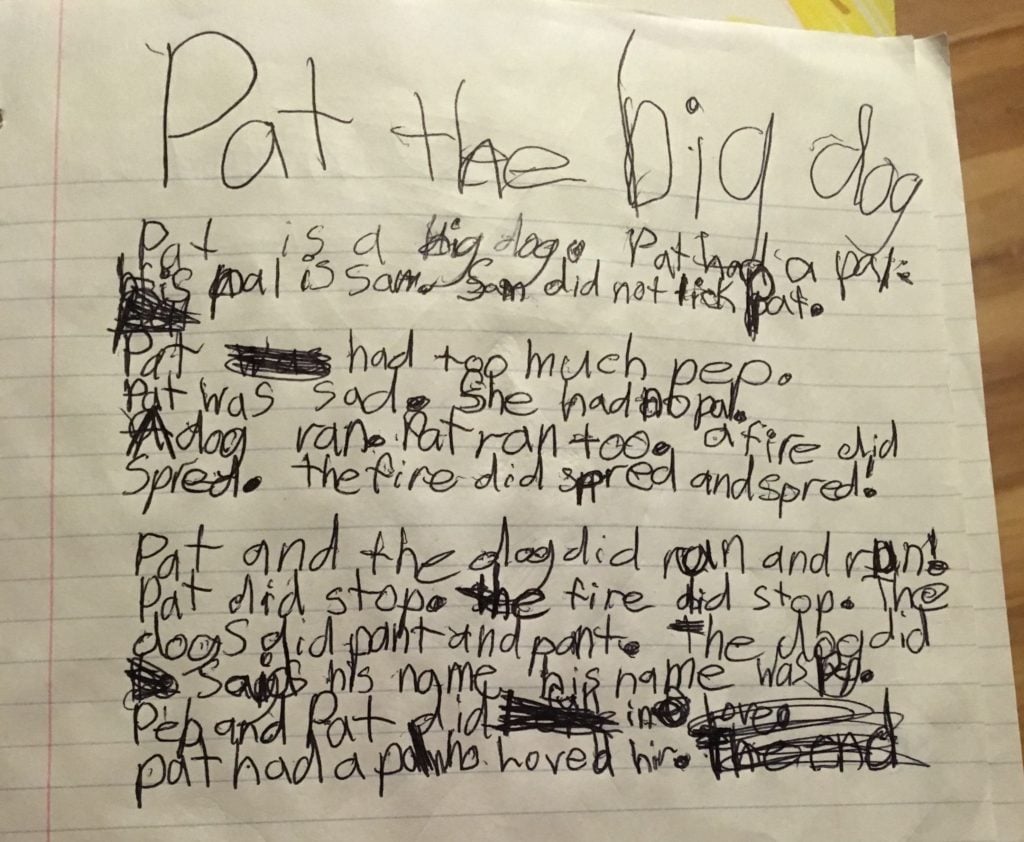

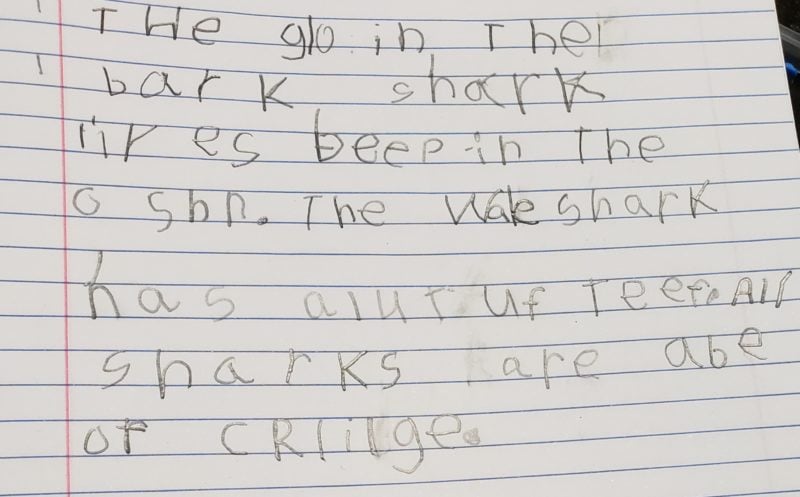

Children with dyslexia usually show a considerable difference between their ability to tell you something and write it down (Wood, 2005). They tend to:

- Avoid writing.

- Write everything as one continuous sentence.

- Struggle to understand punctuation, not using capitals or periods or using them randomly.

- Struggle to understand the difference between a complete sentence and a sentence fragment.

- Misspell many words even when they use only very simple ones and are “sure” they know how to spell the words.

- Mix up b and d, m, and n, and other look-alike letters.

- Take ages to write.

- Write illegibly.

- Use odd spacing between words. They may ignore margins completely and pack sentences tightly on the page instead of spreading them out.

- Use a mix of print and cursive and upper- and lowercase.

- Not notice their spelling errors. They read back what they wanted to say, not what they actually wrote.

- Use both hands for writing up to about age seven. Most children choose a dominant hand at about age five.

Signs of dyslexia in the classroom

If a child has dyslexia, their teacher should spot many reading, writing, and spelling errors listed above. Signs of dyslexia specific to the classroom may include:

- Noticeable and unexpected low achievement.

- Conspicuous disorganization.

- Distractibility or a short attention span.

- Persistent left/right confusion.

- Difficulty making sense of instructions.

- Difficulty remembering words and learning new words.

- Immature speech (such as “gween” for “green”).

- Inability to always understand what is said to them.

- Difficulty finding appropriate words in telling stories.

- Trouble with time, counting, and calculating.

- Difficulty sequencing days of the week and months of the year.

- Failure to finish work on time.

- Appearance of being lazy, unmotivated, or frustrated.

- Awkwardness or clumsiness.

Overcoming the signs of dyslexia

While children do not ‘outgrow’ dyslexia, it can be overcome with proper treatment. Below are success stories of children who overcame their dyslexia signs and symptoms and the difference it made to their lives:

Authored by Susan du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a reading specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.

References:

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed. revised). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Simos, P. G., Rezaie, R., Papanicolaou, A. C., & Fletcher, J. M. (2014). Does IQ affect the functional brain network involved in pseudoword reading in students with reading disability? A magnetoencephalography study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7(932).

Tanaka, H., Black, J. M., Hulme, C., Stanley, L. M., Kesler, S. R., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., Reiss, A. L., Gabrieli, J. D. E., & Hoeft, F. (2011). The brain basis of the phonological deficit in dyslexia is independent of IQ. Psychological Science, 22(11): 1442-51.

Wood, T. (2011). Overcoming dyslexia for dummies. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing, Inc.