The term dyscalculia—from the Greek dys and Latin calculia—means “to count badly” and describes people with severe difficulties with numbers.

Dyscalculia is a specific learning difficulty that hinders students from developing the basic number concepts needed to learn mathematics.

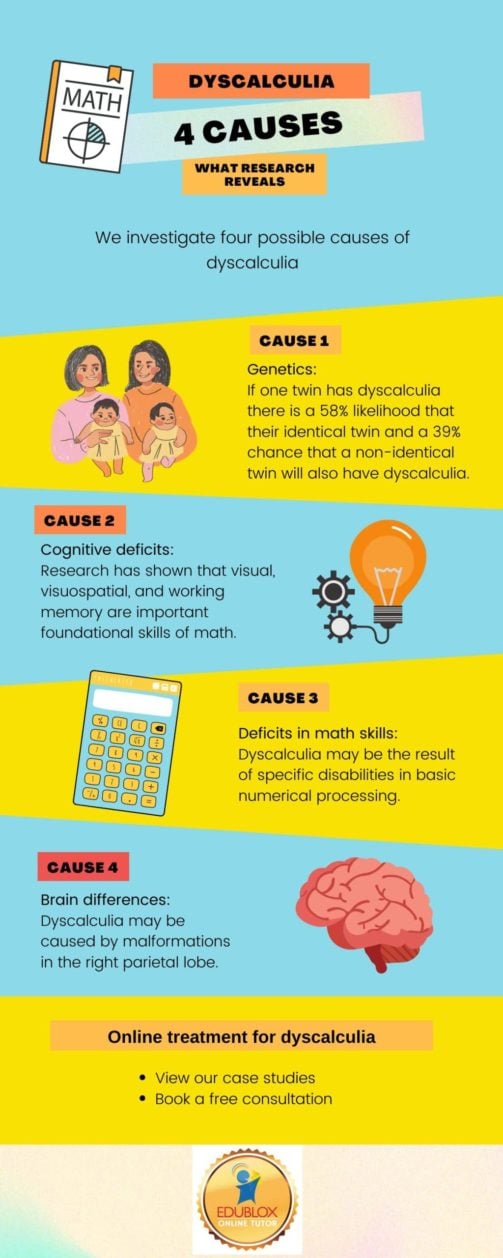

We investigate four possible causes of dyscalculia: genetics, cognitive deficits, gaps in math skills and knowledge, and brain differences. Successful intervention depends on addressing a problem’s cause or causes.

Table of contents:

- Dyscalculia cause no. 1: Genetics

- Dyscalculia cause no. 2: Cognitive deficits

- Dyscalculia cause no. 3: Deficits in math skills

- Dyscalculia cause no. 4: Brain differences

- Dyscalculia case studies

- Delve deeper

- Key takeaways

- Talk to a specialist

Dyscalculia cause no. 1: Genetics

Dyscalculia often runs in families, suggesting that genetic factors contribute to the risk of developing this learning disorder.

If one twin has dyscalculia, there is a 58% likelihood that their identical twin will also have it, and a 39% chance for a non-identical twin.

Similar patterns appear among close relatives. Around half of all first-degree family members of a person with dyscalculia are also affected (mothers: 67%; fathers: 41%; brothers: 53%; sisters: 52%), as well as 43% of second-degree relatives. This prevalence is roughly ten times higher than expected in the general population. There are no significant gender differences (Cohen Kadosh & Walsh, 2007).

Dyscalculia cause no. 2: Cognitive deficits

While some causes of dyscalculia are genetic and others are environmental, cognition mediates the relationship between the brain and behavior. This makes it a practical level of explanation for developing interventions. Understanding the cognitive difficulties that underpin math failure is essential, regardless of whether their origin is constitutional or environmental (Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014).

Research shows that attention; visual and auditory processing; visual, visuospatial, and working memory; and logical thinking are essential foundational skills for mathematics.

Visual and auditory processing

Processing (perceptual) deficits make it difficult to compare similarities and differences, which can affect both reading and math.

Mercer and Pullen (2008) identified three main perceptual problem areas in mathematics: figure-ground differentiation, discrimination, and spatial orientation.

- Figure-ground problems may cause difficulty keeping problems separate. A student may lose their place on a worksheet, confuse problem numbers with digits in the problem, or leave problems unfinished.

- Visual discrimination problems can cause inversions in number recognition, confusion among coins, operation symbols, or the hands of a clock.

- Auditory discrimination problems may lead to confusion in oral counting or in distinguishing similar number words (e.g., fourteen vs. forty).

- Spatial problems can cause reversals, misalignment of numbers, incorrect placement of decimals, difficulty using number lines, and challenges with geometry, time concepts, and directional understanding.

Visual memory

In a study of 171 children (mean age: 10.08 years), Kulp et al. (2001) investigated whether visual perception and memory predict math achievement. Controlling for age and verbal cognitive ability, they found that visual perceptual ability — particularly visual memory — is significantly related to mathematics performance.

Visuospatial memory

Szűcs et al. (2013) compared various theories of dyscalculia in over 1,000 nine-year-old children.

Children with dyscalculia showed poor visuospatial memory, such as remembering item locations in a grid, and were more easily distracted by irrelevant information. For example, when deciding which of two animals is larger in real life, they performed worse if the physically smaller real-life animal appeared larger on-screen.

These findings challenge the idea that dyscalculia always results from a faulty “number sense,” as number sense was intact in this sample.

Working memory

Many studies show that children with mathematical difficulties underperform on working memory tasks. However, others have found no significant differences between children with dyscalculia and typically developing peers (Price & Ansari, 2013).

Dyscalculia cause no. 3: Deficits in math skills

Landerl et al. (2004) concluded that dyscalculia may result from specific disabilities in basic numerical processing rather than from broad cognitive deficits.

In mathematics, there are many skills a student must learn to do, such as counting, adding and subtracting, multiplying and dividing, applying place value, working with fractions, and reading time.

There is also much a student must simply know — terms, definitions, symbols, theorems, and axioms. These are facts rather than procedures. For example, a child who does not know what a sphere is will have to guess when asked, “Which of these twelve objects has the same shape as a sphere?”

How math anxiety contributes to dyscalculia

Mathematics anxiety — hereafter “math anxiety” — is an adverse emotional reaction to math marked by tension, helplessness, mental disorganization, and dread when manipulating numbers or solving problems.

Causes are usually grouped into three categories (Rubinsten & Tannock, 2010):

- Environmental: Negative experiences in math classes or with particular teachers.

- Personal: Low self-esteem, lack of confidence, or the influence of prior negative experiences with math.

- Cognitive: Innate characteristics such as low intelligence or weak math-specific cognitive abilities.

Math anxiety may influence course choices in school and career paths. It can be specific (triggered by certain math situations) or global (a general aversion to all math). Extreme cases may lead to a phobia of mathematics or math-related devices.

Math anxiety is distinct from general anxiety; it can occur even in the absence of other anxiety traits. It directly interferes with underlying cognitive processes during math tasks, especially for individuals with dyscalculia, who may experience intense fear that impedes learning math concepts, skills, and test performance (Rubinsten & Tannock, 2010).

Franklin (2018) notes that children with dyscalculia are more prone to math anxiety than their peers. This creates a catch-22: avoiding math activities leads to falling further behind, which increases anxiety, which further reduces engagement — a self-reinforcing cycle.

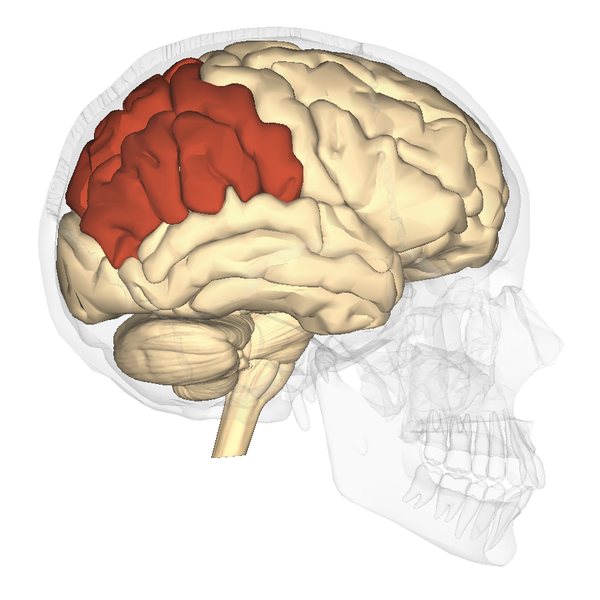

Dyscalculia cause no. 4: Brain differences

Cohen Kadosh et al. (2007) found strong evidence that dyscalculia can be linked to malformations in the right parietal lobe.

Using neuronavigated transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), they temporarily induced dyscalculia-like behavior in people without the condition. Participants completed a math task comparing two digits — one larger in physical size, the other larger numerically. For example, comparing a 2 and a 4, where the 2 was in a larger font. They had to decide which number was numerically larger.

The TMS effect lasted only a few hundred milliseconds and was applied just at the moment participants evaluated the numbers. The test measured automatic number processing in both dyscalculic and non-dyscalculic individuals.

The researchers found that non-dyscalculic participants displayed dyscalculia-like behavior only during TMS disruptions to the right intraparietal sulcus. This was later confirmed in participants with developmental dyscalculia, whose results matched the TMS-induced behavior of the non-dyscalculic group — but not after left parietal TMS or sham stimulation.

McCaskey et al. (2020) also concluded that dyscalculia is associated with reduced gray and white matter volumes in number-related brain areas.

Brain differences are not brain disorders

As Protopapas and Parrila (2018) note, differences in brain structure or activity are expected whenever there are differences in behavior, ability, or performance. Such differences do not, in themselves, indicate abnormality — they simply reflect the neural basis of the behavioral differences.

The brain’s ability to adapt

Importantly, the brain is plastic. New neural connections can form, and the internal structure of existing synapses can change. New neurons — particularly in learning and memory centers — are generated at an estimated rate of about 700 per day (Spalding, 2015). Neurons also die each day, keeping the overall number fairly stable, with a gradual decline as we age.

When a person develops expertise in a specific skill, the brain regions involved in that skill can grow. This adaptability means that, with the right interventions, people can overcome learning obstacles such as dyscalculia, despite genetic influences or structural differences.

Dyscalculia case studies

Real-life experiences demonstrate how addressing the underlying causes of dyscalculia can transform learning outcomes. The following Edublox case studies illustrate the impact of targeted intervention.

Hannah’s story

Six years of teaching and tutoring had failed to help Hannah, who had severe dyscalculia. Her mother, Robyn — a family physician — discovered the Edublox system and decided to give it a try. In a video testimonial, Robyn explains how the program transformed her daughter’s learning and confidence. She volunteered to share her story because, in her words, “Edublox has changed my daughter’s life.”

Amy’s story

Sandy shares a similar experience with her daughter, Amy, who was diagnosed with both dyscalculia and dyslexia. In her video, Sandy describes how Edublox helped fill in the gaps Amy was missing — from working memory and number sense to understanding price tags and applying math in everyday situations.

Veronica’s story

Veronica struggled with both reading and mathematics due to dyspraxia. Her father recounts how the Edublox math program helped her gain confidence, develop critical skills, and approach learning in a way that finally made sense.

Delve deeper

Want to learn more? Explore the following articles:

📊 Dyscalculia statistics

There is no universal definition of dyscalculia, so prevalence estimates vary. Research suggests it affects roughly 6–8% of children—similar to dyslexia—but is far less recognized by parents and educators.

🧠 Dyscalculia characteristics, symptoms, and signs

In this article, we explore the characteristics, symptoms, and signs of dyscalculia—what to look for at various ages, how it impacts everyday life, and why early identification is crucial. Recognizing the signs early can make a world of difference.

👉 Dyscalculia types and subtypes

Dyscalculia refers to persistent and severe difficulties in learning math. This article explores its types and subtypes, including developmental, acquired, and functional classifications, as well as cognitive and behavioral subtypes proposed by researchers.

🛠️ Dyscalculia treatment and intervention

Dyscalculia treatment requires more than practice drills. This article outlines five effective, research-backed strategies that help children build foundational skills, reduce anxiety, and overcome math learning barriers.

Key takeaways

Talk to a specialist

If you suspect your child may have dyscalculia, do not wait. Getting the right help early can change the trajectory of their academic confidence and future.

Edublox offers cognitive training and live online tutoring to students with dyscalculia, including those with mild, moderate, or severe cases. Our programs go beyond traditional tutoring to target the root learning challenges behind math struggles.

We support families across the United States, Canada, Australia, and beyond.

Book a free consultation

Let’s talk about your child’s needs — and how we can help.

4 Causes of Dyscalculia was authored by Sue du Plessis (B.A. Hons Psychology; B.D.), a dyscalculia specialist and with 30+ years of experience in learning disabilities and medically reviewed by Dr. Zelda Strydom (MBChB).

References for 4 Causes of Dyscalculia:

- Cohen Kadosh, R., & Walsh, V. (2007). Dyscalculia. Current Biology, 17(22), R946–R947.

- Cohen Kadosh, R., Cohen Kadosh, K., Schuhmann, T., Kaas, A., Goebel, R., Henik, A., & Sack, A. T. (2007). Virtual dyscalculia induced by parietal-lobe TMS impairs automatic magnitude processing. Current Biology, 17(8), 689–693.

- Elliott, J. G., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2014). The dyslexia debate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Franklin, D. (2018). Helping your child with language-based learning disabilities: Strategies to succeed in school and life with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, ADHD, and processing disorders. TarcherPerigee.

- Kulp, M. T., Earley, M. J., Mitchell, G., Edwards, K. E., Timmerman, L. M., Frasco, C. S., & Geiger, M. (2001). Are visual perceptual skills related to mathematics ability in second through sixth grade children? Focus on Learning Problems in Mathematics, 26(4), 44–54.

- Landerl, K., Bevan, A., & Butterworth, B. (2004). Developmental dyscalculia and basic numerical capacities: A study of 8–9-year-old students. Cognition, 93(2), 99–125.

- McCaskey, U., von Aster, M., O’Gorman, R., & Kucian, K. (2020). Persistent differences in brain structure in developmental dyscalculia: A longitudinal morphometry study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 272.

- Mercer, C. D., & Pullen, P. C. (2008). Students with learning disabilities (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Price, G., & Ansari, D. (2013). Dyscalculia: Characteristics, causes, and treatments. Numeracy, 6(1).

- Protopapas, A., & Parrila, R. (2018). Is dyslexia a brain disorder? Brain Sciences, 8(4), 61.

- Spalding, K. L., Bergmann, O., Alkass, K., Bernard, S., Salehpour, M., Huttner, H. B., Boström, E., Westerlund, I., Vial, C., Buchholz, B. A., Possnert, G., Mash, D. C., Druid, H., & Frisén, J. (2013). Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell, 153(6), 1219–1227.

- Szűcs, D., Devine, A., Soltesz, F., Nobes, A., & Gabriel, F. (2013). Developmental dyscalculia is related to visuo-spatial memory and inhibition impairment. Cortex, 49(10), 2674–2688.

- Rubinsten, O., & Tannock, R. (2010). Mathematics anxiety in children with developmental dyscalculia. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 6, 46.