Table of contents:

- What is visual dyslexia?

- Symptoms and characteristics

- Causes of visual dyslexia

- Treatment of visual dyslexia

What is visual dyslexia?

The term dyslexia was coined from the Greek words dys, meaning ill or difficult, and lexis, meaning word. It is used to refer to persons for whom reading is simply beyond their reach. Spelling and writing are usually included due to their close relationship with reading.

Dyslexia is considered to be a neurological disorder in the brain that causes information to be processed and interpreted differently, resulting in reading difficulties.

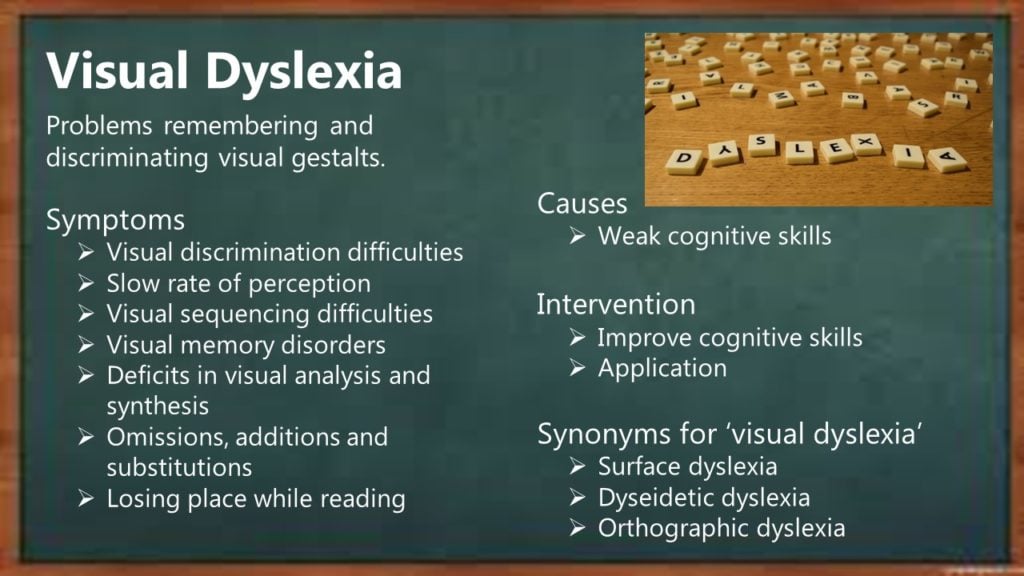

Scholars often use the terms visual dyslexia and auditory dyslexia to describe two main types of dyslexia. Visual dyslexia is a subtype of dyslexia that refers to children who struggle with reading because they have problems remembering and discriminating visual gestalts. Synonyms are surface dyslexia, dyseidetic dyslexia, and orthographic dyslexia.

Symptoms and characteristics

Among the manifestations which characterize visual dyslexia, according to Saroj D. Sutaria (Specific Learning Disabilities: Nature and Needs), are visual discrimination difficulties; slow rate of perception; visual sequencing difficulties; visual memory disorders; deficits in visual analysis and synthesis; omissions, additions, and substitutions; and losing place while reading.

1.) Visual discrimination difficulties

The child who has difficulties in visual discrimination are unable to recognize similarities and differences between letters and words. They especially find difficulty making differentiation between similar-looking letters such as /n/, /m/, /u / or /b/, /d/, /p/, /q/, etc., or between words such as /hat/, /hot/, /hate/ or /pug/, /bug/, or /no/, /on/, etc. Recognizing letters requires the ability to make rather fine discriminations which, in turn, depends on the ability to make gross visual discriminations.

Three of the more common forms of discrimination problems to be noted in the learning disabled include reversals, rotations, and inversions:

- Reversals — The most common problem cited to exemplify reversals is the confusion between /b/ and /d/. This confusion represents the exact mirror-imaging that some learning disabled experience. When words containing /b/ or /d/ are read, they are frequently misread because they have been perceived oppositely, as, for example, /bad/ for /dab/, /big/ for /dig/, etc., or vice versa.

. - Rotations — The form of the letter is rotated so that it is perceived differently; for example, the letter /b/ may be read as /p/ because the child has rotated the axis from its original upward direction to a downward direction, or confusing /b/ for /q/ which would be a rotation of a greater magnitude, with the axis seen as going down the opposite side.

. - Inversions — A variation of both reversal and rotation is an inversion. The letter form is inverted. Thus, the child may confuse /n/ with /u/ and /m/ with /w/, etc.

.

2.) Slow forming of visual perceptions

The child’s oral reading is slow and labored. This is especially so because the child cannot form visual perceptions at the normal age rate. As a result, the child may be observed to look at a visual stimulus (fixation) a long time or repeated times before they will respond to it. There is also a greater tendency to regress to a previously recognized form while the hesitancy or uncertainty lasts.

3.) Visual sequencing difficulties

The child who is unable to retain the visual sequence in short-term memory long enough to be able to recall it or who, because of a lack of left-to-right directional tracking with the eyes, misperceives the order in which the letters appear in words, will read them incorrectly — for example, reading /god/ for /dog/, /was/ for /saw/, /nap/ for /pan/, etc. This is not to suggest that the sequencing disruption affects only the first and last consonants. Sequencing disruption can take place in any position. For example, the word /story/ could be read as /stroy/, /tow/ as /two/, /kitchen/ as /chicken/, etc.

In compound words, entire syllables could be reversed: for instance, /yardstick/ read as /stickyard/, /horseshoe/ as /shoehorse/, etc.

4.) Visual memory disorders

Deficits in visualizing letters and words, that is, what they look like in their physical characteristics, affect the ability to develop sight recognition of words. A child with a poor visual memory may approach each word as though for the first time. Even when words are repeated, the child cannot recall them. The child cannot process short- and long-term storage and retrieval efficiently to make the needed associations between the word’s visual and auditory or linguistic aspects. In other words, visual imagery is poor. This has a serious consequence because so many words in the English language cannot be sounded out. The tendency to guess at the word from its size is often observed.

5.) Deficits in visual analysis and synthesis

To read fluently, the child must recognize words as units, each having a separate entity or a configuration. Within each word, the child must recognize each letter and its relation to the others in the word. The child with difficulty in visual analysis would be unable to find a given letter in the alphabet, a smaller word in a larger word, a word in a sentence, a sentence in a paragraph, etc., primarily because of the array of competing visual stimuli and the child’s difficulty in breaking the stimuli down into component parts. In other words, the foreground-background disturbance interferes with the child’s ability to succeed in the task.

Visual synthesis requires putting the pieces together to compose a whole. Sometimes a few pieces may be missing. Nonetheless, if enough stimulus is present to provide the needed clues to the missing parts, the child should be able to guess the word. Unfortunately, a child with difficulties in visual synthesis cannot do so. In other words, the child cannot use partial information to make a correct guess. Further, failure to perceive words as entities results in attention to single or isolated letters rather than words. Such a child also has problems combining two small words to form compound words, putting syllables together to make a word, unscrambling letters to make a word, and/or unscrambling words to make a sentence.

6.) Omissions, substitutions, additions

Perhaps the most common omission in a young reading-disabled child’s reading is the punctuation mark. The child’s oversight of the punctuation marks causes their reading to lack inflection and variation. The child’s pauses may be several, but they usually occur at the wrong places because of hesitations.

In addition to missing punctuation, many smaller words, such as articles, are frequently missed. Sometimes, parts of words, especially the endings or descriptive and more difficult words, may be missed. For instance, the child may read /A boy went walk/ for /A boy went walking/ or /a dog/ for /a fierce dog/, etc.

They also tend to substitute letters and sometimes whole words. For example, instead of reading /father/, the child might read /dad/, which is a meaningful linguistic substitution but nonetheless an error from the visual decoding aspect. Critchley noted substitutions of opposite meanings, such as /this/ for /that/, /his/ for /her/, etc.

Additions are also frequently noted. For instance, if the story starts with /Once there was/ the child reads /Once upon a time there was/, etc.

7.) Losing place while reading

The child’s difficulty in making left-to-right tracking movements has already been noted. We have seen how this disrupts the sequencing of letters and syllables in words. This difficulty also causes the child to lose their place in reading. The child may skip to the next line of print, often unaware that they have done so, or have difficulty switching from one line to the next. The inability to keep place also shows up when someone else is reading, and the learning disabled is required to follow along.

Causes of visual dyslexia

While there are other causes, the most common cause of dyslexia is that the brain-based skills that underpin reading and spelling have not been mastered properly.

Learning is a stratified process. One step needs to be mastered well enough before subsequent steps can be learned. This means that there is a sequence involved in learning. It is like climbing a ladder; you will fall if you miss one of the ladder’s rungs. Likewise, if you miss out on one of the important steps in the learning process, you will be unable to master subsequent steps.

A simple and practical example is that one has to learn to count before it becomes possible to learn to add and subtract. Therefore, if one tries to teach a child to add and subtract before they have been taught to count, one will quickly discover that no amount of effort will ever succeed in teaching the child these skills.

This principle is also of great importance on the sports field. If we go to a soccer field to watch the coach at work, we shall soon find that he spends a lot of time drilling his players in basic skills, like heading, passing, dribbling, kicking, etc. The players most proficient at these basic skills usually turn out to be the best in an actual game.

In the same way, there are also specific skills and knowledge that children must acquire first, before it becomes possible for them to become good readers.

While phonological processing skills and auditory memory are foundational to learning phonics, visual processing skills (such as spatial relations and form discrimination), visual memory, visual-spatial memory, and rapid recall are foundational to remembering and discriminating visual gestalts. Rapid recall refers to the speed with which the names of symbols (letters, numbers, colors, or pictured objects) can be retrieved from long-term memory. This process is often termed rapid automatized naming (RAN), and people with visual dyslexia typically score poorer on RAN assessments than typical readers.

Treatment of visual dyslexia

The good news is that weaknesses in cognitive skills can be attacked head-on; it is possible to strengthen these mental skills through training and practice. Edublox’s Development Tutor aims to strengthen underlying cognitive skills, including visual processing skills, visual memory, and rapid naming. In addition, children receive live online reading and spelling lessons. Click here to book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs.

Carole Derrick, a teacher in the US, reported: “After working for 6 weeks with Allen who is functioning at a nonreader level with a fragile self-esteem, I have witnessed academic progress as well as a boost in self-confidence… Allen’s difficulties with dyslexia have improved. In the first 3 weeks of the program, Allen was reversing letters frequently (b for d; on for no). If such reversals occur during the 6th week, he usually corrects himself.”

Mrs. K. G. Robertson wrote: “My son has tried the following: Remedial teaching, extra lessons and occupational therapy. Unfortunately, although there was an improvement my son’s problem remained. This resulted in him avoiding any reading and writing. He developed behavioral problems. He was ashamed of his dyslexia. We started your program and within two months he improved to the extent that he will pick up and read a newspaper or magazine of his own free will – without prompting. He has stopped reversing and substituting the letters b, p, and d. He writes messages freely. Your program has made an immense difference.”

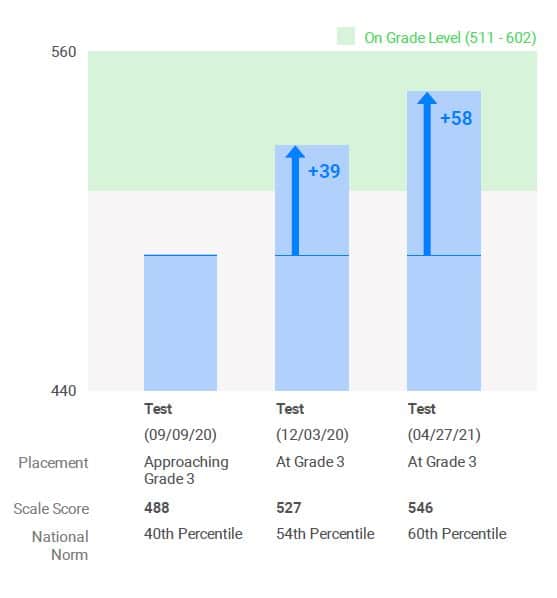

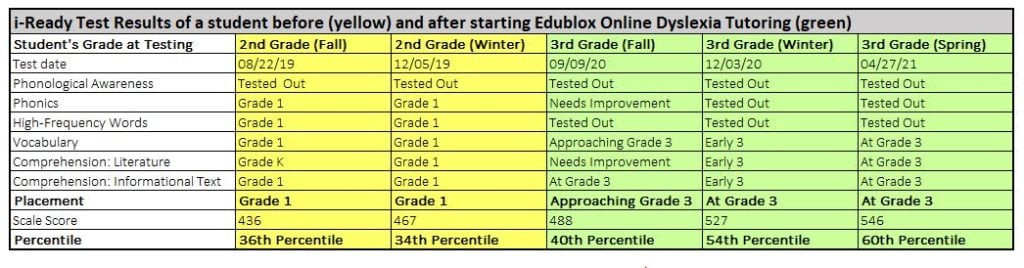

Table 1 shows the summarized i-Ready test results of a student with visual dyslexia after three months of twice-weekly tutoring going forward. In Table 2, one can also see his comprehensive i-Ready scores before (yellow) and after (green) he started Edublox training. In summary, in eleven months, the student progressed from approximately one year behind in most reading areas, excluding phonological awareness (34th percentile), to average or above average in all reading areas (60th percentile).

.

Visual dyslexia – key takeaways

Authored by Susan du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years of experience in the learning disabilities field.