For decades, reading difficulties like dyslexia have been widely researched, diagnosed, and accommodated in schools worldwide. By contrast, challenges with math—though just as common and often just as debilitating—have long been overlooked.

The term dyscalculia is now recognized internationally, but awareness still lags decades behind dyslexia. This article traces the history of dyscalculia, explores how recognition has evolved, and explains why proper identification matters today.

.

Table of contents:

- Early observations (late 1800s–1950s)

- The term “dyscalculia” (1960s–1980s)

- Slowly growing in recognition (1990s–2010s)

- Neuroscience and modern understanding

- Recognition across the world

- Why recognition matters

- Learn more

1. Early observations (late 1800s–1950s)

The earliest writings on math-specific difficulties emerged not in education, but in neurology. In 1919, German neurologist Salomon Henschen described acalculia—the sudden loss of calculation ability due to brain injury (Ardila & Rosselli, 2002). These cases helped distinguish calculation difficulties from broader intellectual impairments.

By the mid-20th century, psychologists also began noticing children who struggled persistently with arithmetic despite having normal intelligence and no brain injury. Unlike acalculia, these cases were developmental, not acquired. However, such children were often dismissed as careless, lazy, or poorly taught.

2. The term “dyscalculia” (1960s–1980s)

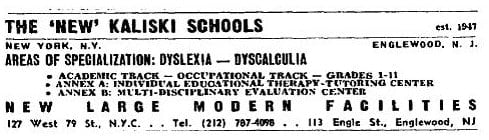

While the earliest medical literature focused on acalculia (math loss after brain injury), the term dyscalculia began to appear in the public sphere earlier than many realize. In May 1968, the New York Times carried an advertisement using the word (see below), demonstrating that math-specific learning problems were being discussed outside of academic circles.

By the 1970s, researchers in Europe—particularly in Sweden—were using the term developmental dyscalculia to describe children with severe, persistent math difficulties. At the time, as with dyslexia, it was viewed as a specific learning disorder in children of average or above-average intelligence: bright in other areas, but unexpectedly poor in mathematics. This early framing reinforced the idea that dyscalculia was not the result of low IQ or poor teaching, but a distinct condition.

3. Slowing growing in recognition (1990s–2010s)

In the 1990s, educational psychologists such as David Geary (1993, 2004) advanced the study of mathematical learning difficulties by identifying different subtypes: some children struggled with basic number sense, others with memory for arithmetic facts, and others with procedural strategies.

Shalev and Gross-Tsur (2001, 2004) conducted epidemiological studies showing that developmental dyscalculia affects approximately 3–6% of the population, similar to rates of dyslexia. This was a turning point: dyscalculia could no longer be dismissed as a rare curiosity.

Despite this, dyscalculia remained underdiagnosed, underfunded, and often misunderstood. Between 2000 and 2010, the US National Institutes of Health allocated $107.2 million to dyslexia research but just $2.3 million to dyscalculia (Butterworth et al., 2011).

4. Neuroscience and modern understanding

The 2000s saw the emergence of brain imaging studies that revealed structural and functional differences in the intraparietal sulcus, a brain region crucial for number processing (Butterworth et al., 2011). These findings strengthened the case for dyscalculia as a genuine, biologically based condition.

At the same time, the definition of learning disabilities was evolving. For decades, both dyslexia and dyscalculia were defined by an IQ-discrepancy model: children were only diagnosed if they struggled in reading or math despite being “bright” in other areas. By the 1990s, some researchers began to question this requirement. The decisive evidence came later, when John Gabrieli and colleagues at MIT showed through brain imaging that poor readers with low IQ and those with average or high IQ shared the same neural markers of dyslexia (Tanaka et al., 2011). This finding overturned the discrepancy model for reading and, by extension, for other learning disorders like dyscalculia.

What matters are not global IQ scores but the cognitive skills that underlie learning. In dyscalculia, research has consistently highlighted deficits in number sense, working memory, visual-spatial processing, and processing speed (Geary, 2004; Szűcs & Goswami, 2013). These skills cut across IQ levels: a child can have strong general reasoning but still lack number sense, or conversely have weaker general reasoning but display the same dyscalculia-related cognitive deficits.

The MIT study helped drive a definitional shift. The DSM-5 (2013) and ICD-11 (2019) both abandoned the IQ-discrepancy requirement, defining specific learning disorders based on persistent academic difficulties despite appropriate instruction. This shift was crucial: children no longer had to “prove” high intelligence to be recognized as having dyscalculia.

5. Recognition across the world

Although dyscalculia is now recognized in diagnostic manuals, its awareness and acceptance vary widely from country to country. Some nations have made progress in policy and teacher training, while others still lag far behind.

United Kingdom

In 2001, the UK’s Department for Education and Skills acknowledged dyscalculia in its report on numeracy difficulties. Later guidance, including the 2009 Rose Review, recommended better teacher awareness. Still, training on dyscalculia remains inconsistent.

United States

In the US, dyscalculia falls under the category of “Specific Learning Disability” in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). However, most schools diagnose dyslexia or reading-based SLDs far more frequently than math-based ones, leaving many children unidentified (Mazzocco & Myers, 2003).

Australia

In Australia, dyscalculia is not formally recognized as a disability category in national education policy, but awareness is slowly increasing. Reports from the Dyslexia–SPELD Foundation and advocacy by researchers such as Brian Butterworth have highlighted the prevalence of math learning difficulties (Butterworth, 2018). Some schools have begun adopting screening tools and interventions, though recognition varies by state and territory.

Advocacy movements

Recent years have seen growing advocacy efforts. For example, Dyscalculia Day is marked each year on March 3 (3/3 symbolizing “math 3”), raising awareness worldwide. Parent groups, nonprofits, and researchers continue to advocate for parity with dyslexia in research, funding, and teacher training.

Despite these efforts, recognition of dyscalculia remains uneven. Without consistent policies, funding, and teacher training, many children worldwide continue to fall through the cracks.

6. Why recognition matters

Dyscalculia is roughly as common as dyslexia but far less recognized. The result is that millions of children grow up believing they are “just bad at math,” when in reality, they have a specific, diagnosable learning disability that requires targeted support.

Lack of recognition can lead to:

- Academic underachievement in mathematics and related subjects

- Emotional impact, such as math anxiety, low self-esteem, and avoidance

- Reduced life opportunities, since numeracy is essential for everyday life, financial independence, and many careers

Raising awareness, training teachers, and ensuring early intervention can change life trajectories.

Dyscalculia today is where dyslexia was 40 years ago—on the verge of broader recognition. The sooner the world acknowledges it, the sooner learners can access the help they deserve.

7. Learn more

- Learn more about the symptoms of dyscalculia — early signs and how they appear at different ages.

- Explore the causes of dyscalculia — what research says about brain, cognitive, and environmental factors.

- Read about dyscalculia treatment and intervention — evidence-based strategies that work.

- See dyscalculia statistics — prevalence, diagnosis rates, and research findings.

- Discover the different types of dyscalculia — how math difficulties can vary by cause and profile.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to help students overcome symptoms of dyscalculia. We work with families across the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond. Book a free consultation to explore how we can support your child’s learning journey.

References for The History and Recognition of Dyscalculia:

- Ardila, A., & Rosselli, M. (2002). Acalculia and dyscalculia. Neuropsychology Review, 12(4), 179–231.

- Butterworth, B. (1999). The mathematical brain. London: Macmillan.

- Butterworth, B. (2018). Dyscalculia: From science to education. Routledge.

- Butterworth, B., Varma, S., & Laurillard, D. (2011). Dyscalculia: From brain to education. Science, 332(6033), 1049–1053.

- Geary, D. C. (1993). Mathematical disabilities: Cognitive, neuropsychological, and genetic components. Psychological Bulletin, 114(2), 345–362.

- Geary, D. C. (2004). Mathematics and learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(1), 4–15.

- Mazzocco, M. M. M., & Myers, G. F. (2003). Complexities in identifying and defining mathematics learning disability in the primary school–age years. Annals of Dyslexia, 53(1), 218–253.

- Shalev, R. S., & Gross-Tsur, V. (2001). Developmental dyscalculia. Pediatric Neurology, 24(5), 337–342.

- Shalev, R. S., Manor, O., & Gross-Tsur, V. (2004). Developmental dyscalculia: A prospective six-year follow-up. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 47(2), 121–125.

- Szűcs, D., & Goswami, U. (2013). Developmental dyscalculia: Fresh perspectives. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 2(2), 33–37.

- Tanaka, H., Black, J. M., Hulme, C., Stanley, L. M., Kesler, S. R., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., … & Gabrieli, J. D. (2011). The brain basis of the phonological deficit in dyslexia is independent of IQ. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1442–1451.

The History and Recognition of Dyscalculia was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyscalculia specialist and with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities.