Dysgraphia is a learning disability that affects a person’s ability to write. Dysgraphia is a neurological disorder characterized by difficulties with spelling, poor handwriting, and trouble putting thoughts on paper. People with dysgraphia may also struggle with fine motor skills and coordination, making writing assignments challenging.

.

Table of contents:

- Overview

- What is dysgraphia?

- Dysgraphia symptoms and signs

- Different types of dysgraphia

- Dysgraphia and comorbidity

- What causes developmental dysgraphia?

- Dysgraphia treatment

- Key takeaways

Overview

Writing is an essential academic skill linked to overall academic achievement (Cahill, 2009). On average, writing tasks occupy up to half of the school day (Amundson & Weil, 1996).

‘Dysgraphia’ and ‘specific learning disorder in written expression’ are terms used to describe those individuals who, despite exposure to adequate instruction, demonstrate writing ability discordant with their cognitive level and age.

What is dysgraphia?

The term dysgraphia is often used when discussing writing disabilities. The word was coined from the Greek words dys, ill or difficult, and graphein, to write. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) includes dysgraphia under the specific learning disorder category but does not define it as a separate disorder.

At its broadest definition, dysgraphia is a disorder of writing ability at any stage, including problems with letter formation and legibility, letter spacing, spelling, fine motor coordination, writing rate, grammar, and composition. Dysgraphia can also refer to severe handwriting difficulties only. We will use the first definition and look at its subcategories of spelling, handwriting, and written composition. Children with a writing disability may experience difficulties in one or more of these areas.

How common is dysgraphia?

Due to a lack of a clear-cut definition for dysgraphia and the dearth of research explicitly focused on it, there are few statistics regarding prevalence. However, writing disabilities are prevalent in students with learning disabilities, including in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Adi-Japha et al., 2007), and they tend to be persistent.

According to Kushki et al. (2011), 10 to 30% of children experience difficulty writing, although the exact prevalence depends on the definition of dysgraphia.

Dysgraphia symptoms and signs

Signs and symptoms associated with dysgraphia are many and varied.

What are the symptoms of dysgraphia?

Handwriting:

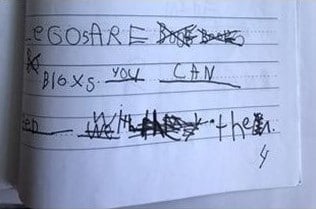

- Generally, writing is illegible despite the appropriate time and attention given to the task.

- Inconsistencies, which include mixtures of print and cursive and upper and lower case, or irregular sizes, shapes, or slants of letters.

- Inconsistent position on a page concerning lines and margins; uneven spaces between words and letters.

- Motor feedback difficulty: trouble tracking the location of the pencil; face too close to the paper; cramped or unusual grip, especially holding the writing instrument very close to the paper or holding the thumb over two fingers and writing from the wrists.

- Inability to remember motor patterns associated with letters.

- Inability to revisualize letters.

- Talking to themselves while writing or carefully watching the hand that is writing.

- Slow or labored copying or writing, even if neat and legible.

.

Spelling:

- Spelling errors: sometimes, the same word is spelled differently in the same sentence or paragraph.

- Reversals, phonic approximations, syllable omissions, and errors in common suffixes.

- Difficulty comprehending spelling rules, patterns, and structures (in older children) and lack of phonemic awareness (in younger children).

- Random or non-existent punctuation.

.

Written composition:

- Individuals with dysgraphia may exhibit strong verbal but inferior writing skills.

- Production problems: overly simplistic; too many common words or complex with syntax, morphology, or semantics errors.

- Unsophisticated ideation: difficulty selecting a topic, brainstorming, researching, thinking critically, coming up with ideas, et cetera.

- Organizational problems: they do not know where to begin and are confused with steps.

.

What are the warning signs of dysgraphia?

In early writers:

- Tight, awkward pencil grip and body position.

- Avoiding writing or drawing tasks.

- Trouble forming letter shapes.

- Inconsistent spacing between letters or words.

- Poor understanding of uppercase and lowercase letters.

- Inability to write or draw in a line or within margins.

- Quickly tiring while writing.

.

In young students:

- Illegible handwriting.

- A mixture of cursive and print writing.

- Saying words out loud while writing.

- Concentrating so hard on writing that comprehension of what was written is missed.

- Trouble thinking of words to write.

- Omitting or not finishing words in sentences.

.

In teenagers and adults:

- Trouble organizing thoughts on paper.

- Trouble keeping track of thoughts already written down.

- Difficulty with syntax structure and grammar.

- A large gap between written ideas and understanding demonstrated through speech.

Different types of dysgraphia

Dysgraphia is commonly thought of in the following two ways:

Acquired dysgraphia is associated with brain injury, disease, or degenerative conditions that cause the individual (typically an adult) to lose previously acquired skills in writing.

Developmental dysgraphia refers to difficulties in acquiring writing skills. This type of dysgraphia is typically considered in childhood. Researchers have identified several subtypes of developmental dysgraphia:

Motor dysgraphia

Motor dysgraphia is due to poor fine motor skills, dexterity and muscle tone, or unspecified motor clumsiness. Generally, written work is inferior to illegible, even if copied by sight from another document. Letter formation may be acceptable in very short writing samples, but this requires extreme effort, an unreasonable amount of time to accomplish, and cannot be sustained for a significant length of time. Writing is often slanted due to incorrect holding of a pen or pencil. Spelling skills are intact. Finger-tapping speed (a method for identifying fine motor problems) results are below average.

Spatial dysgraphia

Spatial dysgraphia is due to a defect in the understanding of space. This person has illegible spontaneously written work and illegible copied work but normal spelling and finger-tapping speed. Students with spatial dysgraphia often have trouble keeping their writing on the lines and difficulty with spacing between words.

Dyslexic dysgraphia

However, others have focused more on the language processing deficits related to written expression, with less emphasis on motor issues. Qualifying terms for this type of dysgraphia include “dysorthography,” “linguistic dysgraphia,” or “dyslexic dysgraphia.”

With dyslexic dysgraphia, a person’s spontaneously written work is illegible and their spelling poor, while copied work is pretty neat. Finger-tapping speed is normal. A dyslexic dysgraphic does not necessarily have dyslexia, but they often occur together.

Dysgraphia and comorbidity

Dysgraphia may also coexist with other learning disorders like dyslexia, further complicating a child’s academic journey.

Dyslexia and dysgraphia

Developmental dyslexia and dysgraphia are both learning differences. Dyslexia primarily affects reading. Dysgraphia mainly affects writing.

While dysgraphia and dyslexia are not the same conditions, there is an overlap between their symptoms. From the first studies of dyslexia, there has been continuing evidence that mild clumsiness — a possible symptom of dysgraphia — is associated with dyslexia.

Data from the British Births cohort examined the skills of 12,905 children. At age ten, they identified two motor skills tasks significantly associated with dyslexia: failure to throw a ball up, clap several times and catch it, and inability to walk backward in a straight line for six steps (Haslum, 1989). Deficits in motor skills are also symptomatic of dysgraphia.

Developmental Coordination Disorder

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), also known as dyspraxia, is a condition that affects a person’s ability to coordinate physical movements. This results in clumsiness and difficulty in acquiring motor skills to varying degrees.

DCD and dysgraphia can cause similar or overlapping struggles with writing. But they are different conditions.

Dysgraphia and ADHD

One study found that among students diagnosed with ADHD, 59% had dysgraphia, and 92% had weaknesses in graphomotor skills.

Adi-Japha et al. (2007) revealed that children with ADHD and normal reading skills made significantly more spelling errors than their non-ADHD counterparts. Furthermore, their spelling errors, such as letter insertions, substitutions, transpositions, and omissions, showed a unique pattern. This error type, also known as graphemic buffer errors, can be explained by impaired attention aspects needed for motor planning.

The results suggest that the spelling errors and writing deficits seen in children with ADHD stem primarily from non-linguistic deficits, while linguistic factors play a secondary role.

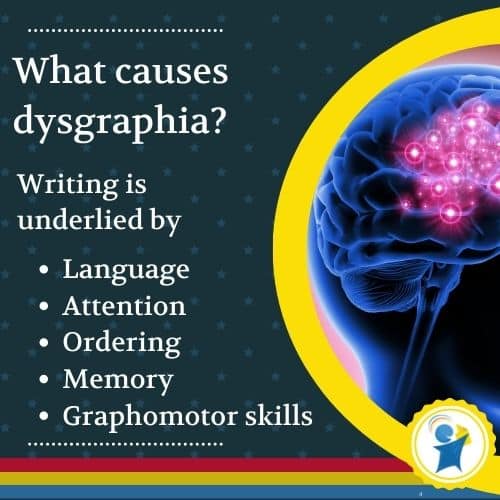

What causes developmental dysgraphia?

Human learning is a stratified process, which implies that specific skills must be mastered before it becomes possible to master subsequent skills. For example, one has to learn to count before it becomes possible to learn to add and subtract. In the same way, there are skills that a student must have mastered before they will be proficient in writing. The child’s writing will not improve until these underlying shortcomings have been addressed.

Research has confirmed that language, cognitive, and motor skills underlie writing.

Language

Language is an essential ingredient of writing. Recognizing letter sounds, comprehending words and their meanings, understanding word order and grammar to construct sentences, and describing or explaining ideas all affect a person’s effectiveness as a writer.

Attention

Writing often requires considerable mental energy and focus over long periods. Writers must preview what they want to convey and continually monitor what they have already written to stay on track.

Ordering

Many students with learning disorders have problems with ordering — either ordering things in time (temporal ordering), sequence (sequential ordering), or ordering things in physical space (spatial ordering).

Students with dysgraphia may struggle with spatial ordering, i.e., they have decreased awareness regarding the spatial arrangement of letters, words, or sentences on a page. They may also struggle with sequential ordering, i.e., difficulty placing in order or maintaining the order of letters, words, processes, or ideas.

Memory

A study by Vlachos and Karapetsas (2003) confirmed the claims of previous studies that at least some types of dysgraphia are associated with visual memory problems. Furthermore, their results suggest that children with dysgraphia suffer from poor visual memory even more than visuomotor skills. Visuomotor skills refer to vision and movement working together to produce actions.

Graphomotor skills

Graphomotor function refers to using muscles in the fingers and hands to form letters easily and legibly and to maintain a comfortable grip on a writing instrument. Children with graphomotor problems struggle with this, especially as assignment length increases. In addition, this function affects a student’s ability to keep pace with the flow of ideas.

Graphomotor skills include gross and fine motor skills. These two motor skills work together to provide coordination.

Dysgraphia treatment

How is dysgraphia diagnosed?

A diagnosis of dysgraphia can only be made after an extensive evaluation. Similar to the assessment process for dyslexia, an assessment for dysgraphia involves carefully considering the child’s learning strengths and weaknesses, their educational history, the extent of their spelling and expressive writing difficulties, and what impact intervention has had on their current academic achievement levels.

Edublox treatment for children with dysgraphia

Dysgraphia may be caused by language problems, weak underlying cognitive skills (e.g., poor visual memory), and deficient graphomotor skills (e.g., poor fine motor skills), which may affect handwriting, spelling, and writing composition. For this reason, each child’s Edublox program is tailor-made.

Since dysgraphia may co-occur with other learning disorders and problems, a customized approach is even more needed.

Book a free consultation to discuss your child’s learning needs, or visit our website for more information.

Key takeaways

Authored by Susan du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years of experience in specific learning disabilities.

Medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).

References:

Adi-Japha, E., Landau, Y., Frenkel, L., Teicher, M., Gross-Tsur, V., & Shalev, R. (2007). ADHD and dysgraphia: Underlying mechanisms. Cortex, 43(6): 700–9.

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed. revised). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Amundson, S., & Weil, M. (1996). Prewriting and handwriting skills. In J. Case-Smith, A. Allen, &

P. N. Pratt (Eds.), Occupational therapy for children (3rd ed., pp. 521-524). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Cahill, S. M. (2009). Where does handwriting fit in? Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(4): 223–228.

Haslum, M. N. (1989). Predictors of dyslexia? The Irish Journal of Psychology, 10(4): 622–30.

Kushki, A., Schwellnus, H., Ilyas, F., & Chau, T. (2011). Changes in kinetics and kinematics of handwriting during a prolonged writing task in children with and without dysgraphia. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(3): 1058–64.

Vlachos, F., & Karapetsas, A. (2003). Visual memory deficit in children with dysgraphia. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 97: 1281–8.