Neuroscientists at MIT and Boston University have discovered that a basic mechanism underlying sensory perception is deficient in individuals with dyslexia, according to study published in Neuron. The brain typically adapts rapidly to sensory input, such as the sound of a person’s voice or images of faces and objects, as a way to make processing more efficient. But for individuals with dyslexia, the researchers found that adaptation was on average about half that of those without the disorder.

The difference may explain some of the challenges people with dyslexia experience, such as discerning speech in a noisy environment and learning to read. “Adaptation is something the brain does to help make hard tasks easier,” says first author Tyler Perrachione, assistant professor of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences at Boston University, who completed this research as a graduate student and post-doctoral fellow at MIT. “Dyslexics are not getting this advantage.”

Perrachione, who has a background in linguistics, wanted to investigate the theory that reading difficulties in dyslexia come from difficulties in associating sounds with written words. Working in the lab of lead investigator John Gabrieli, professor of Brain and Cognitive Science at MIT, he decided to investigate early, fundamental processes in the brain that could make this association difficult. “Part of the mystery of dyslexia is that the brain doesn’t have an area that evolved for reading,” says Gabrieli.

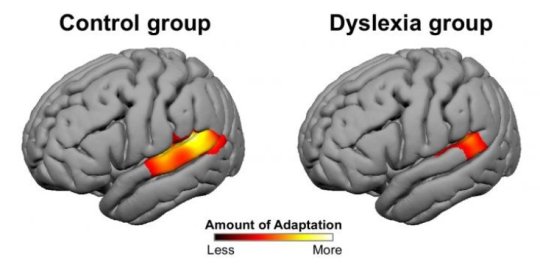

They zoomed in on the process of rapid neural adaptation. The researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine the brains of adults with and without dyslexia as they listened to voices. In some cases, the same voice spoke a series of words; in others, different voices spoke each word.

Brains typically adapt to a single, consistent voice within a second or two, but they don’t adapt to many different voices. As brains adapt, the fMRI measures of brain activity in relevant brain areas drop.

Individuals without dyslexia adapted to a consistent voice and not to multiple voices. But for dyslexics, brain activity remained high in both cases, suggesting that they did not adapt as much. Dyslexics with better reading skills showed greater adaptation levels. “Brains typically tune in and figure out what is consistent about a voice,” says Perrachione. “We saw much less adaptation in those with dyslexia group compared to typical readers.”

These results raised questions, since difficulty understanding speech is not seen in dyslexia. “If you were to talk to someone on the street, you’d have no idea if they were dyslexic or not,” says Perrachione.

So Perrachione and Gabrieli decided to look at adaption to visual stimuli, too. They recruited another group of individuals with and without dyslexia and examined adaptation to images of written words, faces, and objects, either in a series of different images or repeated images. Again they saw much less adaptation in participants with dyslexia.

The reduced adaptation was observed in the regions of the brain responsible for processing the stimuli in question. “This suggests that adaptation deficits in dyslexia are general, across the whole brain,” says Perrachione.

They repeated this experiment with yet another group of individuals, this time focusing on children aged 6 to 9 with and without dyslexia. The results were the same. Overall, the study involved over 150 individuals, and dyslexics on average had adaptation levels about half those of typical readers. “I am surprised by the magnitude of the difference,” says Perrachione. “In people without dyslexia, we always see adaptation, but in the dyslexics, the lack of adaptation was often really pronounced.”

Perrachione and Gabrieli speculate that dyslexics don’t struggle with processing of heard speech or seen objects and faces because human brains evolved to process these inputs. The systems that perform this processing are likely very robust. “The brain devotes a lot of infrastructure to solving these problems, and has multiple routes,” says Perrachione. “Adaptation is just one of the things that helps take the load off.”

But reading is a different story. It is a learned skill that requires multiple regions of the brain to work together, potentially with the harmony and complexity of a Rube Goldberg machine, says Perrachione. As rapid neural adaptation deficits simultaneously affect auditory and visual processing during reading, they may compound to make reading very difficult. “We have to see letters, map them onto words, map those to sounds, and connect them to semantics,” says Perrachione. “There are lots of places for things to go wrong.”

It isn’t known yet exactly where things do go wrong as a result of deficits in rapid neural adaptation. “This study presents strong evidence for a foundational brain difference in dyslexia, but it isn’t clear how to bridge that to the specific properties of reading,” says Gabrieli. “It opens up as many questions as it answers.”

.

.

.