Table of contents:

- Introduction

- What is a math learning disability?

- Why does numeracy matter?

- How common are math learning disabilities?

- What are the symptoms?

- What causes math learning disabilities?

- How can math learning disabilities be treated?

Introduction

Mathematics is often called the universal language. Whether you are trading at a market stall in Nairobi, navigating a train schedule in Tokyo, or sending a spacecraft to Mars, numbers are woven into every aspect of life. Math is not just an academic subject confined to classrooms; it is an essential skill for survival, decision-making, and participation in society. From balancing a household budget to calculating medication dosages, mathematical thinking is unavoidable.

Every career path, from sheepherder to software engineer, relies on math in some form. A farmer must measure land and track livestock; a nurse must calculate drug dosages; an entrepreneur must interpret sales figures; and a scientist must work with complex formulas. Mathematics also underpins technological progress: computers, smartphones, GPS navigation, and even the algorithms that guide online shopping depend on mathematical reasoning.

Because of this, a difficulty with math is not a trivial problem. The effects of math failure ripple far beyond poor test scores. Students who consistently struggle may see doors to promising careers — like medicine, engineering, or finance — close before they even open. Low numeracy can undermine confidence, limit vocational options, and restrict independence in daily life. It can prevent individuals from managing money effectively, interpreting contracts, or even arriving at the right place at the right time.

Globally, the stakes are high. Studies have shown that weak numeracy skills are associated with higher unemployment rates, lower wages, poorer health outcomes, and increased reliance on welfare systems. At a societal level, widespread math difficulties create economic costs measured in billions. At a personal level, they erode self-esteem, create anxiety, and can foster social isolation.

This is why identifying and addressing math learning disabilities is so important. While many children and adults experience occasional difficulty with mathematics, a math learning disability — often referred to as dyscalculia — is something more persistent and severe. Like dyslexia in reading, dyscalculia interferes with the ability to process numbers and mathematical concepts despite adequate intelligence and opportunity.

In this article, we will explore what math learning disabilities are, why numeracy matters, how common these difficulties are, the symptoms and causes, and how they can be treated. Understanding dyscalculia is the first step toward ensuring that every learner has the chance to unlock the world of numbers — and with it, greater confidence, opportunity, and independence.

What is a math learning disability?

A math learning disability is not simply “being bad at math.” Almost everyone struggles with mathematics at some point — whether it’s memorizing multiplication tables, understanding fractions, or solving algebraic equations. But for some individuals, these struggles go far beyond the ordinary frustrations of learning. Despite having normal intelligence, receiving adequate instruction, and putting in effort, they consistently fail to grasp and retain mathematical concepts. This persistent difficulty is what defines a math learning disability.

The formal diagnostic term used in the DSM-5 (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) is Specific Learning Disorder with impairment in mathematics. To qualify for this diagnosis, a person’s mathematical achievement must be significantly below what is expected for their age, and the difficulties cannot be explained by an intellectual disability (IQ below 70), lack of schooling, or other external factors.

In everyday language, the word most often used is dyscalculia, derived from the Greek roots dys (“bad”) and calculia (“to calculate”), meaning literally an inability to calculate. Dyscalculia is sometimes referred to as “math dyslexia,” though this term can be misleading, since the underlying difficulties differ from those in reading.

Other terms have also been used to capture the variety of challenges people face with math. These include:

- Developmental dyscalculia – difficulties present from early childhood.

- Mathematical learning difficulty – a broader umbrella term that covers milder problems as well as severe disability.

- Arithmetic learning disability – focusing specifically on problems with arithmetic operations.

- Number fact disorder – emphasizing the inability to memorize and recall basic math facts.

- Number dyslexia – an informal but increasingly popular term highlighting similarities with reading difficulties.

Although these terms vary, they all point to the same core reality: a math learning disability disrupts the ability to acquire, process, and apply numerical knowledge.

It is important to recognize that dyscalculia is not caused by laziness or lack of effort. Nor does it mean a child (or adult) cannot succeed academically or professionally. Many individuals with math learning disabilities are highly intelligent, creative, and capable in other domains. Some even excel in subjects that appear to require little math, such as literature, art, or history. However, without proper intervention, their math difficulties can persist into adulthood, making everyday tasks — from budgeting to interpreting timetables — significantly more challenging than they should be.

In short, a math learning disability is a specific, enduring, and genuine condition that requires understanding, support, and targeted teaching approaches. Naming it and recognizing it are the first steps toward helping learners overcome its challenges.

Why does numeracy matter?

Numeracy is more than the ability to perform calculations; it is the capacity to make sense of numbers in everyday life. It involves understanding quantities, recognizing relationships, interpreting data, and applying mathematical reasoning to real-world situations. In this sense, numeracy is as fundamental as literacy. While literacy allows us to read words, numeracy allows us to “read the world” in numerical form.

Strong numeracy skills equip individuals to make sound decisions. Whether weighing the risks and benefits of a medical treatment, comparing interest rates on loans, or interpreting a news graph about unemployment, numeracy enables people to engage critically rather than passively. It allows citizens to participate in democracy, where statistics often underpin debates about education, health, crime, or the economy.

The consequences of weak numeracy, on the other hand, are profound. Research has shown that low numeracy correlates with:

- Reduced employment prospects – people with poor math skills are more likely to work in low-paid, insecure jobs and less likely to receive promotions.

- Financial vulnerability – difficulties with percentages, interest rates, and budgeting often lead to debt, poor savings habits, or susceptibility to scams.

- Health challenges – understanding prescriptions, dosage instructions, and medical statistics requires basic numerical competence. Patients with low numeracy may struggle to follow treatment plans effectively.

- Greater reliance on others – adults with dyscalculia often report depending heavily on spouses, friends, or technology for tasks that involve numbers, reducing independence.

.

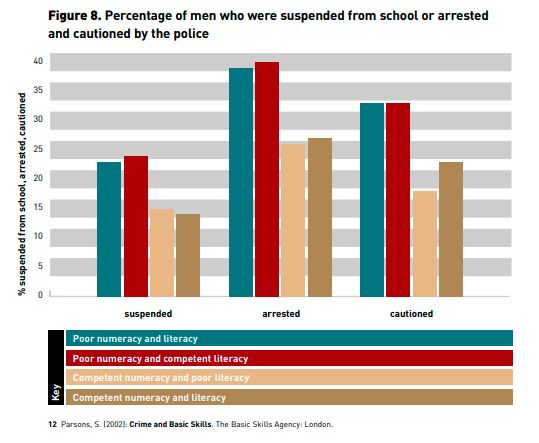

The economic impact is staggering. A large-scale UK study found that individuals with poor numeracy earned significantly less and were more prone to unemployment than peers with similar literacy skills (Parsons & Bynner, 2005). Another report estimated that low numeracy costs the UK economy over £20 billion annually in lost productivity and increased welfare needs. In the United States, analysts estimate that low literacy and numeracy combined result in annual losses exceeding $200 billion, due to unemployment, crime, and reduced tax revenues (Pro Bono Economics & National Numeracy, 2014).

However, beyond statistics, the personal toll is heavy. Adults who never gain confidence in math may experience anxiety in daily situations: splitting a restaurant bill, converting currencies when traveling, or helping their children with homework. Some avoid activities that might expose their difficulties, leading to embarrassment or social withdrawal.

Math learning disabilities can also lead to social isolation in subtler ways. A child who cannot keep score in a soccer match or follow the rules of a board game may feel excluded from play. An adult who struggles with timetables or directions may find it challenging to arrive at the right place at the right time. Some adults with dyscalculia even report that they never learned to drive, because managing distances, speeds, and time calculations felt overwhelming (Hornigold, 2015).

In short, numeracy matters because it is inseparable from modern life. It shapes opportunities, independence, and well-being — yet too often, those with math learning disabilities remain invisible. Recognizing the seriousness of dyscalculia is a necessary first step toward change.

How common are math learning disabilities?

Math learning disabilities are far more common than many people realize. Among students classified as having learning disabilities, difficulties with mathematics are as prevalent as difficulties with reading. According to McLeod and Crump, roughly half of students with learning disabilities require supplemental support in math.

Estimates of dyscalculia prevalence vary, depending on the definitions and diagnostic tools used, but research consistently suggests that between 3% and 7% of the population experiences severe, persistent math difficulties. Some studies report rates as high as 10% when broader definitions are used. This means that in a typical classroom of 30 children, at least one or two may struggle with a genuine math learning disability.

However, compared to dyslexia, which has received decades of public and research attention, dyscalculia remains relatively invisible. Despite the far-reaching importance of numeracy, public awareness is low. Parents, teachers, and policymakers widely recognize dyslexia, but dyscalculia has lagged in both recognition and funding. Between 2000 and 2010, the U.S. National Institutes of Health spent more than $100 million on dyslexia research but only about $2 million on dyscalculia (Butterworth et al., 2011). This imbalance has slowed scientific progress and left many learners without adequate support.

The lack of awareness also affects diagnosis. Many children with math learning disabilities go undetected, often dismissed as “lazy,” “careless,” or “just not good at math.” Teachers may recognize struggling readers more readily than struggling mathematicians, and school systems often lack formal screening tools for dyscalculia. As a result, countless children grow up without ever receiving the help they need.

International comparisons suggest that the problem is widespread. Surveys conducted across Europe, North America, and Asia indicate that math difficulties transcend cultural, linguistic, and educational boundaries. Low numeracy is not confined to one country or region — it is a global challenge with consequences for both individuals and economies.

In short, math learning disabilities are common, under-recognized, and under-researched. Increasing awareness and improving diagnostic practices are essential steps toward ensuring that struggling learners are identified early and given effective interventions.

What are the symptoms?

Math learning disabilities manifest in a variety of ways, and not all learners show the same profile of difficulties. However, research and classroom experience highlight several common patterns. These symptoms may appear in childhood and often persist into adolescence and adulthood.

1. Core arithmetic difficulties

- Persistent trouble learning and recalling basic math facts (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division).

- Reliance on immature or inefficient strategies, such as drawing dots or counting on fingers long after peers have moved on to faster methods.

- Long completion times on even simple problems, often with high error rates.

- Weak ability to perform mental arithmetic.

- Difficulty estimating whether an answer is reasonable (e.g., not recognizing that 54 × 7 cannot possibly equal 360).

- Poor number sense, such as failing to see relationships (e.g., not realizing that 29 + 30 + 31 equals 3 × 30).

2. Symbolic and language-related difficulties

- Confusing or misinterpreting the symbols +, −, ÷, and ×.

- Difficulty understanding math words like “plus,” “minus,” “divide,” “altogether,” or “more than.”

- Struggling with word problems, even when reading ability is intact.

- Difficulty generalizing knowledge (e.g., knowing that 3 + 4 = 7 but not applying it to 30 + 40 = 70 or 3 cm + 4 cm = 7 cm).

3. Visual-spatial and perceptual difficulties

- Reversing or transposing digits (writing 63 for 36, or 875 for 785).

- Trouble aligning numbers correctly in multi-digit problems or placing decimals in the right position.

- Difficulty recognizing or extending patterns (e.g., not noticing the sequence in the 5-times table: 5, 10, 15, 20, 25…).

- Struggling to subitize — instantly recognize small quantities without counting — even with sets of two or three objects.

.

4. Time and measurement difficulties

- Struggling with measurements of money, weight, or distance — for example, checking change at a store or comparing prices.

- Difficulty learning to read both analog and digital clocks.

- Struggling to understand basic time concepts, such as “one day = 24 hours” or “60 minutes = one hour.”

- Chronic problems with time management: being late, forgetting schedules, or underestimating how long tasks will take.

- Difficulty remembering dates and historical timelines.

.

5. Everyday life challenges

- Inability to keep score or follow the rules in games and sports.

- Struggling to handle money, budgets, or bills.

- Difficulty with navigation and directions (e.g., arriving at the wrong place or being late due to misjudged travel times).

- Avoiding number-related situations, which can lead to frustration, embarrassment, or social isolation.

- Some adults report that they never learned to drive because of the numerical demands of managing speed, distance, and time simultaneously.

These symptoms affect not only classroom performance but also everyday functioning. While occasional math struggles are common in many children, math learning disabilities are marked by persistent, severe, and resistant difficulties that do not resolve with typical instruction. Recognizing these signs early is the first step toward appropriate support and intervention.

What causes math learning disabilities?

Math learning disabilities do not have a single cause. Instead, they arise from a combination of brain-based differences, genetic influences, cognitive weaknesses, and educational experiences. While the profile varies from child to child, researchers generally agree that biology lays the foundation, while environmental and emotional factors shape how the difficulties are expressed.

1. Brain-based causes

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that children with dyscalculia show differences in the way their brains process numbers.

- The intraparietal sulcus (IPS), a region in the parietal lobe, is consistently linked to number sense and magnitude representation. Structural and functional differences in this region have been found in individuals with dyscalculia.

- Connectivity differences between the IPS and other brain regions (such as the frontal lobe, necessary for working memory and problem-solving) may also contribute.

- These differences are not the result of poor teaching or lack of effort; they reflect how the brain is wired to process numerical information.

2. Genetic influences

Like dyslexia, dyscalculia often runs in families. Twin and family studies suggest a heritable component, with genetics accounting for a significant portion of the variance in mathematical ability. Researchers have identified overlaps between genes linked to dyslexia and those associated with math difficulties, which helps explain why many children struggle with both reading and math.

- For example, studies on identical twins show higher concordance rates for math learning difficulties than fraternal twins, underscoring the role of heredity.

- Genetic influences do not determine destiny, but they do increase susceptibility, especially when combined with environmental challenges.

3. Cognitive skill weaknesses

Even with genetic and brain-based vulnerabilities, the immediate challenges learners face are often rooted in cognitive skills that underpin math performance. These include:

- Perception (figure-ground differentiation, visual and auditory discrimination, spatial orientation).

- Memory (short-term, working, long-term, and visual memory).

- Logical reasoning enables problem-solving and the transfer of knowledge to new contexts.

For example, Szűcs et al. (2013) found that children with dyscalculia performed poorly on visuospatial memory tasks, such as recalling the location of items in a grid. Such weaknesses make it harder to remember instructions, hold numbers in mind during calculations, and build a store of arithmetic facts.

4. Mathematical language and skills

Mathematics functions as a unique language with its own vocabulary and symbols. Children with math learning disabilities may struggle to:

- Understand terms like “equals,” “before,” or “less than.”

- Interpret and consistently use symbols like +, −, or ×.

- Solve word problems, where success requires translating verbal language into mathematical operations.

Furthermore, mathematics is sequential. Each new skill builds on a previous one. If a child has not mastered counting, they cannot progress confidently to addition or subtraction. Gaps in the learning sequence can therefore block progress at multiple points.

5. Math anxiety (supplementary factor)

While not a root cause, math anxiety often develops alongside math learning disabilities and can worsen their effects. Children who repeatedly fail at math may begin to associate the subject with fear and dread. Ashcraft and Faust (1994) describe math anxiety as feelings of tension, helplessness, and disorganization in the face of numerical tasks.

- Anxiety can impair performance during tests or lessons, creating a cycle of failure and avoidance.

- Students with math anxiety may rush through tasks, sacrifice accuracy for speed, or shut down when faced with numerical challenges.

- Over time, this emotional overlay compounds the original cognitive or brain-based difficulties.

Math learning disabilities arise from a complex interplay of brain-based differences, genetic predispositions, and weaknesses in cognitive foundations, including memory, perception, and reasoning. Challenges with mathematical language and skill sequences then magnify these factors. Emotional reactions like math anxiety, while not primary causes, often arise as secondary effects that intensify the struggle.

By understanding these layered causes, educators and parents can view dyscalculia not as laziness or a lack of effort, but as a genuine and multifaceted condition that requires targeted intervention.

Can math learning disabilities be treated?

For many years, math learning disabilities were viewed as lifelong barriers that could not be overcome, only managed. Today, research and experience show a different picture: with the right interventions, children and adults with dyscalculia can make meaningful progress. Treatment does not erase the underlying vulnerabilities, but it equips learners with the tools, strategies, and skills they need to succeed.

The stratified nature of learning

Learning is a stratified process — it builds in layers. Just as a child must crawl before walking and walk before running, mathematical skills must be acquired in a logical order. If earlier steps are missing, later steps cannot be mastered.

Think of basketball. No one begins by mastering complex plays or slam dunks. First, players must learn to dribble, pass, and shoot. These foundational skills, practiced repeatedly, create the base upon which more advanced techniques can develop.

Math is no different. A learner must first develop the cognitive foundations — such as visual memory, sequencing, and attention — before higher-order operations like fractions, algebra, or problem-solving can make sense. When these foundations are weak, gaps appear, and frustration sets in.

Building the foundations

The first step in treatment is strengthening the cognitive skills that underlie mathematical learning. As these abilities improve, the “mental workspace” required for math expands, allowing learners to hold numbers in mind, follow multi-step problems, and recognize patterns.

Mastering math language and skills

Students must catch up sequentially on mathematical language and skills. Just as one cannot learn to subtract before learning to count, math concepts must be taught in a carefully ordered progression.

Equally important is teaching an in-depth understanding of math terminology. Words like “sum,” “difference,” “quotient,” or “factor” must be explicitly explained, practiced, and reinforced until they become part of the learner’s everyday vocabulary.

Addressing the emotional side

For many students, years of failure in math have created anxiety and avoidance. Even if anxiety is not the root cause of dyscalculia, it can block learning if not addressed. Effective treatment includes encouragement, incremental successes, and a supportive environment that rebuilds confidence. As students experience progress, fear begins to give way to resilience and motivation.

How Edublox helps

At Edublox, we provide structured support for students with mild to severe math learning disabilities. Our approach combines cognitive training, sequential skill teaching, and confidence-building:

- Developing foundational skills: We strengthen visual processing, attention, working memory, sequencing, and reasoning — the essential building blocks of mathematical thinking.

- Teaching math skills sequentially: We ensure that students master counting before moving on to addition, addition before subtraction, and so forth, gradually toward fractions, decimals, and beyond.

- Deepening understanding of math language: We teach not only how to calculate but also how to interpret and use mathematical terminology with accuracy.

This integrated approach has helped thousands of learners transform their relationship with math — moving from confusion and fear to competence and independence.

Summary

Math learning disabilities are not a dead end. With targeted interventions that address both cognitive foundations and sequential math skills, students can make significant progress. Like the basketball player who first masters dribbling and passing, learners with dyscalculia can build the skills needed for success — one step at a time.

With the right intervention, math learning disabilities don’t have to hold a child back. Progress is possible, and confidence can be rebuilt. Book a free consultation to explore how Edublox can help your child succeed in math. Also watch our testimonial playlist below:

Key takeaways

Math Learning Disabilities: Symptoms, Causes, Treatment was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyscalculia specialist and with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities.

Bibliography and references:

- Ashcraft, M. H., & Faust, M. W. (1994). Mathematics anxiety and mental arithmetic performance: An exploratory investigation. Cognition and Emotion, 8(2), 97–125.

- Butterworth, B., Varma, S., & Laurillard, D. (2011). Dyscalculia: From brain to education. Science, 332(6033), 1049–1053.

- Butterworth, B., & Yeo, D. (2004). Dyscalculia guidance: Helping pupils with specific learning difficulties in maths. London: David Fulton Publishers.

- Chinn, S. J. (2004). The trouble with maths: A practical guide to helping learners with numeracy difficulties. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Cockcroft, W. (1982). Mathematics counts: Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the teaching of mathematics in schools under the chairmanship of W. H. Cockcroft. London: HMSO.

- Faust, M. W., Ashcraft, M. H., & Fleck, D. E. (1996). Mathematics anxiety effects in simple and complex addition. Mathematical Cognition, 2(1), 25–62.

- Hornigold, J. (2015). Dyscalculia pocketbook. Alresford, Hampshire: Teachers’ Pocketbooks.

- McLeod, T. M., & Crump, W. D. (1978). The relationship of visuospatial skills and verbal ability to learning disabilities in mathematics. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 11(1), 67–70.

- Mercer, C., & Pullen, P. (2008). Students with learning disabilities (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Parsons, S., & Bynner, J. (2005). Does numeracy matter more? National Research and Development Centre for Adult Literacy and Numeracy.

- Price, G., & Ansari, D. (2013). Dyscalculia: Characteristics, causes, and treatments. Numeracy, 6(1).

- Pro Bono Economics & National Numeracy (2014). Cost of outcomes associated with low levels of adult numeracy in the UK.

- Rosselli, M., Matute, E., Pinto, N., & Ardila, A. (2006). Memory abilities in children with subtypes of dyscalculia. Developmental Neuropsychology, 30(3), 801–818.

- Rubinsten, O., & Tannock, R. (2010). Mathematics anxiety in children with developmental dyscalculia. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 6, 46.

- Szűcs, D., Devine, A., Soltesz, F., Nobes, A., & Gabriel, F. (2013). Developmental dyscalculia is related to visuo-spatial memory and inhibition impairment. Cortex, 49(10), 2674–2688.