Math literacy is essential for survival in modern society. Everyday tasks such as paying bills or budgeting for daily expenses all have to do with numbers. Every job, from the rocket scientist to the sheepherder, requires math. In addition, decisions in life are often based on numerical information: to make the best choices, we need to be numerate.

There is a widespread misunderstanding of the importance of math in everyday life and a lack of appreciation of how vital math learning is for young children.

Mathematics plays a significant role in a child’s development and helps children make sense of the world around them. Children between the age of one to five years old are beginning to explore patterns and shapes, compare sizes and count objects. More advanced mathematical skills are based on this early math foundation — just like a house is built on a solid foundation.

Despite the importance of numeracy, math learning disabilities — better known as dyscalculia — have received less attention than dyslexia. For example, between 2000 and 2010, the NIH spent $107.2 million funding dyslexia research but only $2.3 million on dyscalculia (Butterworth et al., 2011).

We investigate the characteristics, symptoms, and signs of dyscalculia.

Table of contents:

- What is dyscalculia?

- Characteristics, symptoms, and signs of dyscalculia

- Dyscalculia symptoms and signs by age

- Key takeaways

What is dyscalculia?

Dyscalculia is a specific learning difficulty characterized by severe and persistent impairment in mathematics, including difficulties using numbers and quantities, simple arithmetic, and counting.

Dyscalculia differs from the ordinary experience of “being bad at math.” Many people may find trigonometry difficult. Dyscalculics, however, may be unable to solve simple problems such as 7+2 or 5×3.

These difficulties are below what is expected for the individual’s chronological age and are not caused by poor education or intellectual deficits. The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) uses the term ‘Specific Learning Disorder with impairment in mathematics.’

Often thought of as the mathematical counterpart to dyslexia, people with dyscalculia struggle in everyday life, and their career choices are limited.

Characteristics, symptoms, and sign of dyscalculia

The most generally agreed-upon feature of children with dyscalculia is difficulty learning and remembering arithmetic facts.

The second feature of children with dyscalculia is difficulty executing calculation procedures, with immature problem-solving strategies, long solution times, and high error rates.

In addition, poor number sense and subitizing are core deficits.

- Number sense refers to a person’s ability to use and understand numbers.

People with good number sense understand how numbers relate to one another and are flexible in the approaches and strategies they use to perform calculations. They will, for instance, see that 29 + 30 + 31 is the same as 3 x 30 and will quickly work out the answer.

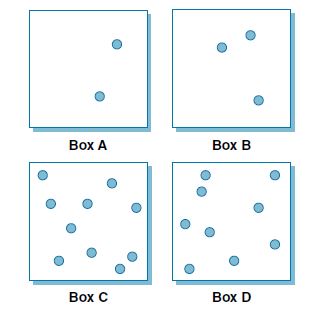

- Subitizing is the ability to instantly recognize the number of objects without actually counting them.

Most people can subitize up to six or seven objects. However, a child with dyscalculia may find this very hard and may need to count even small numbers of objects. For example, if they are presented with two objects, they may count them rather than just knowing there are two.

Clements (1999) describes two types of subitizing: perceptual and conceptual.

- Perceptual subitizing involves recognizing a number without using other mathematical processes, just as you did when looking at Boxes A and B.

- Conceptual subitizing allows one to know the number of a collection by recognizing a familiar pattern, such as the spatial arrangement of dots on the faces of dice or domino tiles.

Other symptoms and signs of dyscalculia include:

- Poor understanding of the signs +, -, ÷, and x; or may confuse these mathematical symbols.

- Difficulty with addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, or may find it challenging to understand the words “plus,” “add,” and “add-together.”

- Immature strategies such as counting all instead of counting on. The child may work out 137 + 78 by drawing 137 dots and then 78 dots and then counting them all.

- Difficulty with times tables.

- Poor mental arithmetic skills.

- Trouble with a calculator due to difficulties feeding in variables.

- Inability to notice patterns. The world of math is full of patterns, and the ability to see, predict and continue patterns is a key math skill. Take the 5 x table sequence, for example, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, et cetera. It is a clear pattern, but a student with dyscalculia may not spot it readily.

- Inability to generalize. Being able to generalize makes life so much simpler in math, but a dyscalculic student may find this very hard. They might not see that knowing that 3 + 4 = 7 means they also know that 30 + 40 = 70, or even that 3 inches + 4 inches = 7 inches.

- Difficulty with everyday tasks like checking change.

- Difficulty keeping score during games. People with dyscalculia may lose track of whose turn it is during games, like cards and board games. They may have limited strategic planning ability for games like chess.

- Children with dyscalculia may experience directional confusion, i.e., have difficulty discriminating left from right, and north, south, east, and west. They may have a poor memory for remembering learned navigational concepts: starboard and port, longitude and latitude, horizontal and vertical, and so on.

- They may reverse or transpose numbers, for example, 63 for 36 or 785 for 875.

- They may need help to read a digital and analog clock.

- They may have difficulty with time management, be unable to recall schedules and sequences of past or future events, be unable to keep track of time and be chronically late. They may be unable to memorize sequences of historical facts and dates; historical timelines may be vague.

- Children with dyscalculia may have difficulty remembering the rules for playing sporting games, remembering the order of play, and understanding technicalities. They are quickly “lost” when observing fast-action games like football, baseball, and basketball. As a result, they may avoid physical activities and physical games.

- People with dyscalculia may be unable to grasp and remember mathematical concepts, rules, formulae, and sequences.

- They may be unable to conceptualize and execute math processes (they can do the correct computation but do not understand why a strategy worked, so they can not transfer knowledge to new problems).

- Extreme cases of dyscalculia may lead to a phobia of mathematics and mathematical devices.

Finger-counting per se is not a sign of dyscalculia but rather a standard aid to memorizing math facts and learning efficient calculating strategies. However, persistent finger-counting, particularly for frequently repeated, easy-calculating tasks, indicates a problem with calculation.

Dyscalculia symptoms and signs by age

Toddlers and preschoolers

- Difficulty learning to count

- Difficulty sorting

- Difficulty corresponding numbers to objects

- Difficulty with auditory memory of numbers

.

Kindergarten

- Difficulty counting

- Difficulty subitizing

- Trouble with number recognition

.

Early elementary

- Difficulty with magnitude comparison

- Trouble learning math facts

- Difficulty with math problem-solving skills

- Over-reliance on finger counting for more than basic sums

- Anxiety during math tasks

.

Late elementary through middle

- Difficulties with precision during math work

- Difficulty remembering previously encountered patterns

- Difficulty sequencing multiple steps of math problems

- Difficulty understanding real-world representations of math formulae

- Anxiety during math tasks

.

High school

- Struggle to apply math concepts to everyday life, including money matters, estimating speed and distance

- Trouble with measurements

- Difficulty grasping information from graphs or charts

- Difficulty arriving at different approaches to the same math problem

- Anxiety during math tasks

.

Edublox offers live online tutoring to students with dyscalculia. Our students are in the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s math learning needs.

.

Key takeaways

Delve deeper

Dyscalculia statistics

There is no general agreement on the precise meaning of the term dyscalculia. Therefore, reports of dyscalculia’s prevalence vary depending on the definition and situation. Research suggests it has the same prevalence as dyslexia (about 6–8% of children), although it is far less widely recognized by parents and educators.

Dyscalculia types and subtypes

The term developmental dyscalculia is used to distinguish the problem in children and youth from similar problems experienced by adults after severe head injuries or as a result of a stroke. This type of dyscalculia is known as acquired dyscalculia. There are other types and several subtypes.

What causes dyscalculia?

Most problems can only be solved if one knows what causes that particular problem. A viable point of departure would thus be to ask: what causes dyscalculia? We investigate genetic influences, cognitive deficits, mathematical skills, and brain differences.

Dyscalculia treatment and intervention

We discuss the most important strategies that need to be applied to help a student overcome a math learning disability. We also look at the Edublox program that offers online help to students with mild to severe dyscalculia.

Authored by Susan du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities.

Medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).

.

Bibliography:

Hornigold, J. (2015). Dyscalculia pocketbook. Alresford, Hampshire: Teachers’ Pocketbooks.

Peard, R. (2010). Dyscalculia: What is its prevalence? Research evidence from case studies. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 8, 106–113.

Soares, N., Evans, T., & Patel, D. R. (2018). Specific learning disability in mathematics: A comprehensive review. Translational Pediatrics, 7(1), 48–62.

Sousa, D. A. (2015). How the brain learns mathematics, 2nd ed. California: Corwin Press.