William is eighteen years old. He shines in drama and art, devours books, and writes poems and short stories in his free time. Yet he cannot graduate with his class—because he hasn’t passed math.

Despite having average intelligence, William has struggled with mathematics since primary school. After years of tutoring, he’s finally able to do basic facts and operations with some confidence. But applying them? That’s a different story. When faced with a test, William grabs numbers from the question and plugs them into formulas he’s memorized—without knowing whether they make sense.

William is not alone.

Table of contents:

- What is dyscalculia?

- What are the types of dyscalculia?

- Three functional subtypes of dyscalculia

- Kosc’s six subtypes of dyscalculia

- The four cognitive subtypes

- Pseudo-dyscalculia

- Why these subtypes matter

- Delve deeper

- Key takeaways

- Talk to a specialist

What is dyscalculia?

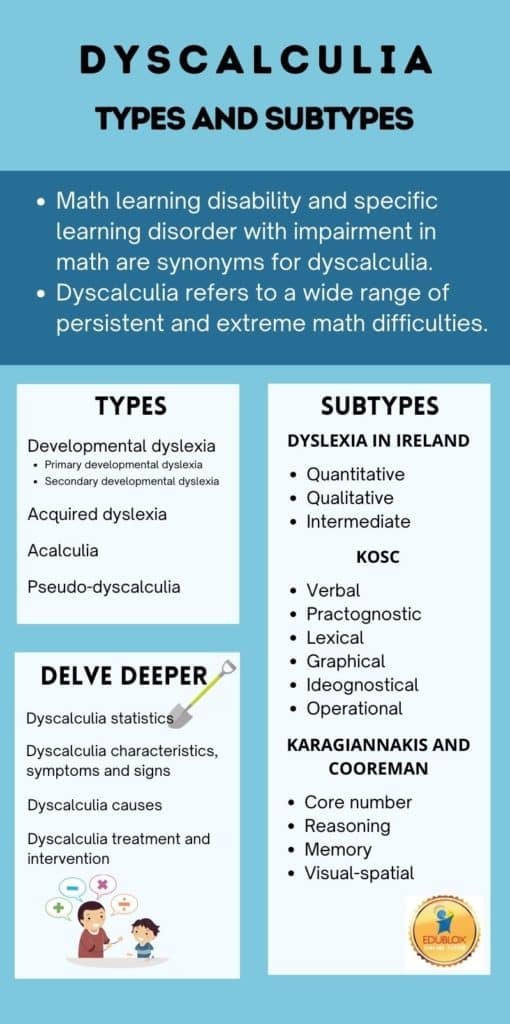

The terms math learning disability and specific learning disorder with impairment in math are synonyms for dyscalculia.

Dyscalculia refers to persistent and severe difficulties with numbers, calculations, and mathematical reasoning. It’s not just “being bad at math.” It’s a specific neurodevelopmental disorder that affects an individual’s ability to process numerical information.

The term comes from the Greek dys (“badly”) and Latin calculare (“to count”), literally meaning “to count badly.” However, dyscalculia encompasses far more than just counting—it involves difficulties with understanding quantity, patterns, procedures, symbols, spatial concepts, and even time.

What are the types of dyscalculia?

There are two broad categories:

- Developmental dyscalculia appears in childhood despite adequate schooling and normal intelligence. It’s not caused by poor teaching, emotional disturbance, or general intellectual disability.

- Acquired dyscalculia (also called acalculia) results from brain injury, such as a stroke or trauma. It affects people who previously had typical mathematical ability.

Some researchers further divide developmental dyscalculia into:

- Primary developmental dyscalculia: A core, biologically based difficulty in understanding numbers or arithmetic.

- Secondary developmental dyscalculia: Mathematical difficulties stemming from broader challenges such as attention deficits, executive dysfunction, or working memory impairments.

In practice, the two often overlap. For example, a child with ADHD may struggle with math due to inattention, while also exhibiting underlying weaknesses in number sense.

Three functional subtypes of dyscalculia

A three-part classification of dyscalculia—quantitative, qualitative, and intermediate—is commonly cited in practitioner discussions and training materials (Nekang, 2016):

- Quantitative dyscalculia: A deficit in counting and calculating. Learners may struggle with basic number sense, estimation, or even reading large numbers.

- Qualitative dyscalculia: Difficulty understanding instructions or applying mathematical operations due to poor mastery of number facts and procedures.

- Intermediate dyscalculia: Inability to work with symbols and numbers, especially when abstract signs (like √, ×, <, >) or large figures are involved. This type often overlaps with conditions like dyspraxia or dyslexia.

These categories highlight the range of difficulties dyscalculic students may face—from basic quantity understanding to abstract symbol manipulation.

Kosc’s six subtypes of dyscalculia

One of the earliest and most influential attempts to classify types of dyscalculia came from Ladislav Kosc, a Czech researcher who, in 1974, defined dyscalculia as a structural disorder of mathematical abilities with a neurological origin. His framework was based on detailed clinical and neuropsychological observation of students with arithmetic difficulties, and it continues to influence how educators and specialists conceptualize different manifestations of math learning disabilities.

Kosc proposed that dyscalculia could be broken down into six distinct subtypes, each associated with different areas of breakdown in mathematical functioning:

- Verbal dyscalculia: This subtype involves difficulties in naming and verbally expressing mathematical terms, quantities, or relationships. A child may understand a numerical quantity when shown a group of objects but be unable to name the correct number aloud. The problem lies not in understanding but in verbal encoding.

- Practognostic dyscalculia: Here, the difficulty lies in connecting numerical ideas to real-world objects. For example, a child may struggle to compare groups of items to determine which has more or less or to manipulate objects when solving basic problems. This subtype reflects a disconnection between perception and quantity handling.

- Lexical dyscalculia: This subtype refers to difficulties in reading and recognizing mathematical symbols, such as digits or operation signs. Students with this subtype may misread symbols (e.g., confusing a “6” with an “8” or “+” with “×”), which interferes with both understanding and solving problems.

- Graphical dyscalculia: This form involves difficulty writing mathematical symbols, numerals, or equations. Students may understand what needs to be written but struggle to produce it accurately. This can be due to motor coordination issues or visual-motor integration weaknesses.

- Ideognostical dyscalculia: This subtype reflects difficulty grasping abstract mathematical concepts and relationships. Children may be able to memorize facts or follow procedures but struggle with understanding the underlying principles (e.g., place value, number lines, or the concept of equality).

- Operational dyscalculia: Even when students understand the symbols and concepts involved, they may still struggle to carry out the steps of arithmetic operations (like borrowing or carrying in subtraction and addition). Operational dyscalculia reflects a breakdown in the ability to perform calculations in a logical and sequential manner.

Kosc’s taxonomy remains significant for its multidimensional view of dyscalculia. Rather than assuming all math difficulties stem from a single cause, his work highlighted the variety of cognitive processes involved in mathematical thinking—and how impairments in one or more of these domains can result in different learning profiles.

The four cognitive subtypes

Building on cognitive and neuropsychological research, Karagiannakis and Cooreman (2015) proposed a model of math learning difficulties (MLD) that identifies four core cognitive domains frequently implicated in dyscalculia:

- Core number sense: Deficits in understanding quantity, magnitude, and basic numerical relationships—skills that typically emerge early in development and form the foundation for later mathematical learning.

- Reasoning: Challenges with logical thinking, problem solving, pattern recognition, and the flexible application of mathematical concepts.

- Memory: Weaknesses in both working memory and long-term memory, particularly in recalling arithmetic facts, procedures, or sequences.

- Visual-spatial processing: Difficulties with visualizing numbers, aligning problems, reading graphs, and understanding spatial or directional concepts in math.

According to this framework, students with dyscalculia may show impairment in one or more of these cognitive domains. This model has practical implications for targeted intervention, suggesting that the type of support provided should align with the student’s cognitive profile rather than a one-size-fits-all program (Karagiannakis & Cooreman, 2015)..

Pseudo-dyscalculia

Not all math struggles stem from cognitive deficits. In pseudo-dyscalculia, students experience such severe math anxiety that it blocks their ability to think or perform calculations. Though they may appear to have a learning disability, the root issue is emotional—often fear, stress, or past negative experiences with math.

These students can often succeed with the right support: confidence-building, stress-reduction techniques, and a non-threatening learning environment. Once the anxiety is addressed, their math skills may improve dramatically.

However, many students with true dyscalculia also develop anxiety over time. When math feels consistently confusing or impossible, fear and frustration are natural. In such cases, anxiety is not the cause, but a consequence, making an already difficult subject even harder.

Distinguishing between anxiety-based and cognitively-based math issues is key—because the interventions are different, and often, both types of support are needed. (Hornigold, 2015).

Why these subtypes matter

Although these subtypes haven’t all been rigorously validated, they highlight an important point: dyscalculia is not a one-size-fits-all condition. It presents differently from student to student—sometimes even from task to task.

Some children struggle to learn the basics, while others master them but struggle to apply them in context. Some do well with abstract algebra but struggle when faced with time, money, or measurements in real life.

Final thoughts

William’s story is not about laziness or lack of intelligence. It’s about a very real, very specific learning disability that affects a surprising number of people—by some estimates, up to 6% of the population.

Understanding the types and subtypes of dyscalculia isn’t just a matter of academic curiosity. It’s the key to helping students like William get the targeted support they need—so they, too, can graduate, succeed, and thrive in the world beyond numbers.

Delve deeper

Want to learn more? Explore the following articles:

🧠 Dyscalculia characteristics, symptoms, and signs

In this article, we explore the characteristics, symptoms, and signs of dyscalculia—what to look for at various ages, how it impacts everyday life, and why early identification is crucial. Recognizing the signs early can make a world of difference.

📊 Dyscalculia statistics

There is no universal definition of dyscalculia, so prevalence estimates vary. Research suggests it affects roughly 6–8% of children—similar to dyslexia—but is far less recognized by parents and educators.

🧬 What causes dyscalculia?

To solve a problem, we must first understand its cause. This section explores genetic influences, brain differences, cognitive deficits, and foundational mathematical skill gaps as potential contributors.

🛠️ Dyscalculia treatment and intervention

Dyscalculia treatment requires more than practice drills. This article outlines five effective, research-backed strategies that help children build foundational skills, reduce anxiety, and overcome math learning barriers.

Key takeways

Talk to a specialist

If you suspect your child may have dyscalculia, do not wait. Getting the right help early can change the trajectory of their academic confidence and future.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyscalculia, including those with mild, moderate, or severe cases. Our programs go beyond traditional tutoring to target the root learning challenges behind math struggles.

We support families across the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond.

Book a free consultation

Let’s talk about your child’s needs — and how we can help.

Dyscalculia Types and Subtypes was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyscalculia specialist with 30+ years’ experience in the learning disabilities field. Medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).

References and sources for Dyscalculia Types and Subtypes:

- Price, G., & Ansari, D. (2013). Dyscalculia: Characteristics, causes, and treatments. Numeracy, 6(1).

- Hornigold, J. (2015). Dyscalculia pocketbook. Alresford, Hampshire: Teachers’ Pocketbooks.

- Karagiannakis, G., & Cooreman, A. (2015). Focused MLD intervention based on the classification of MLD subtypes. In S. Chinn (Ed.), The Routledge International Handbook of Dyscalculia and Mathematical Learning Difficulties (pp. 265–267). Routledge.

- Kaufmann, L., Mazzocco, M. M., Dowker, A., von Aster, M., Göbel, S. M., Grabner, R. H., . . . Nuerk, H.-C. (2013). Dyscalculia from a developmental and differential perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 516.

- Nekang, F. N. (2016). A survey of the mathematical problems (dyscalculia) confronting primary school pupils in Buea Municipality in the South West Region of Cameroon. International Journal of Education and Research, 4(4), 437–452.