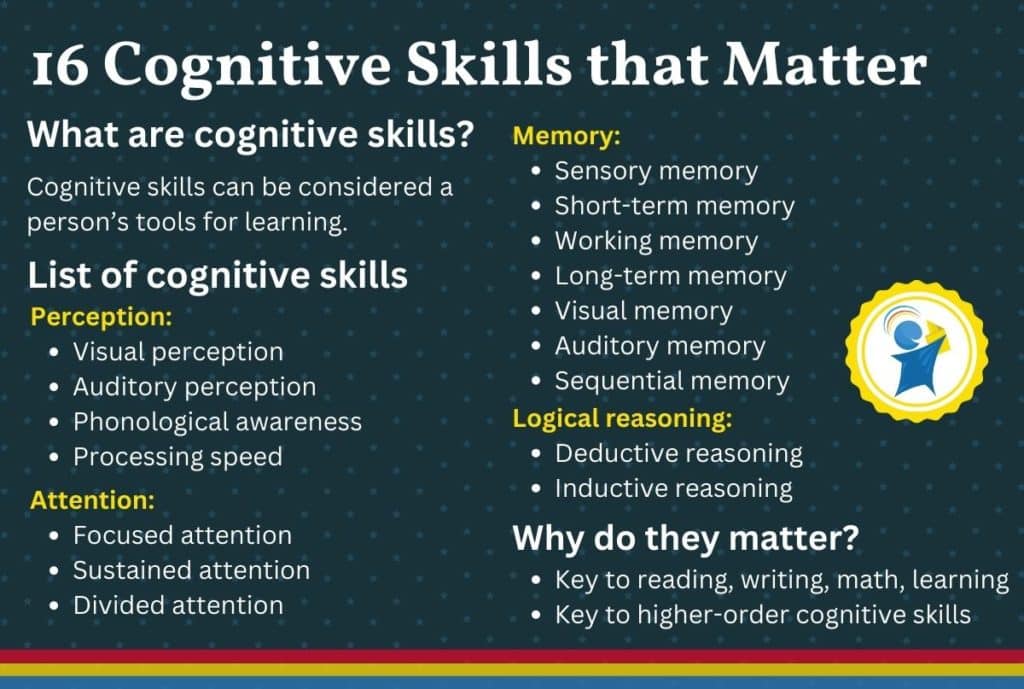

Cognitive skills are mental skills used in acquiring knowledge, manipulating information, reasoning, and problem-solving. Synonyms are cognitive abilities, cognitive functions, or cognitive capabilities.

Cognitive skills can be considered a person’s tools for learning. With the right tools, one can complete tasks with ease and efficiency. Imagine, for example, trying to mix cement with a spoon rather than a cement mixer. Imagine trying to mow the lawn with a pair of scissors!

One of the most common complaints among educators is that their students lack the cognitive or brain-based abilities to handle a curriculum. Although this is anecdotal at best, teaching cognitive skills is overlooked at all levels of education.

Table of contents:

List of core cognitive skills

The word core refers to the central, most essential part of anything. In the same way, core cognitive skills are the foundational brain-based abilities that make learning possible. Without them, academic progress is likely to stall—no matter how good the teaching or curriculum. These core skills include perception, attention, memory, and logical reasoning.

– Perception

Imagine looking at a red apple. Your eyes receive light waves reflected from its surface—this is sensation. But recognizing it as an apple, understanding its shape, and associating it with the word red or fruit—that’s perception.

Sensation is the raw input of information by our sensory receptors—for example, the eyes, ears, skin, nostrils, and tongue. In vision, sensation occurs when rays of light are collected by the eye and focused on the retina. In hearing, sensation occurs as waves of pulsating air are collected by the outer ear and transmitted through the bones of the middle ear to the cochlear nerve.

Perception, also called processing, is the brain’s interpretation of what is sensed. For example, the light striking the retina may be interpreted as a particular color, pattern, or shape. Similarly, sounds collected by the ears may be interpreted as music, a human voice, or background noise. In essence, perception means interpretation.

- Visual perception is the cognitive component of interpreting visual stimuli. Simply put, it is what the brain does with what the eyes see.

- Auditory perception is the ability to identify, interpret, and assign meaning to sound—it is what the brain does with what the ears hear.

- A related skill is phonological awareness, particularly phonemic awareness—the ability to hear and manipulate the individual sounds (phonemes) in words. This auditory skill is at the heart of learning to read.

- Another essential aspect is processing speed, which refers to the time it takes to perceive information, interpret it, and formulate or enact a response. In simpler terms, it’s how long it takes to get things done. A slower processing speed can make even routine tasks feel overwhelming or laborious.

Perception is shaped not only by the senses but also by experience. A lack of experience may cause a person to misinterpret what they have seen or heard. In other words, perception represents our apprehension of the present through the lens of past experience—or, as philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote in Critique of Pure Reason (1781):

“We see things not as they are but as we are.”

– Attention

Perception depends on attention. Attention is what allows us to focus deliberately on certain stimuli while ignoring others. We don’t—and can’t—notice everything in our environment. Instead, we choose (sometimes consciously, sometimes not) what to pay attention to and what to tune out.

This mental filter prevents us from being overwhelmed by the complexity of the world around us. In doing so, attention plays a central role in how we perceive, remember, and learn.

The psychologist William James (1842–1910) recognized the power of attention more than a century ago. In Psychology: The Briefer Course, he wrote:

“A thing may be present to a man a hundred times, but if he persistently fails to notice it, it cannot be said to enter his experience.”

Attention can be divided into three main types:

- Focused attention is the ability to concentrate on one specific stimulus while ignoring distractions. A child reading a book in a noisy room relies on this skill.

- Sustained attention is the capacity to maintain focus over time—for example, during a full class period or while completing a multi-step task.

- Divided attention is the ability to split focus between two or more tasks at once, such as taking notes while listening to a lecture.

– Memory

Memory is the mental process by which information is encoded, stored, and later retrieved. Although we often speak of “memory” as if it were a single ability, it’s actually a set of distinct but related systems. Each type plays a unique role in learning.

Depending on how long information is stored, memory can be divided into four major categories:

- Sensory memory holds impressions of sensory input for a very brief time—just long enough for the brain to decide whether to process it further. For example, when you glance at a word and still see it in your mind for a split second afterward, that’s iconic memory, a type of sensory memory.

- Iconic memory stores what we see

- Echoic memory stores what we hear

- Haptic memory stores what we feel

.

- Short-term memory holds small amounts of information for a few seconds—such as a phone number you’re about to dial. It’s fragile and easily lost unless actively rehearsed.

- Working memory goes a step further: it allows us to hold and manipulate information. Like a mental workspace, it helps us follow multi-step instructions, solve problems, and keep track of our thoughts. For example, solving (3 × 3) + (4 × 2) in your head requires holding both intermediate results—9 and 8—in working memory to reach the final answer.

- Long-term memory stores information more permanently, from basic facts to motor skills like riding a bicycle. Some of this information we can recall deliberately; other memories influence us without conscious awareness.

When it comes to memory, one’s senses are involved too.

- Visual memory involves the brain’s ability to store and retrieve previously experienced visual sensations and perceptions when the original stimuli are no longer present. Various researchers have stated that as much as 80 percent of all learning occurs through the eye, with visual memory being a crucial aspect.

- Auditory memory involves taking in information that is presented orally, processing that information, storing it in one’s mind, and then recalling what one has heard. Basically, it involves the skills of attending, listening, processing, storing, and recalling.

- Sequential memory requires one to recall items in a specific order. For example, the order of the elements is paramount in counting and saying the days of the week, months of the year, a telephone number, and the alphabet. Visual sequential memory is the ability to remember things seen in sequence, while auditory sequential memory is the ability to remember things heard in order..

– Logical reasoning

Logical reasoning is the process of reaching a conclusion through a rational, step-by-step approach based on known facts or observations. It underpins our ability to make sense of information, solve problems, and draw sound conclusions.

- Deductive reasoning begins with a broad truth (the major premise), such as the statement that all men are mortal. This is followed by the minor premise, a more specific statement, such as that Socrates is a man. A conclusion follows: Socrates is mortal. The conclusion cannot be false if both the major and minor premises are true.

- In inductive reasoning, broad conclusions are drawn from specific observations; data leads to conclusions. If the data shows a tangible pattern, it will support a hypothesis. For example, having seen ten white swans, we could use inductive reasoning to conclude that all swans are white.

Of course, this hypothesis is easier to disprove than prove, and premises are not necessarily true, but true given the existing evidence and that one cannot find a situation in which it is not.

Why do cognitive skills matter?

Many studies over many decades have shown that cognitive skills — perception, attention, memory, and logical reasoning — determine an individual’s learning ability; according to Oxfordlearning.com, they are the skills that “separate the good learners from the so-so learners.” In essence, when cognitive skills are strong, learning is fast and easy. Conversely, when cognitive skills are weak, learning becomes a challenge.

Since cognitive abilities are crucial to reading, writing, math, and learning, they are typically impaired in developmental disorders of attention, language, reading, and mathematics, such as ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia.

– Key to reading, writing, math, and learning

- A study by Cheng et al. (2018) suggests that visual perception deficits commonly underlie developmental dyslexia and dyscalculia.

. - Phonological processing skills play an essential role in the development of reading. For example, Bradley and Bryant (1983) found high correlations between preschool children’s initial rhyme awareness and their reading and spelling development over three years. This link held even after controlling for other variables, such as IQ and memory.

. - Multiple research studies have linked difficulties in processing speed with ADHD and reading disorders. Stenneken et al. (2011) compared a group of high-achieving young adults with dyslexia to a matched group of typical readers. The dyslexic group showed a striking reduction in processing speed (26% compared to controls) while their working memory storage capacity was in the normal range.

.

- Thirty-six 9‐year‐old children took a test of image persistence in visual sensory (iconic) memory and the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability. The reading test gives scores for fluency, accuracy, and comprehension. All three measures of reading performance were significantly related to icon persistence (Riding & Pugh, 1977).

. - Kulp et al. (2002) investigated the relationship between visual memory and academics in 155 second- through fourth-grade children; Optometry and Vision Science published the results. The researchers concluded that poor visual memory ability is significantly related to below-average reading decoding, math, and overall academic achievement as measured by the Stanford Achievement Test.

. - Research has confirmed that auditory recall plays a crucial role in literacy and directly impacts reading, spelling, writing, and math skills. Children with poor auditory memory skills may struggle to recognize sounds and match them to letters – a common symptom of a reading disability or dyslexia. Research by Plaza et al. (2002) found that dyslexic children exhibited a significant deficit in tasks involving auditory memory skills (digit span, unfamiliar word repetition, sentence repetition) compared with their age-mates.

. - Guthrie et al. (1972) investigated relationships between visual sequential recall and reading in 81 typical and 43 disabled readers. The researchers identified significant, positive associations between visual sequential memory and paragraph comprehension, oral reading, and word recognition.

. - Howes et al. (1999) compared 24 readers with auditory dyslexia and 21 with visual dyslexia to 90 control group participants. The researchers revealed auditory sequential memory impairments for both types of readers with dyslexia and multiple strengths for good readers.

. - Working memory is a cornerstone for learning of all kinds, from reading and note-taking to math calculations. Weiss and colleagues (2014) tested 52 musicians, 24 with dyslexia and 28 without dyslexia, and compared two groups’ performances on various auditory tests. On most auditory processing tests, the dyslexic musicians scored as well as their nondyslexic counterparts and even better than the general population. Where they performed much worse was on tests of auditory working memory. The dyslexic musicians with the poorest working memory tended to have the lowest reading accuracy.

. - A study by Bhat (2016) examined the contribution of six components of reasoning ability (inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning, linear reasoning, conditional reasoning, cause-and-effect reasoning, and analogical reasoning) to explain the variation in the academic achievement of 598 class 10th students. The predictive power of various components of reasoning ability for academic achievement was 31.5%. Out of the six dimensions of reasoning ability, the maximum involvement was reflected by deductive reasoning (with a reliability coefficient of .49), followed by cause and effect reasoning (.26), inductive reasoning (.16), linear reasoning (.05), conditional reasoning (.03) and analogical reasoning (.02) on academic achievement..

Each cognitive skill plays a part in processing new information. That means if even one of these skills is weak, no matter what kind of information is coming one’s way, grasping, retaining, or using that information is impacted.

Most learning challenges are the result of weak cognitive skills. But more importantly, our core cognitive abilities are crucial to developing higher-order cognitive functions.

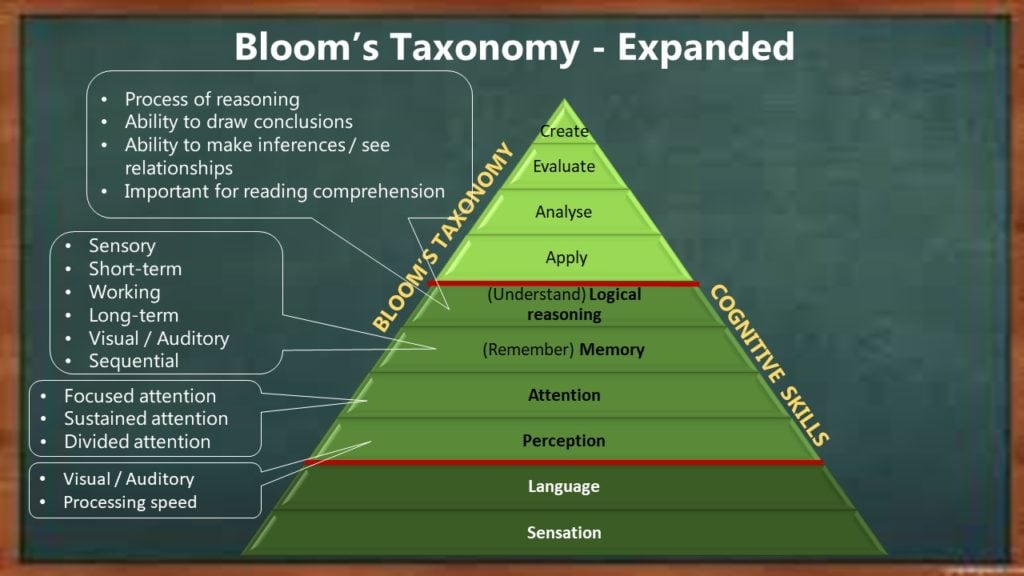

– Key to higher-order cognitive skills

Learning does not take place on a single level but is a stratified process. For example, one has to learn to count before it becomes possible to learn to add and subtract. Suppose one tried to teach a child who had not yet learned to count to add or subtract. That would be impossible, and no amount of effort would ever succeed in teaching the child to add and subtract. This shows that counting is a skill that needs to be mastered before it becomes possible to learn to do calculations. In the same way, core, lower-level cognitive abilities must be acquired first, before it becomes possible to master higher-order brain-based skills.

Higher-order cognitive skills — also called higher-order thinking skills — are complex cognitive skills that go beyond basic observation of facts and memorization. They are what we are talking about when we want our students to be evaluative, creative, and innovative. According to Paul and Elder (2007), much of our thinking — left to itself — is biased, distorted, partial, uninformed, or downright prejudiced. Yet, the quality of our life and what we will produce, make, or build depends precisely on the quality of our thought. Critical thinking is the ability to think in an organized and rational manner to understand connections between ideas and facts. It helps you decide what to believe. In other words, it’s “thinking about thinking” — identifying, analyzing, and then fixing flaws in our thinking. Critical thinking is the foundation of a good education.

Bloom’s taxonomy is an educational model that describes the cognitive processes of learning and developing mastery of subjects. Named after Benjamin Bloom, head of a committee of researchers and educators, this model was developed in the 1950s and 60s. Bloom’s taxonomy and critical thinking go hand in hand. Bloom’s taxonomy takes students through a thought process of analyzing information or knowledge critically. The goal is to encourage higher-order thought in students by building up from lower-level cognitive abilities.

Below is an expanded version of the well-known Bloom’s taxonomy, in which we have included the core cognitive skills:

How can cognitive skills be improved?

Edublox specializes in educational interventions that make children smarter, help them learn and read faster, and do math with ease. Our programs enable learners to overcome reading difficulties and other learning obstacles, assisting them to become life-long learners and empowering them to realize their highest educational goals.

Edublox is grounded in pedagogical research and 30+ years of experience demonstrating that weak underlying cognitive skills account for most learning difficulties. Underlying cognitive skills include perception, attention, memory, and logical reasoning. Specific cognitive exercises can strengthen these weaknesses leading to increased performance in reading, spelling, writing, math, and learning.

- Edublox presented a one-week program in Singapore to 27 students, ages 10 to 12; the control group comprised 25 students. The results of the study showed a significant improvement in focused attention.

. - Results of a research study show that Edublox Online Tutor improves processing speed; the auditory memory of the Edublox group also improved significantly according to the paired samples t-test.

. - A study by Mays (2014) found a significant improvement in visual memory – from 6.2 to 7.5 years following an intensive one-week Edublox program of 22.5 hours. .

Edublox Online Tutor has been optimized for children aged 7 to 13, is suitable for the gifted and less gifted, and can be used at home and school. Our programs are effective in alleviating a variety of symptoms associated with dyslexia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia. Book a free consultation to discuss you child’s learning needs..

Key takeaways

James, W. (1892). Psychology: Briefer Course. New York: Henry Holt and Company, p. 261.