Dyslexia is often used to describe persistent and severe reading difficulties. Over the years, the term has been defined in various—and sometimes conflicting—ways. This lack of consensus has led many educators to avoid using it altogether, opting instead for broader terms like reading disability or learning disability.

According to the International Literacy Association (2016), “There is no empirical basis for using the term dyslexia to distinguish a group of children who are different from others experiencing difficulty in acquiring literacy.” In this view, dyslexia represents students at the lower end of the reading continuum—without implying a distinct neurological category.

While the debate continues, one thing is clear: reading difficulties are real, complex, and in need of effective intervention. Here are some important facts about dyslexia.

1.) James Hinshelwood named it “congenital word-blindness” (1907)

In the early 1900s, Scottish ophthalmologist James Hinshelwood described children with typical intelligence who had unexpected difficulty learning to read. He called the condition congenital word-blindness, believing it to be a brain-based disorder. Hinshelwood emphasized early intervention, noting that the brain was most responsive to instruction during childhood. He also believed in neuroplasticity long before the term became mainstream, suggesting that retraining the opposite hemisphere could compensate for lost function in cases of acquired dyslexia.

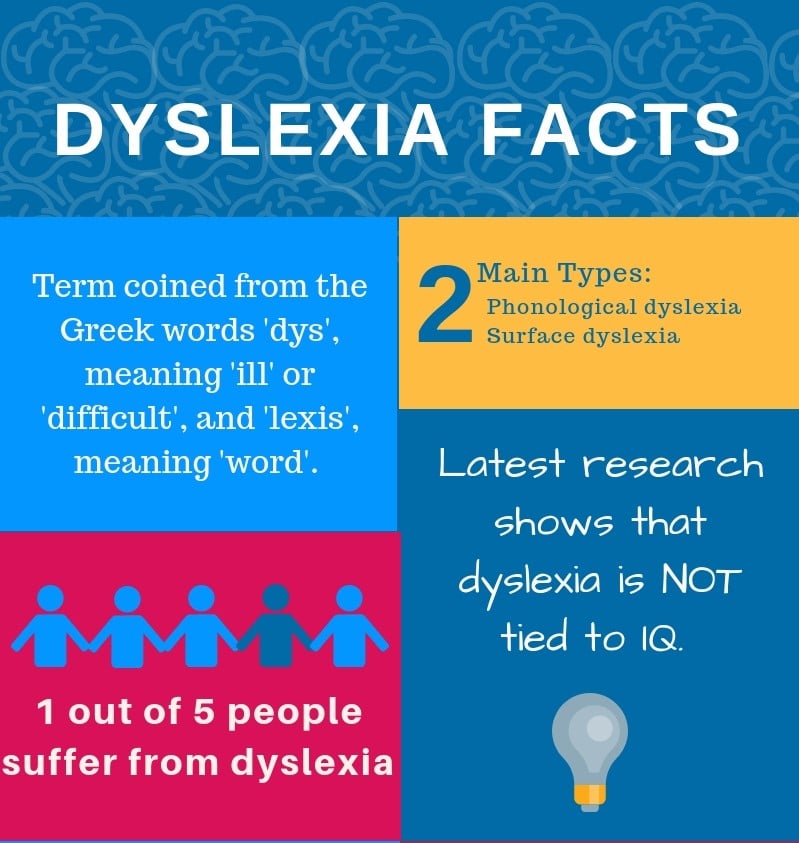

2.) The word “dyslexia” comes from Greek and was coined in 1884

The term dyslexia was introduced by German ophthalmologist Rudolf Berlin in 1884. He combined the Greek words dys (meaning “difficulty”) and lexis (“word” or “language”) to describe patients who lost the ability to read due to brain injury despite normal speech and intelligence. While Berlin used the term for what we now call acquired dyslexia, later researchers broadened it to include developmental dyslexia—reading difficulties that appear without brain injury and typically emerge in childhood.

3.) Dyslexia symptoms vary—but all involve difficulty with reading and spelling

Dyslexia is defined by persistent difficulty with accurate and/or fluent word reading and poor spelling. While individual symptoms may differ, common signs include:

- Difficulty decoding unfamiliar words

- Slow, effortful reading

- Trouble blending sounds into words (e.g., sounding out c-a-t but saying “cold”)

- Letter reversals (e.g., confusing b and d)

- Reordering letters (e.g., reading felt as left)

- Skipping letters or syllables (e.g., reading cat for cart)

- Inconsistent recognition of common sight words

- Spelling errors that don’t follow typical phonetic patterns

4.) Dyslexia affects up to 20% of the population

Research from Yale University and other sources estimates that dyslexia affects approximately 1 in 5 individuals. It is considered the most common learning difficulty, accounting for 80–90% of all learning disability diagnoses. While prevalence estimates vary depending on how dyslexia is defined, it is widely acknowledged as a widespread condition.

5.) Dyslexia tends to run in families

Genetics plays a significant role in dyslexia. If a parent has dyslexia, their child has a 40–60% chance of also struggling with reading. Studies have shown that first-degree relatives often show similar deficits in phonological processing (a core factor in dyslexia), word decoding, and spelling—even if they were never formally diagnosed. Brain imaging also shows familial patterns in how reading circuits function (Molfese et al., 2008).

6.) Dyslexia varies in severity

Dyslexia can be mild, moderate, or severe.

- Mild dyslexia may cause occasional reading or spelling problems but often goes undetected, especially in bright or motivated students.

- Moderate dyslexia leads to ongoing struggles with reading fluency, spelling, and written expression, often requiring targeted support.

- Severe dyslexia can make reading and writing extremely difficult, with schoolwork taking much longer and requiring consistent assistance.

7.) Deficits in phonological processing are a core factor

Many people with dyslexia struggle with phonological processing—the ability to recognize and manipulate the sounds of spoken language. A key component is phonemic awareness, which involves identifying and working with individual word sounds. Children with poor phonemic awareness may have difficulty rhyming, blending sounds, or segmenting words into sounds (e.g., saying the individual sounds in cat as /k/ /a/ /t/). These foundational weaknesses make decoding and spelling difficult, even with strong intelligence and oral language.

8.) Dyslexia is linked to slow processing speed

Processing speed refers to how quickly someone can take in, understand, and respond to information. In a Norwegian study, participants with dyslexia took part in simulated driving tests while reacting to road signs. Compared to controls, they were 20% slower on rural roads and 30% slower in city settings. This slower processing does not just affect driving—it can impact how quickly dyslexic individuals recognize letters, decode words, and follow spoken instructions.

9.) Dyslexics often have deficits in auditory working memory

Auditory working memory is the ability to hold and manipulate sounds in mind—like remembering a phone number long enough to write it down or following multi-step spoken instructions. In a 2014 study, Weiss and colleagues tested dyslexic and nondyslexic musicians on auditory perception and memory. While they performed similarly on listening tasks, the dyslexic group did significantly worse on memory tasks involving rhythm, melody, and speech sounds, and these working memory deficits were strongly associated with lower reading accuracy.

10.) Many people with dyslexia struggle with sequencing

Sequencing is the ability to perceive, remember, and reproduce information in order. Research has shown that children with dyslexia often perform worse than their peers on visual and auditory sequential memory tasks. One study in the Journal of General Psychology found dyslexic children were significantly less accurate than controls in sequencing tasks. Another, published in the Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, found auditory sequential memory impairments in both visually- and auditorily-based dyslexic readers, compared to good readers.

11.) Many people with dyslexia have poor long-term memory

Long-term memory stores information over time—from sounds to vocabulary and spelling rules. A study published in Dyslexia compared 60 dyslexic children to 65 typically developing peers. The dyslexic group showed generalized impairments in long-term memory, including verbal, visual-spatial, and visual-object memory.

12.) Dyslexia is often caused by multiple interacting deficits

The phonological deficit theory remains the most established explanation for dyslexia. It proposes that difficulties in representing, storing, and retrieving speech sounds underlie many reading problems. Research from the UK’s York group and others has strongly supported the role of phonological skills in early reading development (Fawcett, 2001). However, newer studies suggest phonological issues alone may not explain all cases. Instead, multiple interacting deficits are now seen as more accurate predictors of reading disability (Pennington, 2006; Peterson & Pennington, 2012; van Bergen et al., 2014).

Menghini et al. (2010b) found that only 18.3% of children with dyslexia had a phonological deficit alone. The rest showed additional challenges, including:

- 16.6% with executive function deficits

- 13.3% with visual-spatial, attention, and executive deficits

- 8.3% with attention and perceptual deficits

- 8.3% with attention and executive deficits

Likewise, Moura et al. (2015) identified deficits in processing speed, cognitive flexibility, and verbal fluency in dyslexic children compared to typically developing peers.

13.) There are two main types of dyslexia

Reading difficulties related to visual-processing weaknesses have been called surface dyslexia, dyseidetic dyslexia, and orthographic dyslexia. Reading delays associated with phonological processing difficulties are referred to as phonological dyslexia and dysphonetic dyslexia.

14.) Dyslexia is not tied to IQ

Dyslexia was once defined as a gap between reading ability and intelligence, but this model no longer holds. Brain imaging studies by Tanaka et al. (2011) found no differences in brain activity between poor readers with dyslexia and those with low IQs. All poor readers showed less activation in key reading areas compared to typical readers, regardless of their intelligence level. This confirms that dyslexia can affect students across the IQ spectrum.

15.) The dyslexic’s brain differs from the typical reader’s brain

In a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of dyslexia, Martin et al. (2016) list studies in which differences between groups with and without dyslexia were found in specific brain regions. The most consistent findings concerned the left occipitotemporal cortex, which includes the visual word form area (VWFA), thought critical for reading (shown in yellow). The left inferior parietal lobule came in a close second in the meta-analysis study by Martin and colleagues (shown in red). This part of the brain is involved in word analysis, grapheme-to-phoneme conversion, and general phonological and semantic processing.

Imaging also reveals compensatory overactivation in other parts of the reading system (shown in green). The compensatory neural systems allow a dyslexic person to read more accurately. However, the critical visual word-form area remains disrupted, and difficulties with rapid, fluent, automatic reading persist. As a result, the person with dyslexia continues to read slowly (Shaywitz, 2003).

16.) Brain differences might be a consequence and not the cause

These brain differences are often viewed as the cause of dyslexia. However, studies suggest that the cause-effect relationship is reversed. In other words, these brain differences are not the cause of reading difficulties but the result.

In one study published online in the Journal of Neuroscience, researchers analyzed the brains of children with dyslexia. They compared them with two other groups of children: an age-matched group without dyslexia and a group of younger children with the same reading level as those with dyslexia. Although the children with dyslexia had less gray matter than age-matched children without dyslexia, they had the same amount of gray matter as the younger children at the same reading level. Krafnick et al. (2014) suggest that the anatomical differences reported in left-hemisphere language-processing regions of the brain appear to be a consequence of reading experience as opposed to a cause of dyslexia.

17.) Neuroplasticity offers hope to people with dyslexia

Advances in technology have made it possible for scientists to see inside the brain, resulting in the knowledge that the brain is ‘plastic.’ Neuroplasticity is the ability of the brain to develop new neurons and synapses in response to learning.

Positive correlations between gray matter and the time spent learning and practicing their specialization have been reported in several groups, including musicians, jugglers, and bilinguals (Maguire et al., 2006). A study by Skeide and colleagues shows that when adults learn to read for the first time, the changes that occur in their brain are not limited to the outer layer of the brain, the cortex, but extend to deep brain structures in the thalamus and the brainstem. This was observed in illiterate Indian women who learned how to read and write for six months.

18.) Start intervention early to prevent academic and emotional problems

Reading difficulties in childhood can cast a long shadow. Research shows that reading ability is closely linked to a child’s academic performance, self-esteem, and emotional well-being. Children who struggle to read often fall behind in school, feel demoralized and may disengage from learning altogether.

Over time, poor literacy is associated with higher dropout rates and long-term social consequences. In the United States, up to 75% of incarcerated individuals have not finished high school, and around 70% are functionally illiterate, reading below a fourth-grade level. Many underemployed and unemployed adults were once children who never mastered the reading skills needed for success.

19.) Accommodations are not the same thing as intervention

Once a child has a dyslexia diagnosis, they may be eligible for accommodations, such as extended time on tests. While accommodations might improve grades, they are not a replacement for intervention. Accommodations will not teach a child to read or spell.

20.) Your child can make it!

A few wrong turns do not define a child’s future. With the right support and intervention, children with dyslexia can thrive —in school and life. People with dyslexia succeed every day in nearly every field you can imagine—from science and medicine to business, the arts, and technology. Dyslexia may shape the journey, but it does not limit the destination.

At Edublox, we believe that every child can succeed — and with the right support, they do. Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyslexia across the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond. Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs and how we can help them thrive.

.

References and sources for 20 Facts About Dyslexia:

- Byrne, B. (2011). Evaluating the role of phonological factors in early literacy development: Insights from experimental and behavior-genetic studies. In S. A. Brady, D. Braze, & C. A. Fowler (Eds.), Explaining individual differences in reading: Theory and evidence (pp. 175-195). New York: Psychology Press.

- Dunson, W. E. (2013). School success for kids with dyslexia & other reading disabilities. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press Inc.

- Elliott, J. G., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2014). The dyslexia debate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fawcett, A. (2001). Dyslexia at school: A review of research for the DfES. (Unpublished review for the Department for Education and Skills, the British Dyslexia Association and the Dyslexia Institute).

- Fern-Pollak, L., & Masterson, J. (2016). Dyslexia and the English writing system. In V. Cook & D. Ryan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of the English language (pp. 223-234). New York: Routledge.

- Gentry, J. R. (2006). Breaking the code: The new science of beginning reading and writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Hinshelwood, J. (1917). Congenital word-blindness. London: Lewis.

- Howes, N. L., Bigler, E. D., Lawson, J. S., & Burlingame, G. M. (1999). Reading disability subtypes and the test of memory and learning. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 14(3), 317–339.

- Krafnick, A. J., Flowers, D. L., Luetje, M. M., Napoliello, E. M., & Eden, G. F. (2014). An investigation into the origin of anatomical differences in dyslexia. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(3), 901-908.

- Lyon, R. (2001). Measuring success: Using assessments and accountability to raise student achievement. Retrieved April 22, 2025, from ProjectPro website: http://projectpro.com/ICR/Research/Releases/NICHD_Testimony1.htm

- Maguire, E. A., Woollett, K., & Spiers, H. J. (2006). London taxi drivers and bus drivers: A structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis. Hippocampus, 16(12), 1091-1101.

- Martin, A., Kronbichler, M., & Richlan, F. (2016). Dyslexic brain activation abnormalities in deep and shallow orthographies: A meta-analysis of 28 functional neuroimaging studies. Human Brain Mapping, 37, 2676–2699.

- Mather, N., & Wendling, B. J. (2012). Essentials of dyslexia assessment and intervention. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Menghini, D., Carlesimo G. A., Marotta, L., Finzi, A., & Vicari, S. (2010a). Developmental dyslexia and explicit long-term memory. Dyslexia, 16(3), 213-225.

- Menghini, D., Finzi, A., Benassi, M., Bolzani, R., Facoetti, A., Giovagnoli, S., … Vicari, S. (2010b). Different underlying neurocognitive deficits in developmental dyslexia: A comparative study. Neuropsychologia, 48(4), 863–72.

- Molfese, D. L., Molfese, V. J., Barnes, M. E., Warren, C. G., & Molfese, P. J. (2008). Familial predictors of dyslexia: Evidence from preschool children with and without familial dyslexia risk. In G. Reid, A. J. Fawcett, F. Manis, & L. Siegel (Eds.). The SAGE handbook of dyslexia (pp. 99-120). London: Sage.

- Moura, O., Simões, M. R., & Pereira, M. (2015). Executive functioning in children with developmental dyslexia. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 28(S1), 20-41.

- Pais, A. (1982). Subtle is the lord: The science and the life of Albert Einstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pennington, B. F. (2006). From single to multiple deficit models of developmental disorders. Cognition, 101(2), 385-413.

- Peterson, R. L., & Pennington, B. F. (2012). Developmental dyslexia. The Lancet, 379, 1997–2007.

- Shaywitz, S. (2003). Overcoming dyslexia. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Sigmundsson, H. (2005). Do visual processing deficits cause problem on response time task for dyslexics? Brain and Cognition, 58(2), 213–216.

- Skeide, M. A., Kumar, M., Mishra, R. K., Tripathi, V. N., Guleria, A., Singh, J .P., … Huettig, F. (2017). Learning to read alters cortico-subcortical cross-talk in the visual system of illiterates. Science Advances, 3(5), e1602612.

- Stanley, G., Kaplan, I., & Poole, C. (1975). Cognitive and nonverbal perceptual processing in dyslexics. Journal of General Psychology, 93(1), 67-72.

- Tanaka, H., Black, J. M., Hulme, C., Stanley, L. M., Kesler, S. R., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., … Hoeft, F. (2011). The brain basis of the phonological deficit in dyslexia is independent of IQ. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1442-1451.

- Van Bergen, E., van der Leij, A., & de Jong, P. F. (2014). The intergenerational multiple deficit model and the case of dyslexia. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8(346), 1-13.

- Weiss, A. H., Granot, R. Y., & Ahissar, M. (2014). The enigma of dyslexic musicians. Neuropsychologia, 54, 28-40.

20 Facts About Dyslexia was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyslexia specialist with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities.

Edublox is proud to be a member of the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), a leading organization dedicated to evidence-based research and advocacy for individuals with dyslexia and related learning difficulties.