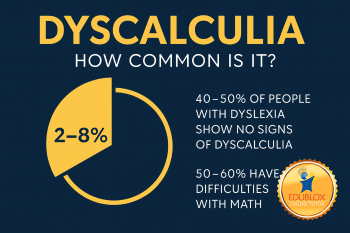

How many people have dyscalculia? The answer sounds simple — somewhere between 2 and 8 percent — but the reality is more complicated. Prevalence rates vary depending on how researchers define dyscalculia, how it is measured, and whether they separate it from general math difficulties.

Definitions matter in statistics

Dyscalculia is often described as a learning disability that affects a person’s ability to understand numbers, learn arithmetic facts, and perform calculations. Some experts distinguish between:

- Developmental dyscalculia, which appears in children and persists into adulthood.

- Acquired dyscalculia (or acalculia) develops after brain injury or disease.

Because definitions differ, prevalence estimates are not uniform. Some researchers use the term broadly to include all persistent math difficulties, while others apply it narrowly to refer only to neurological causes. This lack of consensus results in a wide variation in reported figures.

Reported prevalence rates

Despite definitional differences, most studies place the prevalence of dyscalculia in the same range as dyslexia: around 6–8% of children (Shalev, 2007; Ardila & Rosselli, 2002). This suggests that dyscalculia is as common as reading disabilities, though it receives far less recognition among parents, teachers, and policymakers.

Other researchers report narrower ranges. Badian (1999), for example, found a prevalence of 6.9% in her study: 3.9% of children showed arithmetic difficulties only, while 3% struggled with both arithmetic and reading. She argued that separating these two groups is essential to avoid misleading interpretations.

Some experts suggest even lower figures. Peard (2010) contends that many children included in dyscalculia statistics actually have “learned difficulties” — problems caused by misconceptions, poor instruction, or negative attitudes — rather than an actual neurological disorder. He estimates that the incidence of a genuine, lifelong learning disability in math may be closer to 2%.

Co-occurrence with other conditions

As with other learning disabilities, dyscalculia exists on a spectrum from mild to severe and frequently overlaps with other developmental disorders. Dyslexia and ADHD are the most common co-occurring conditions.

According to the British Dyslexia Association, dyscalculia and dyslexia can occur both independently and together. Research suggests that:

- 40–50% of people with dyslexia show no signs of dyscalculia and perform as well in math as their peers.

- About 10% of people with dyslexia even perform above average in math.

- The remaining 50–60% of people with dyslexia do have difficulties with math.

Best estimates suggest that between 3 and 6 percent of the population has dyscalculia alone — meaning they struggle with math but perform well in other areas of learning.

Why prevalence matters

Whether the figure is closer to 2% or 8%, dyscalculia affects millions of people worldwide. However, awareness lags far behind that of dyslexia, even though the two conditions are equally common. Underrecognition has real consequences: children with dyscalculia may go undiagnosed, misdiagnosed, or unsupported in school, leading to frustration, low self-esteem, and long-term academic struggles.

Understanding prevalence helps educators, parents, and policymakers allocate resources effectively, design targeted interventions, and recognize that math learning disabilities are not rare or isolated cases.

Key takeaway

Most research agrees that between 2 and 8 percent of children have dyscalculia, with a best estimate around 6%. Exact numbers depend on how strictly the condition is defined. What is clear is that dyscalculia is as common as dyslexia — but far less recognized.

Delve deeper

Want to learn more? Explore the following articles:

🧠 Dyscalculia characteristics, symptoms, and signs

In this article, we explore the characteristics, symptoms, and signs of dyscalculia—what to look for at various ages, how it impacts everyday life, and why early identification is crucial. Recognizing the signs early can make a world of difference.

👉 Dyscalculia types and subtypes

Dyscalculia refers to persistent and severe difficulties in learning math. This article explores its types and subtypes, including developmental, acquired, and functional classifications, as well as cognitive and behavioral subtypes proposed by researchers.

🧬 What causes dyscalculia?

To solve a problem, we must first understand its cause. This section explores genetic influences, brain differences, cognitive deficits, and foundational mathematical skill gaps as potential contributors..

🛠️ Dyscalculia treatment and intervention

Dyscalculia treatment requires more than practice drills. This article outlines five effective, research-backed strategies that help children build foundational skills, reduce anxiety, and overcome math learning barriers.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to help students overcome symptoms of dyscalculia. We work with families across the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond. Book a free consultation to explore how we can support your child’s learning journey.

Dyscalculia Statistics and Prevalence: How Common Is It? was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), an educational specialist with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities, and medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).

.

References for Dyscalculia Statistics and Prevalence: How Common Is It?:

- Ardila, A., & Rosselli, M. (2002). Acalculia and dyscalculia. Neuropsychology Review, 12(4), 179–231.

- Badian, N. A. (1999). Persistent arithmetic, reading, or arithmetic and reading disability. Annals of Dyslexia, 49(1), 45–70.

- Peard, R. (2010). Dyscalculia: What is its prevalence? Research evidence from case studies. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 8, 106–113

- Shalev, R. S. (2007). Prevalence of developmental dyscalculia. In D. B. Berch & M. M. M. Mazzocco (Eds.), Why is math so hard for some children? The nature and origins of mathematical learning difficulties and disabilities (pp. 49–60). Brookes Publishing.