Table of contents:

- Overview

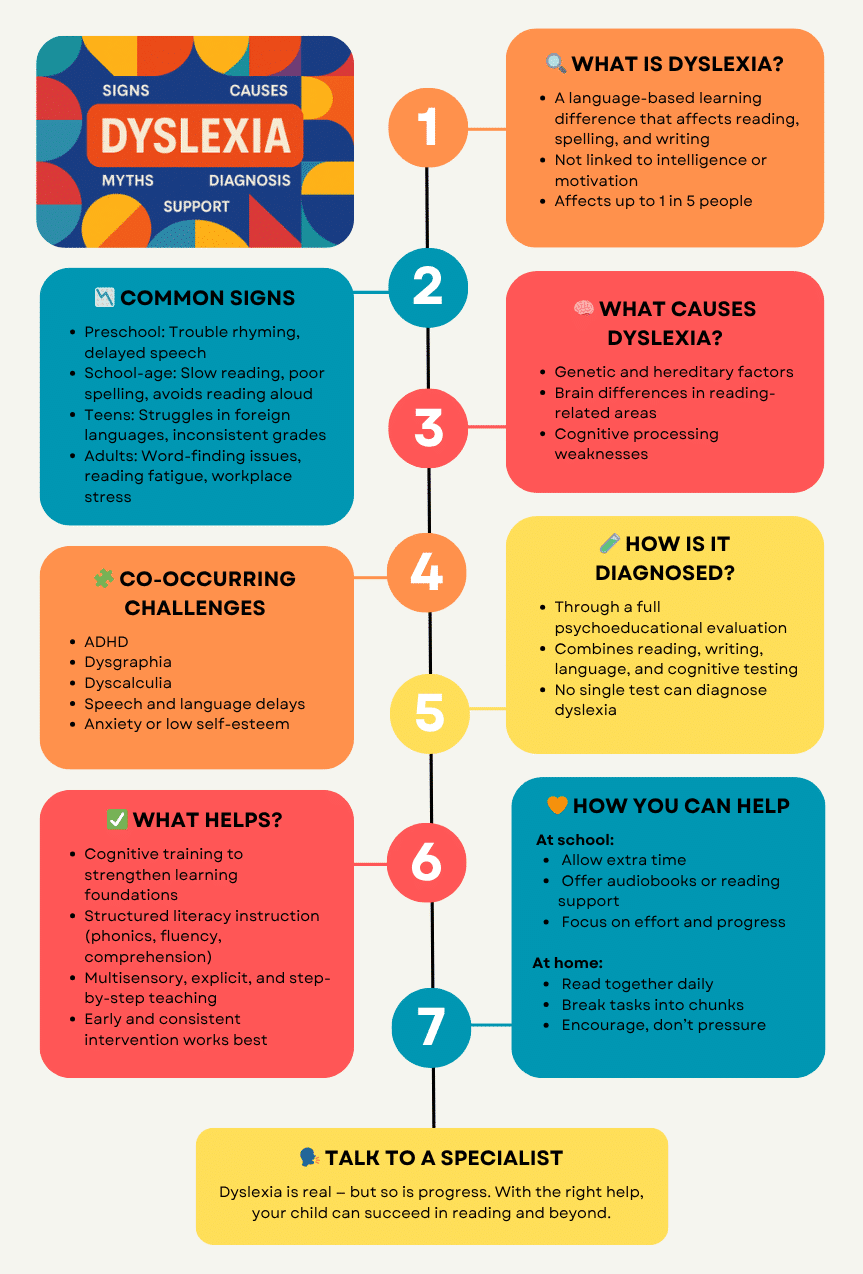

- Signs and symptoms

- Causes and risk factors

- Common myths

- Diagnosis and testing

- Intervention and prognosis

- Dyslexia in adults

- Supporting a child with dyslexia

- Key takeaways

- Talk to a specialist

.

1. Overview

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a specific learning disorder that affects the way the brain processes written and spoken language. It primarily interferes with reading, spelling, and writing, despite the individual having average or above-average intelligence, normal vision, and access to adequate educational opportunities.

At its core, dyslexia is not about laziness or lack of effort — it’s about the brain working differently when it comes to language. This difference makes it harder to connect letters to sounds (phonics), decode unfamiliar words, and read fluently. It can also impact spelling, written expression, memory for sequences, and even spoken language.

Dyslexia is not a disease and cannot be “cured,” but with the proper teaching methods and support, people with dyslexia can learn to read and write successfully.

Types of dyslexia

Researchers have identified several types of dyslexia, based on cause and pattern of symptoms. These types can overlap, and individuals often show a combination of traits.

- Developmental dyslexia: This type is present from early childhood and is believed to result from differences in brain development and genetics. It is the most common form and typically affects reading, spelling, and phonological processing.

- Acquired dyslexia: Also called alexia, this form occurs after brain injury or illness in someone who previously had normal reading abilities. It may result from stroke, trauma, or neurological disease.

- Phonological dyslexia: People with this type struggle to decode unfamiliar words by sounding them out. Phonemic awareness — the ability to break words into sounds — is often impaired.

- Surface dyslexia: Individuals with surface dyslexia read slowly and rely heavily on phonics, struggling to recognize common words by sight. This makes it challenging to read irregular words like “said” or “yacht.”

- Mixed dyslexia: Also known as double-deficit dyslexia, this type combines both phonological and surface dyslexia features. It is usually more severe and requires targeted intervention in both areas.

👉 👉 See our detailed guide on dyslexia types.

How common is dyslexia?

While only around 5-7% of the population is formally diagnosed with dyslexia, many experts estimate that up to 20% of people may exhibit symptoms that significantly impact reading and learning.

Dyslexia is the most common specific learning disability, accounting for approximately 80% of those diagnosed with learning disorders. Because it exists on a spectrum, its effects range from mild to severe — and many cases go undiagnosed, especially when students learn to compensate in other ways.

2. Signs and symptoms

The signs can vary depending on age and the severity of the condition. Here are some common signs in young children (typically ages 3–7) and students in elementary school to high school, though signs can vary by age and individual:

Preschool (ages 3–5 years)

- Delayed speech development compared to peers

- Difficulty learning and remembering the alphabet

- Trouble rhyming (e.g., cat/hat/mat)

- Mispronouncing words or mixing up sounds in words (e.g., “aminal” for “animal”)

- Difficulty learning the names of letters, colors, numbers, and shapes

- Trouble remembering sequences (like days of the week or songs)

- Struggles with fine motor skills (holding a pencil, using scissors)

- Difficulty recognizing their own name in print

Kindergarten to early elementary (ages 5–7 years)

- Difficulty learning letter sounds and matching them to letters

- Trouble sounding out simple words (like “cat” or “bat”)

- Avoids reading or gets frustrated with reading tasks

- Frequently guesses at words rather than sounding them out

- Confuses letters that look alike (b/d, p/q) or sounds that are similar

- Slow to learn new vocabulary words

- Trouble following multi-step directions

- Poor spelling or inconsistent spelling of the same word

- Has a hard time learning sight words (like “the,” “was,” “said”)

Elementary school to middle school

The signs usually become more noticeable and widespread, making school a challenge.

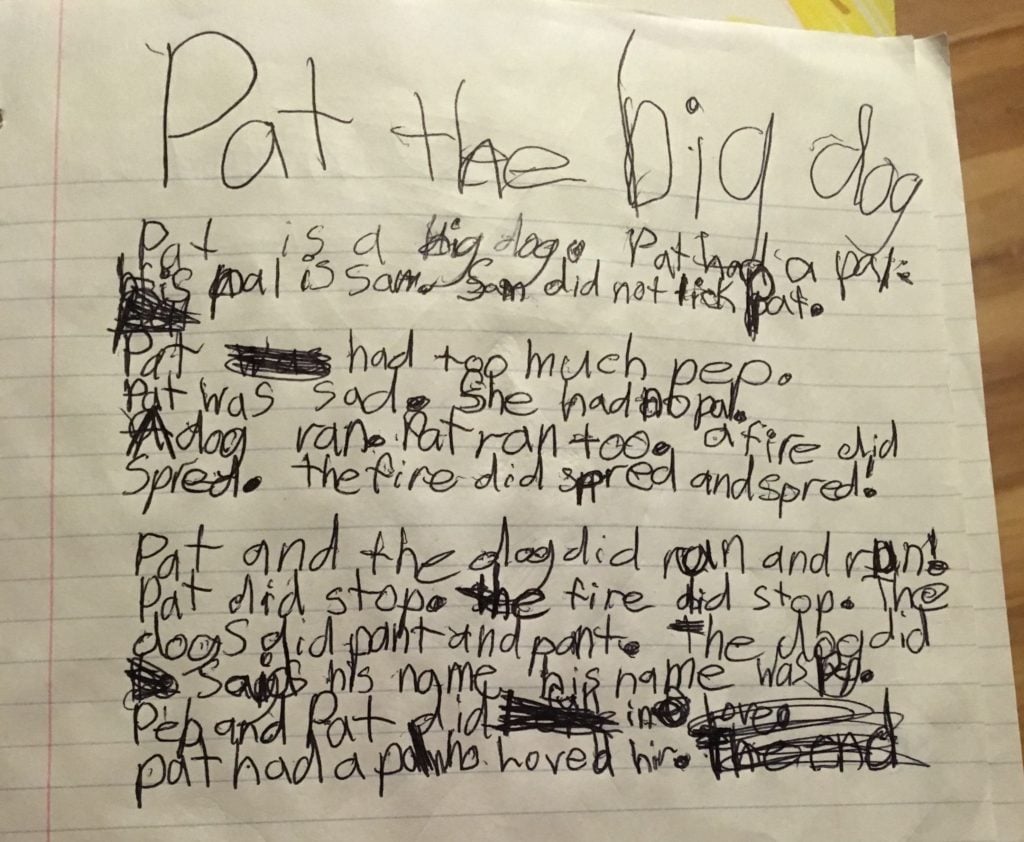

Reading and writing challenges

- Slow and effortful reading

- Difficulty recognizing common sight words (e.g., what, said, come)

- Problems with phonics – connecting letters to sounds

- Trouble sounding out unfamiliar words

- Frequent guessing of words based on shape or context, not actual reading

- Poor spelling, often inconsistent (e.g., spelling the same word differently on the same page)

- Mixing up letters that look similar (e.g., b/d, p/q)

- Skipping words or lines while reading

Writing and language use

- Writing letters backwards or in the wrong order

- Difficulty organizing thoughts into writing (messy handwriting or jumbled sentences)

- Limited vocabulary in writing despite strong verbal skills

- Difficulty learning and using new vocabulary and grammar rules

Memory and learning

- Struggles to remember sequences (e.g., alphabet, days of the week, multiplication tables)

- Trouble remembering instructions or information just heard

- May do better when information is presented visually or hands-on

Speech and listening

- Mispronounces long or unfamiliar words

- Difficulty retrieving the correct word (word-finding issues)

- Might pause a lot in speech or substitute vague words like “thing” or “stuff”

School-related behaviors

- Avoids reading aloud or doing homework

- Complains of headaches or feeling tired when reading

- May appear frustrated or anxious about school

- Shows strong understanding when told something verbally, but not when reading

Strengths often seen

- Strong problem-solving or critical thinking

- Creativity or talent in arts, storytelling, or building things

- Sound verbal reasoning and understanding of complex ideas when explained orally

High school

Dyslexia symptoms in high school can differ from those in younger children and elementary school students. Teens often develop coping strategies, which can mask the challenges. Here are common signs in high school students:

Reading and writing struggles

- Slow or effortful reading (even if the student has good comprehension)

- Difficulty with spelling, especially with common or irregular words

- Trouble reading out loud or misreading words

- Avoidance of reading tasks (e.g., reading aloud in class, reading assignments)

- Frequent grammar or punctuation errors

- Writing that’s disorganized or hard to follow

Language and memory issues

- Difficulty finding the right word when speaking (word retrieval issues)

- Mixing up similar-sounding words

- Poor memory for sequences (like instructions, formulas, steps)

- Difficulty summarizing or paraphrasing information

Academic performance

- Better performance on oral tests than written ones

- Underperformance on timed tests

- Inconsistent grades despite effort

- Struggles in foreign language classes (reading/spelling in another language is even harder)

Emotional and behavioral signs

- Low self-esteem or frustration around schoolwork

- Anxiety about reading or tests

- Avoiding assignments or procrastinating (as a coping mechanism)

- High effort with low output, leading to burnout or apathy

👉 👉 See our detailed guide on dyslexia symptoms.

3. Causes and risk factors

Dyslexia is a neurodevelopmental condition with multiple contributing factors. It is not caused by poor teaching, low intelligence, or lack of motivation. Instead, it arises from a combination of genetic influences, differences in brain structure and function, and underlying cognitive processing weaknesses. Other conditions can also co-occur with dyslexia, adding to the learning challenges.

Genetics and heredity

Dyslexia often runs in families. If a parent or sibling has dyslexia or another language-based learning difficulty, the chances increase significantly that another family member will be affected (Snowling & Melby-Lervåg, 2016).

Research has identified several genes associated with dyslexia, many of which influence brain development and neural connectivity related to language (Paracchini et al., 2007; Scerri & Schulte-Körne, 2010). However, having these genes does not guarantee dyslexia — environmental factors and early language experiences also play a role in shaping outcomes

👉 👉 See our detailed guide on dyslexia and genetics.

Brain differences

Neuroimaging studies have shown that individuals with dyslexia process written language differently. Areas of the brain involved in reading — especially in the left hemisphere — tend to show less activation during reading tasks.

Key brain differences include (Martin et al., 2016; Shaywitz, 2005):

- Underactivation in the left temporo-parietal region, important for decoding words

- Differences in the left occipito-temporal area, involved in recognizing word forms automatically

- Increased reliance on frontal and right hemisphere areas, which are less efficient for reading

These brain patterns are present before reading instruction begins, reinforcing the idea that dyslexia is a biologically based learning difference — not a result of poor schooling.

👉 👉 See our detailed guide on the dyslexic brain.

Cognitive processing weaknesses

Dyslexia is strongly linked to weaknesses in specific cognitive functions that support language and reading development. These weaknesses vary by individual, but the most common are:

| Cognitive Skill | What It Means |

|---|---|

| Phonological processing | Difficulty identifying and manipulating sounds in spoken words (e.g., rhyming, segmenting) |

| Working memory | Trouble holding and using information in mind while performing a task |

| Processing speed | Slower rate of identifying and responding to visual or verbal information |

| Rapid automatic naming | Difficulty quickly naming letters, numbers, or colors — linked to reading fluency |

| Auditory memory | Trouble recalling verbal information just heard |

| Visual sequential memory | Difficulty remembering the order of letters or symbols in words or numbers |

Not all individuals show all of these weaknesses. Some may have only one or two, while others — particularly those with mixed dyslexia — may have multiple cognitive deficits.

Co-occurring conditions

Many individuals with dyslexia also have additional learning or developmental challenges. These co-occurring conditions can make the learning profile more complex and may require additional support.

| Condition | How It Interacts with Dyslexia |

|---|---|

| ADHD | Affects attention, impulse control, and executive function; may mask or worsen reading difficulties |

| Dysgraphia | Impairs handwriting and written expression; often overlaps with spelling difficulties |

| Dyscalculia | Affects numerical reasoning and math skills; can co-occur with language issues |

| Speech and language delays | May contribute to weak phonemic awareness and vocabulary acquisition |

| Anxiety and low self-esteem | Often develop in response to ongoing academic struggles and frustration |

Understanding co-occurring conditions is important for developing a complete support plan that addresses the full range of a child’s needs.

4. Common myths

Despite being well-documented, dyslexia is often misunderstood. Here are some common myths and the truth behind them.

- Myth 1: Dyslexia is a sign of low intelligence. This is one of the most harmful misconceptions. In reality, dyslexia has no connection to intelligence. Many people with dyslexia are highly intelligent and creative, often excelling in problem-solving and thinking outside the box..

- Myth 2: Dyslexia means seeing letters or words backward. While some individuals with dyslexia may reverse letters or numbers, this is not the main symptom. Dyslexia primarily affects how the brain processes written and spoken language, making it difficult to decode words, spell, and read fluently.

- Myth 3: Lazy or unmotivated students are often mislabeled as having dyslexia. This myth ignores the real struggles people with dyslexia face. Dyslexia can make reading and writing very tiring and frustrating, but a lack of effort does not cause it.

- Myth 4: Only boys have dyslexia. This learning disorder affects both boys and girls equally, but boys are more often diagnosed because their reading struggles may be more noticeable or disruptive in classroom settings.

Understanding and addressing these myths is crucial to supporting individuals with dyslexia and ensuring they receive the necessary help to succeed.

5. Diagnosis and testing

Early and accurate diagnosis is key to helping a child with dyslexia reach their full potential. While some children are diagnosed in the early school years, many go undetected until academic struggles become more severe — often around 3rd grade or later.

How is dyslexia diagnosed?

Dyslexia is diagnosed through a comprehensive evaluation that looks at reading, writing, language, and cognitive skills. There is no single test that can “prove” dyslexia — instead, trained professionals gather a variety of data points to build a detailed learning profile.

A diagnosis does not just label the problem — it identifies the child’s specific strengths and weaknesses, allowing intervention to be targeted and effective.

What tests are used?

A comprehensive evaluation includes multiple assessments that examine reading skills, language abilities, and cognitive functioning. These tests help professionals build a detailed picture of how a child processes language — and where they need support. A typical dyslexia assessment might include:

| Test Area | What It Measures |

|---|---|

| Phonological awareness | Ability to hear, identify, and manipulate sounds in words (e.g., rhyming, segmenting) |

| Decoding and word reading | Skill in sounding out unfamiliar words and reading accuracy |

| Reading fluency | Speed and ease of reading connected text and word lists |

| Spelling and writing | Use of phonics, spelling patterns, grammar, and written expression |

| Vocabulary and language | Understanding and use of spoken language; affects comprehension |

| Working memory | Ability to hold and use verbal or visual information temporarily |

| Processing speed | How quickly the brain responds to visual or verbal input |

| Rapid automatic naming | Speed of naming letters, numbers, or colors — linked to fluency |

| Cognitive ability (IQ test) | Measures reasoning, problem-solving, and general intellectual ability; helps rule out intellectual disability |

Including an IQ test helps distinguish dyslexia from other conditions and ensures the reading difficulties are unexpected relative to the child’s overall intellectual potential.

Who initiates the process?

The process can begin in different ways:

- Parents may notice reading struggles and request an evaluation.

- Teachers may raise concerns based on classroom observations and assessments.

- Schools may initiate testing through a psychologist or learning support team.

- Private professionals, such as educational psychologists or speech-language therapists, can conduct evaluations outside the school system.

In many countries, parents can request a psychoeducational evaluation if they suspect a learning disorder — though access and procedures vary.

Why is a thorough assessment important?

A proper diagnosis helps:

- Identify the root cause of a child’s reading difficulties

- Rule out other issues, such as poor vision, hearing problems, or emotional factors

- Create a tailored intervention plan

- Provide access to accommodations, like extra time or assistive tech

- Reduce frustration and build confidence through understanding

Many children with dyslexia are bright, creative, and eager to learn — they simply need the right kind of teaching to unlock their potential.

6. Intervention and prognosis

Effective intervention integrates cognitive training with reading and spelling tutoring based on solid learning principles. Cognitive training is a crucial component, as it aims to strengthen the underlying cognitive skills that underpin reading and language development. Effective intervention also includes structured, evidence-based approaches that target reading, spelling, and writing.

Cognitive training

Here is a breakdown of how cognitive training fits into a dyslexia intervention plan:

What is cognitive training?

Cognitive training involves structured tasks and exercises designed to improve specific mental abilities such as:

- Phonological processing

- Working memory

- Attention and executive function

- Processing speed

- Rapid automatic naming

These are foundational skills that contribute to a child’s ability to learn to read, spell, and write.

How cognitive training helps in dyslexia intervention

- Phonological processing: Many individuals with dyslexia have deficits in phonological awareness (the ability to recognize and manipulate sounds in words). Training that targets phonemic awareness can enhance decoding and spelling skills.

- Working memory: Poor working memory can affect a child’s ability to hold and manipulate sounds and letters while reading. Cognitive exercises designed to improve working memory can indirectly enhance reading fluency.

- Attention and executive function: Sustained attention and mental flexibility are often areas of difficulty for kids with dyslexia. Training that enhances focus, shifting attention, and planning can help children stay on task during reading and writing activities.

- Processing speed: Slow processing can affect fluency and comprehension. Speed-based drills can improve automaticity in recognizing sounds, letters, and high-frequency words.

- Rapid automatic naming: Difficulty quickly naming familiar items like letters, numbers, or colors can slow down word recognition and disrupt reading flow. Training that targets retrieval speed can help improve reading fluency.

Reading, spelling, and writing

Any dyslexia intervention plan should include structured, evidence-based approaches that target reading, spelling, and writing. Here’s a breakdown of key components of effective dyslexia intervention:

Core principles of dyslexia intervention

- Explicit instruction – Skills are taught clearly and directly (not assumed).

- Systematic and sequential – Lessons follow a logical order that builds from simple to complex.

- Multisensory – Engaging visual, auditory, and kinesthetic/tactile pathways to reinforce learning.

- Frequent practice and review – Repetition solidifies skills and promotes retention.

- Individualized and intensive – Tailored to the learner’s specific needs and typically delivered in small groups or one-on-one settings.

Skills targeted

- Decoding (phonics) – Connecting sounds to letters and sounding out words.

- Fluency – Reading with speed, accuracy, and expression.

- Vocabulary – Understanding and using new words.

- Comprehension – Understanding and interpreting what’s read.

- Spelling/writing – Structuring written language accurately.

Hope through intervention

The good news is that dyslexia is treatable — especially when identified early and supported consistently. With the right kind of help, your child can thrive. Early intervention is most effective, but intervention at any age can still be beneficial. Even teens can improve significantly with the proper training.

7. Dyslexia in adults

Dyslexia doesn’t go away in adulthood — it simply looks different. While some adults were diagnosed early, many never received a diagnosis and have spent years developing coping strategies to manage reading and writing challenges.

Common signs include slow or effortful reading, difficulty spelling, frequent word-finding problems, and trouble remembering instructions or names. In the workplace, adults with dyslexia may avoid reading aloud, feel anxious about writing emails or reports, and prefer verbal communication over written.

Despite these challenges, many adults with dyslexia are creative, resilient, and skilled problem-solvers. They may thrive in hands-on fields or roles that emphasize big-picture thinking, collaboration, or visual-spatial reasoning.

With support and self-awareness, adults with dyslexia can continue to grow, succeed, and even turn their learning difference into a strength.

8. Supporting a child with dyslexia

Helping a child with dyslexia thrive requires more than specialized instruction — it takes daily support, patience, and a team effort between school and home. Below are practical strategies that teachers and parents can use to reduce frustration and promote success.

Classroom strategies

| Challenge | What Teachers Can Do |

|---|---|

| Struggles with reading fluency | Allow extra time for reading tasks; provide audiobooks or read-aloud support |

| Trouble decoding new words | Teach phonics explicitly and systematically; offer visual word cards |

| Poor spelling and written expression | Reduce emphasis on spelling in grading; allow typed work and spellcheck tools |

| Difficulty following instructions | Give clear, step-by-step instructions — both verbally and in writing |

| Avoids reading aloud | Let the student preview reading material ahead of time; offer alternatives to oral reading |

| Low confidence in class | Focus on strengths; provide frequent praise for effort, not just results |

| Difficulty with note-taking | Provide printed notes, outlines, or graphic organizers |

Home strategies

| Challenge | What Parents Can Do |

|---|---|

| Homework frustration | Break tasks into small steps; give regular breaks; use timers or checklists |

| Avoidance of reading | Read together daily; let the child choose books on topics they enjoy |

| Slow progress despite effort | Celebrate small wins; remind them that learning takes time and looks different for everyone |

| Trouble remembering facts or instructions | Use visuals, songs, or mnemonics to reinforce memory |

| Emotional ups and downs | Validate their feelings; remind them that dyslexia is a challenge, not a flaw |

| Avoids writing at home | Encourage typing, dictation apps, or drawing ideas before writing |

The power of encouragement

Children with dyslexia often face more daily challenges than their peers — but with consistent encouragement, they can build resilience, confidence, and pride in their progress.

A child who feels supported is more willing to take risks, make mistakes, and keep trying — all of which are essential for learning.

9. Key takeaways

10. Talk to a specialist

If your child is struggling with reading, spelling, or writing, the sooner you act, the better. Dyslexia doesn’t resolve on its own — but with the proper support, your child can overcome these challenges and thrive.

At Edublox, we help children with dyslexia and other learning difficulties develop the foundational cognitive and language skills, and deliver structured reading and spelling instruction based on rigorous, research‑driven methods. Studies show that our approach significantly improves processing speed, memory, and literacy skills, helping students achieve real, measurable gains in the classroom.

Talk to a specialist today to learn how we can help your child reach their potential.

Book a free consultation

References:

- Martin, A., Kronbichler, M., & Richlan, F. (2016). Dyslexic brain activation abnormalities in deep and shallow orthographies: A meta-analysis of 28 functional neuroimaging studies. Human Brain Mapping, 37: 2676–99.

- Paracchini, S., Scerri, T., & Monaco, A. P. (2007). The genetic lexicon of dyslexia. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 8, 57–79.

- Shaywitz, S. (2005). Overcoming dyslexia. New York: Vintage Books.

- Scerri, T. S., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2010). Genetics of developmental dyslexia. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(3), 179–197.

- Snowling, M. J., & Melby-Lervåg, M. (2016). Oral language deficits in familial dyslexia: A meta-analysis and review. Psychological Bulletin, 142(5), 498–545.

Authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyslexia specialist with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities and medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).

Edublox is proud to be a member of the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), a leading organization dedicated to evidence-based research and advocacy for individuals with dyslexia and related learning difficulties.