Dysgraphia is a neurological learning disability that disrupts the complex process of writing. It can affect spelling, handwriting, and the ability to organize and express thoughts on paper. While some struggle mainly with fine motor control, others find that forming sentences, structuring ideas, or remembering correct spelling is the greater challenge. These difficulties can make written tasks slow, frustrating, and exhausting, impacting both academic performance and self-confidence..

Table of contents:

- Overview

- What is dysgraphia?

- Dysgraphia symptoms and signs

- Different types of dysgraphia

- Dysgraphia and comorbidity

- What causes developmental dysgraphia?

- Dysgraphia treatment

- Key takeaways

Overview

Writing is not only a fundamental academic skill but also a key means of communication, self-expression, and learning across all subjects. It is closely tied to overall academic achievement, with research showing that on average, writing-related tasks can occupy up to half of a typical school day (Amundson & Weil, 1996).

For most students, writing develops through exposure to instruction, practice, and feedback. However, some children continue to struggle with writing despite having received adequate teaching. These persistent difficulties may be an indication of dysgraphia — a term often used interchangeably with “specific learning disorder in written expression.” Both describe individuals whose writing ability is significantly below what would be expected for their age and cognitive level (Cahill, 2009).

Dysgraphia can affect handwriting, spelling, and the ability to translate thoughts into written language. The impact can extend beyond the mechanics of forming letters to influence sentence structure, organization of ideas, and overall written communication. For students with dysgraphia, the classroom experience is often marked by frustration, slower work pace, and a constant struggle to keep up with peers, particularly when written output is required.

While dysgraphia is sometimes narrowly defined as a handwriting disorder, in practice, it often involves a complex interplay of language, cognitive, and motor skills. Understanding this broader perspective is essential for accurate identification and effective intervention.

What is dysgraphia?

The term dysgraphia comes from the Greek dys, meaning “ill” or “difficult,” and graphein, meaning “to write.” It describes a persistent difficulty with written expression that cannot be explained by lack of instruction, low intelligence, or other external factors.

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), dysgraphia is not listed as a separate diagnosis. Instead, it falls under the broader category of Specific Learning Disorder with impairment in written expression. This classification reflects the reality that writing is a complex skill, supported by multiple systems in the brain, and that difficulties can manifest in different ways.

At its broadest, dysgraphia refers to problems at any stage of the writing process — from the mechanics of handwriting to the higher-level skills of spelling, sentence construction, and idea organization. This includes:

- Poor letter formation and legibility

- Inconsistent spacing and alignment on the page

- Frequent spelling errors and difficulty applying spelling rules

- Slow writing speed and difficulty keeping up with written assignments

- Weaknesses in grammar, punctuation, and overall composition

Some researchers and clinicians use the term more narrowly, limiting it to handwriting difficulties alone. However, in this article, we use the broader definition, recognizing that writing challenges can affect handwriting, spelling, and written composition — sometimes one area in isolation, but often in combination.

Children with dysgraphia may produce work that is far below their intellectual ability, creating a gap between what they can say aloud and what they can express on paper. This mismatch can cause frustration, lower self-esteem, and reduced participation in academic tasks, especially as written work demands increase with age.

How common is dysgraphia?

Determining how common dysgraphia is remains challenging because there is no universally accepted definition and limited research devoted solely to the disorder. In many studies, dysgraphia is grouped under broader categories of writing difficulties or specific learning disorders, which makes direct comparisons difficult.

Even so, available evidence suggests that writing challenges are far from rare. Kushki et al. (2011) estimate that between 10% and 30% of children experience significant difficulty with writing. The exact figure depends heavily on the criteria used to define dysgraphia, the population being studied, and whether the focus is on handwriting, spelling, or composition.

Writing difficulties are especially prevalent in children who already have other learning or attention-related conditions. For example, research by Adi-Japha et al. (2007) found that children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) frequently demonstrate weaknesses in writing skills, even if their reading ability is within the normal range. These writing difficulties often persist despite standard classroom instruction.

Because writing is a foundational academic skill, the persistence of dysgraphia can have long-term effects on a child’s educational experience. Struggles with handwriting and written expression can slow work production, reduce classroom participation, and affect performance across multiple subjects. This makes early identification and targeted intervention essential.

Dysgraphia symptoms and signs

Signs and symptoms of dysgraphia can appear in handwriting, spelling, and written composition. A child may show difficulties in just one area or in all three.

Handwriting

- Illegible writing despite adequate time and instruction.

- Mixing print and cursive within the same word or sentence.

- Inconsistent use of upper- and lowercase letters.

- Irregular letter size, shape, or slant.

- Poor alignment on the page; difficulty keeping writing on the line or within margins.

- Uneven spacing between words and letters.

- Awkward pencil grip, such as holding the writing instrument too close to the tip or wrapping the thumb over two fingers.

- Writing with the face very close to the paper.

- Trouble remembering motor patterns for letters.

- Talking aloud while writing or closely watching the writing hand.

- Slow, labored copying or writing, even when neat.

Spelling

- Inconsistent spelling of the same word within the same passage.

- Letter reversals, substitutions, omissions, or incorrect suffixes.

- Poor understanding of spelling rules and patterns.

- Lack of phonemic awareness (more common in younger children).

- Missing or random punctuation.

Written composition

- Strong oral skills but weaker writing skills.

- Simplistic writing or overly complex sentences with syntax, morphology, or semantics errors.

- Limited vocabulary in written work.

- Difficulty generating ideas, brainstorming, or researching.

- Problems organizing thoughts and sequencing information.

- Not knowing how to start a writing task.

Warning signs by age

Early writers (preschool–1st grade)

- Tight, awkward pencil grip and body posture.

- Avoidance of writing or drawing tasks.

- Trouble forming letter shapes.

- Inconsistent spacing between letters and words.

- Poor understanding of uppercase vs lowercase letters.

- Inability to write or draw on the line or within margins.

- Fatigue or loss of interest after short writing tasks.

Young students (2nd–5th grade)

- Illegible handwriting.

- Mixing print and cursive.

- Saying words aloud while writing.

- Losing focus on meaning because of the handwriting effort.

- Trouble thinking of words to write.

- Omitting or leaving words unfinished.

Teenagers and adults

- Trouble organizing thoughts on paper.

- Difficulty keeping track of ideas already written.

- Weaknesses in grammar, sentence structure, and syntax.

- There is a large gap between verbal ability and written work.

Different types of dysgraphia

Dysgraphia can be classified in different ways, but researchers generally distinguish between acquired dysgraphia and developmental dysgraphia.

- Acquired dysgraphia occurs after an individual has already learned to write, typically due to brain injury, illness, or a degenerative condition.

- Developmental dysgraphia appears in childhood and involves difficulty learning to write despite normal instruction. Within developmental dysgraphia, three main subtypes are often described:.

| Motor Dysgraphia | Spatial Dysgraphia | Dyslexic Dysgraphia |

|---|---|---|

| Caused by poor fine motor skills, weak muscle tone, or motor clumsiness. Writing is often slow, effortful, and illegible even when copying. Letter formation may be neat only in short bursts but cannot be sustained. Spelling skills are usually intact. Finger-tapping speed (fine motor test) is below average. | Caused by difficulties in understanding spatial relationships. Both spontaneous and copied writing are often illegible. Spelling is generally normal, and fine motor speed is unaffected. Students struggle to keep writing on the lines and to space words evenly. | Linked to language processing issues more than motor control. Spontaneous writing is illegible and spelling is poor, but copied work is relatively neat. Finger-tapping speed is normal. Dyslexia is not always present, but the two often co-occur. |

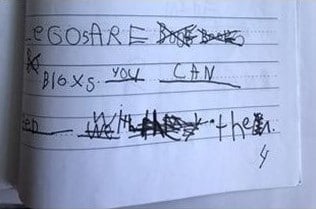

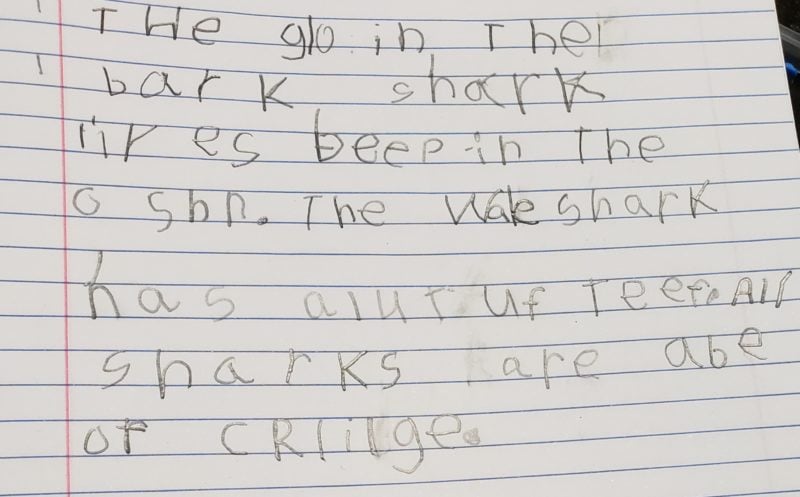

Below is the writing of an eight-year-old German boy with spatial dysgraphia before and after three months of Edublox training:

Dysgraphia and comorbidity

Dysgraphia rarely exists in isolation. It often co-occurs with other learning and developmental disorders, which can make diagnosis and intervention more complex. Understanding these overlaps is important, as the presence of multiple conditions may require a broader and more individualized support plan.

| Condition | Key Overlap with Dysgraphia | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dyslexia | Both can involve difficulties with letter formation, sequencing, and spelling. Mild clumsiness — a possible sign of dysgraphia — is sometimes observed in dyslexia. | In the British Births cohort (Haslum, 1989), deficits in certain motor tasks, such as catching a ball after clapping or walking backward in a straight line, were associated with dyslexia. These motor challenges are also seen in dysgraphia. |

| Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD / Dyspraxia) | Both may affect fine motor coordination needed for handwriting. | While DCD primarily impacts motor skills, it can lead to handwriting challenges similar to those seen in motor dysgraphia. However, the underlying causes differ. |

| ADHD | Students with ADHD often have graphomotor weaknesses, slower writing, and higher rates of spelling errors. | One study found that 59% of students with ADHD also had dysgraphia, and 92% of the 59% had weaknesses in graphomotor skills (Adi-Japha et al., 2007). Spelling errors often show a unique “graphemic buffer” pattern linked to attention deficits. |

What causes developmental dysgraphia?

Developmental dysgraphia does not have a single cause. Instead, it arises from a combination of neurological, genetic, and cognitive and motor factors that affect the complex process of writing. Understanding these different layers is important for both diagnosis and intervention.

Neurological factors

Writing depends on the smooth interaction of brain regions responsible for motor control, language, and spatial organization. Neuroimaging and lesion studies have identified several key areas:

- Left premotor cortex – Retrieves the stored “motor image” of letters and translates it into motor plans for writing (Tohgi et al., 1995).

- Parietal lobes – Support spatial awareness and the arrangement of letters and words on the page.

- Cerebellum – Regulates fine motor control, timing, and coordination, while also contributing to aspects of language processing. Cerebellar differences have been observed in both dysgraphia and dyslexia (Roeltgen, 2000; Docking et al., 2003; Katanoda et al., 2001).

Disruption in any of these areas can interfere with the integration of motor and linguistic processes. This may lead to weaknesses in the graphemic buffer (short-term storage of letter patterns), allographic conversion (choosing correct letter forms), or the motor execution of handwriting (Ellis, 1982; Zesiger et al., 1997).

Genetic factors

Although research specific to dysgraphia genetics is limited, there is growing evidence for heritable influences:

- Shared genetic origins – Stevenson et al. (1993) found overlap in the genetic factors linked to ADHD and spelling disability, suggesting that the same genetic vulnerabilities may contribute to dysgraphia.

- Language and motor-related genes – Genes associated with dyslexia and speech/language disorders (DYX1C1, ROBO1, FOXP2) influence neuronal migration, axonal guidance, and brain connectivity — processes that may also affect writing skills.

- Family patterns – Clinical observations frequently show a higher incidence of handwriting and spelling difficulties among relatives, pointing toward inherited risk.

Weak writing prerequisites

Human learning is a layered process — certain skills must be mastered before more advanced abilities can develop. Just as a child must learn to count before understanding addition, there are foundational skills that support writing. If these are weak, progress in writing will be slow or inconsistent, regardless of how much practice a child gets.

Research confirms that writing relies on language, cognitive, and motor skills working together:

- Language – Knowing letter sounds, understanding vocabulary and grammar, and being able to describe ideas all influence writing quality.

- Attention – Writing requires sustained focus over long periods and constant monitoring of what has been written.

- Ordering – Some children struggle with sequential ordering (keeping letters, words, and ideas in the correct order) or spatial ordering (arranging text properly on a page).

- Memory – Studies show that certain forms of dysgraphia are associated with visual memory problems, which can be more disruptive than visuomotor weaknesses (Vlachos & Karapetsas, 2003).

- Graphomotor skills – Fine motor coordination and the ability to form letters fluently are essential for keeping pace with ideas during writing. Weaknesses here can result in slow, effortful handwriting.

Dysgraphia treatment

Diagnosis of dysgraphia

A diagnosis of dysgraphia can only be made after a comprehensive evaluation by a qualified professional, such as an educational psychologist or occupational therapist. The process typically includes:

- Educational history – Reviewing past school performance, teacher reports, and prior interventions.

- Writing samples – Assessing handwriting legibility, speed, letter formation, spacing, spelling, and organization of written work.

- Cognitive testing – Measuring memory, attention, sequencing, and other processing skills that underlie writing.

- Motor and visual–motor assessments – Evaluating fine motor control, grip, and coordination between vision and hand movements.

- Language skills – Testing vocabulary, grammar, and sentence construction.

The goal is to identify both the visible symptoms (e.g., poor handwriting) and underlying causes (e.g., weak visual memory or motor planning difficulties) so that intervention can be tailored to the learner’s needs.

Treatment for dysgraphia

Treatment for dysgraphia should be individualized, addressing the specific causes and challenges identified during diagnosis. In most cases, an effective plan combines skill-building, strategy training, and classroom accommodations.

1. Skill-building

- Fine motor and graphomotor exercises to improve hand strength, grip, and letter formation.

- Visual–motor integration activities, such as tracing patterns or copying shapes to coordinate vision and movement.

- Explicit spelling and handwriting instruction to build accuracy and fluency.

2. Writing strategies

- Teaching step-by-step planning and organization before writing.

- Using graphic organizers or templates to structure ideas.

- Encouraging short, frequent writing sessions to reduce fatigue.

3. Accommodations

- Allowing extra time for writing tasks.

- Offering assistive technology such as speech-to-text or keyboarding.

- Providing printed notes or outlines to minimize copying demands.

4. The Edublox approach

Edublox programs target both underlying cognitive skills (e.g., visual memory, sequencing, attention) and visible writing difficulties (e.g., handwriting, spelling, composition). Each program is customized, which is especially important when dysgraphia co-occurs with other learning difficulties.

Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs, or visit our website to learn more about how we can help.

Key takeaways

Authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years of experience in specific learning disabilities, and medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).

References:

- Adi-Japha, E., Landau, Y., Frenkel, L., Teicher, M., Gross-Tsur, V., & Shalev, R. (2007). ADHD and dysgraphia: Underlying mechanisms. Cortex, 43(6), 700–709.

- American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed. revised). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Amundson, S., & Weil, M. (1996). Prewriting and handwriting skills. In J. Case-Smith, A. Allen, & P. N. Pratt (Eds.), Occupational therapy for children (3rd ed., pp. 521-524). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

- Cahill, S. M. (2009). Where does handwriting fit in? Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(4), 223–228.

- Docking, K., Murdoch, B., & Ward, E. (2003). Cerebellar language and cognitive functions in childhood: A comparative review of the clinical research. Aphasiology, 17(12), 1153–1161.

- Ellis, A. W. (1982). Spelling and writing (and reading and speaking). In A. W. Ellis (Ed.), Normality and pathology in cognitive functions (pp. 113–146). London, England: Academic Press.

- Haslum, M. N. (1989). Predictors of dyslexia? The Irish Journal of Psychology, 10(4), 622–630.

- Katanoda, K., Yoshikawa, K., & Sugishita, M. (2001). A functional MRI study on the neural substrates for writing. Human Brain Mapping, 13(1), 34–42.

- Kushki, A., Schwellnus, H., Ilyas, F., & Chau, T. (2011). Changes in kinetics and kinematics of handwriting during a prolonged writing task in children with and without dysgraphia. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(3), 1058–1064.

- Roeltgen, D. P. (2000). Agraphia. In M. J. Farah & T. E. Feinberg (Eds.), Patient-based approaches to cognitive neuroscience (pp. 71–82). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Stevenson, J., Pennington, B. F., Gilger, J. W., DeFries, J. C., & Gillis, J. J. (1993). Hyperactivity and spelling disability: Testing for shared genetic aetiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(7), 1137–1152.

- Tohgi, H., Saitoh, K., Takahashi, S., Takahashi, H., Utsugisawa, K., Yonezawa, H., Hatano, K., & Sasaki, T. (1995). Agraphia and acalculia after a left prefrontal (F1, F2) infarction. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 58(5), 629–632.

- Vlachos, F., & Karapetsas, A. (2003). Visual memory deficit in children with dysgraphia. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 97, 1281–8.

- Zesiger, P., Martory, M.-D., & Mayer, E. (1997). Writing without graphic motor patterns: A case of dysgraphia for letters and digits sparing shorthand writing. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 14(5), 743–763.